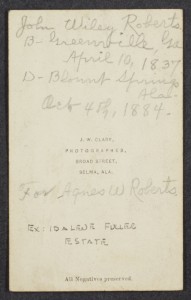

Throughout the late nineteenth century, photographers treated the backing of cartes-de-visite as advertising for potential customers. Many studios included elaborate descriptions of their services and listed location information so that the recipients of the carte-de-visite knew where to get their own photos taken. Concerned more with growing their businesses than with recording the moment for posterity, studios and galleries rarely included when the cartes-de-visite was actually taken. As a result, many of the collection's images are either undated or list dates or estimates provided by customers, recipients, or contemporary archivists.

While the dates recorded by customers, recipients, and archivists provide a relatively reliable chronological record, the estimates, determined as part of this project, pose challenges. Using city directories, prosopographies, and local histories, project members determined when photographers in larger cities like Baltimore, New Orleans, and Louisville worked at specific addresses. William F. Shorey, for instance, operated in Baltimore, Maryland between 1864 and 1890. Based on city directories, Shorey moved his studio in 1867, 1879, and 1888. Using the location information on the photograph's backing, we determined approximate ranges for when the photographs were taken. While this process only creates a narrower span, the estimates help fill in the gaps concerning the spread of southern photography.

Despite the progress brought about by these efforts, only 609 and of the 3356 cartes-de-visite possess either dates or estimates. Although this represents less than one-fifth of the collection, the sample roughly corresponds to the rise and fall of cartes-de-visite in the South. In the early 1850s, southern photography grew steadily through the sale of daguerreotypes, tintypes and ambrotypes. After the Panic of 1857 shuttered many studios and galleries, inexpensive albumen prints, and in particular cartes-de-visite, allowed the remaining photographers to expand their businesses and without the expensive materials and processes necessary for daguerreotypes and other, earlier kinds of photography (Jeffrey Ruggles, Photography in Virginia (Richmond: Virginia Historical Society, 2008), 25). As the cartes-de-visite grew in popularity, the inexpensive format became an accessible memento for a wide range of people. During the Civil War, soldiers took advantage of cartes-de-visite to send photographs to their families and loved ones. Cartes-de-visite also became an important part of wartime propaganda, with both the Confederacy and the Union circulating portraits of generals and leaders (Ruggles, 49).

Photographic formats remained largely the same throughout the 1860s and 1870s. As the South recovered from wartime devastation, cartes-de-visite remained popular and the prints dropped in price as materials became easier to produce (Ruggles, 63). By the 1880s and 1890s, however, the cabinet card, a larger, higher quality albumen print, challenged and eventually surpassed the carte-de-visite in popularity. By the twentieth century, newer photographic technologies replaced both the carte-de-visite and the cabinet card and the formats disappeared from use. Spanning from 1851 to 1896, the Southern Cartes-de-Visite Collection reflects the explosion of the format in the South and its gradual decline.