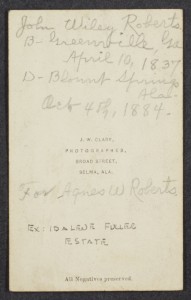

The location data collected on the cartes-de-visite provides an extraordinarily valuable resource to researchers. Due to how the photographs were advertised and sold, studios listed their address or general location on the back of the carte-de-visite and often left out information such as the specific photographer, the subject, or the year the photograph was taken. As a result, the location information was recorded on the day the photograph was taken, while many other details were later written on the backing by the customer, by archivists and collectors, or lost altogether.

The consistent inclusion of location information provided by studios and their photographers lends itself to geospatial analysis. Developed in France in the early 1850s, cartes-de-visite were originally handed out to friends and family as calling cards during visits (Jeffrey Ruggles, Photography in Virginia (Richmond: Virginia Historical Society, 2008), 26). Studios and galleries commonly sold the small photographs by the dozen, allowing customers to have a supply of prints for their social circle. Photographers took advantage of the format and included what amounted to small advertisements on the backing, letting the recipient know where they could also obtain cartes-de-visite. Distributed through personal networks, cartes-de-visite allowed studios to announce their location to a receptive audience.

The A.S. Williams III Americana Collection is home to 3,356 cartes-de-visite, 3,311 of which include a location. These range from the names of small towns, where studios would have been easily found, to specific addresses in larger cities like Baltimore, New Orleans, or Richmond. Both the location map and the state map above, reveal how photography spread through the South in accordance with the region's settlement and growth. The older, former Chesapeake colonies of Virginia and Maryland dominate the collection. Settled earlier and more densely than their more southern counterparts, these two states granted photographers more opportunity to establish themselves in cities and smaller towns. This is especially evident in Virginia, where photographers lined the Shenandoah Valley and opened studios in towns like Staunton, Harrisonburg, and Roanaoke. In contrast, photographers in states like Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi occasionally found themselves relocating to new towns and states in search of new business.

In larger southern cities, the collection reveals how photographic studios clustered on specific streets or commercial districts. In Baltimore, for instance, studios lined West Baltimore Street, while photographers in Louisville populated Market Street, Main Street, and nearby blocks. Using the collection, scholars can not only understand how photography spread across the southern states, but also explore the prominence of these institutions in local cities and towns.