Mary Elizabeth Phillips at Lincoln, 1896-1927

Arguably the most important figure in the history of the Lincoln Normal School, Principal Mary Elizabeth Phillips helped to transform the school during the early decades of the twentieth century. Though she arrived at Lincoln as the school’s sixth principal, after it had been open for nearly 30 years, her influence on the institution was foundational.

Principal Phillips in her room at Lincoln Normal

When Phillips arrived at Lincoln Normal in 1896, the school was faltering, and its 150 students attended classes in two buildings: an old plantation house and a one-room primary school building next to the Congregational Church. Phillips had been recruited from teaching at Talladega College, another AMA school in Alabama, to help turn Lincoln Normal around. But Lincoln Normal was deeply in debt and among the most poorly-funded AMA institutions. By 1897 the AMA announced that to focus its resources on more successful schools, it planned to close Lincoln Normal. In response to this news, local residents, teachers, and students pledged $1,400 in funds to cover the school’s debts. To further cut costs, teachers agreed to go a year without salary, and parents offered to supply provisions for the instructors’ meals. The AMA rewarded to this commitment by buying new land for the school’s expansion and allocating matching financial support.

Phillips and teachers in an improvised sled during the snowstorm of 1913

Phillips oversaw significant changes in her tenure at Lincoln Normal. In the early years of the twentieth century, several new buildings were added to the campus, and by late in Phillips’ career, the school population had grown to nearly 600. In 1904, she used an inheritance from her father’s estate to improve the front of the Patterson Home, which became known as Phillips Hall. In her final years, she is said to have repeated that she planned to retire from her work on the day that she could no longer help Lincoln Normal to grow and improve. This day never came, as Phillips continued to serve the institution within weeks of her death in 1927. On the Sunday following her death, alumni met on the campus to plan a memorial for the administrator. The Phillips Memorial Auditorium, a free-standing auditorium such as Phillips had long hoped that the school would have, was completed and dedicated in the spring of 1939. Apart from the Gymnasium and a single classroom building, it is the only school building that remains standing today, and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1990.

Phillips on the scale during the annual “weighing ceremony” on January 1

Images from the Lincoln Normal School photograph albums provide an intimate look at theinfluential administrator. Phillips appears as an active, distinguished figure with white upswept hair and wire-frame glasses, easily distinguishable among images of the mostly younger teachers and administrators. Her central presence in the daily life of the school is clear: she appears not only in group portraits with her teachers, but also selling clothes from missionary barrels at the weekly rummage sale, sitting on an improvised sled in a rare snow storm, and swinging gamely from a large scale at the school’s annual “weighing ceremony” on January 1st. Her spotted dog Nick—out to walk in the woods surrounding Lincoln, on the sled, or part of the crowd in group portraits— is a fixture in many of the photos from the earlier album. Clovis Leonder Thompson, whom Phillips married at the age of 70 in 1922, appears in some portraits in the later album. A picture from early in the first album shows Phillips in her own room, reading in front of a fireplace inscribed with the Latin phrase that could have been a personal motto: “Nihil nisi Bonum,” meaning roughly, “nothing but the good.”

Phillips and Clovis Thompson shortly after their wedding

Teachers and Visitors

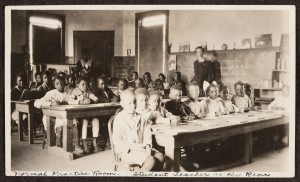

The teachers at Lincoln Normal were, like Phillips, drawn primarily from their association with the New York basedAmerican Missionary Association rather than from the local community; the faculty at Lincoln Normal was until the 1930s primarily white, Northern, and female. (Phillips herself was a child of Scottish immigrants who was raised in Pennsylvania). The images from the Williams Collection reflect this distribution: faculty pictures show no African-American teachers, and never more than one male teacher. One image from the Normal Practice Room captioned “Student Teacher at the Rear” shows an African-American student teacher in the background of a large primary school class. Some of the older Lincoln School students in other photographs may also have been student teachers, as an important function of the LNS long after the move of the teachers’ college to Montgomery remained to train students to teach immediately after their graduation from high school. In the last decades of Lincoln’s operation, as the school began to accept public funding, it fell under segregation laws that shifted instructional demographics dramatically. By 1943 all of the Lincoln Normal School teachers were African American, a state that remained in effect until the desegregation of schools in Alabama prompted Lincoln’s closure in 1970.

Teachers crossing a creek during a picnic outing in the 1920s

A 1919 group portrait of Phillips, the teachers, and Biff the dog

The visitors who are recorded in the Williams Collection photograph albums include AMA administrators from the North and visitors from organizations such as the Ladies’ Aid. Visitors in the school’s later years include Langston Hughes, who read some of his poetry to students and teachers in the early 1930s, and Civil Rights leaders Walter White and Bayard Rustin. Many of the school’s notable alumni were associated with the Civil Rights Movement, including Coretta Scott King, Edythe Scott Bagley, and Jean Childs, the wife of Andrew Young.

Students and Curriculum at Lincoln Normal School

From 1896 to 1922, the student population grew from 150 to nearly 600. At a time when African-American educational institutions were predominantly focused on service-oriented and industrial training, the school in Marion stressed the importance of a more comprehensive education. The spirit at Lincoln Normal was both enterprising and progressive.

Students played a significant role in the upkeep of their own school. From the early days of Phillips’ tenure, when students helped to raise the funds that saved Lincoln, to 1909, when studentshelped the principal to lay bricks for the construction of Van Wagenen Hall, students invested their own time, labor, and money in their institution. Phillips noted that the boys at Lincoln built “a very fine brick building with very little outside help, have built a model cottage, [and] two dormitories.” These last two buildings, finished around 1915, are likely Hope Cottage and Douglas Hall. Once the dormitories were built, students continued to participate in the preparation of what Phillips called “our new self-supporting boarding department”: “Our boys whitened the walls, made washstands and tables out of drygoods boxes, and soon the rooms began, even with this [c]rude home-made furniture, to have a home-like appearance.” A large photograph from the first Williams album captures precisely such a scene: captioned “Boys Kalsomining,” it show two boys of around ten years old on stepladders, whitewashing the walls and ceilings of what could very well be one of the newly-constructed dormitories. As Williams images show, students also participated in other Lincoln community tasks, such as pumping water for their baths and helping to work the school’s farm plot. This spirit of self-sufficiency helps to explain how the Lincoln Normal School was able to grow as quickly as it did in spite of the school’s limited budget.

The curriculum at the Lincoln Normal School was remarkably progressive for the time, and emphasized general self-sufficiency as well as academic literacy. Both sexes learned the practical skills that would be useful to their future lives. As

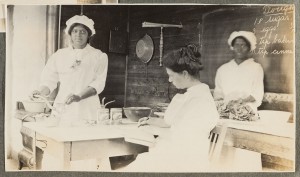

Phillips wrote: “Our cooking and sewing departments are doing a great deal for our pupils. In the advanced classes, we have the boys take lessons in these departments until they can bake biscuit[s], cornbread, cook meat, make a simple cake, darn stockings and sew on buttons. The girls take work in the shop learning how to saw, drive nails, and how to make a knife box of some simple article for the kitchen. Then with great pride the boys exhibit their cake and the girls their knife boxes in chapel some morning.” Photos from the Williams albums show a sewing class of girls hand stitching, and a cooking class in which the lesson, to judge from the blackboard in the background, appears to be cooking a beef loaf and a sweet bread.

A Lincoln Normal School cooking class

Events and Performances

The Williams Collection albums record many special events at the Lincoln Normal School, including Halloween costume displays, Christmas celebrations, picnics, and performances such as plays and musicals. In the case of performances, the albums include particularly detailed documentation of the plays: “The Stolen Flower Queen,” a primary school concert performance, and a “Health Play,” a performance by second graders. The first was a tale of redemption, in which, according to a summary in the second LNS album, the Queen of the Flowers is stolen by the Weeds, who are captured but spared: “After a Council Meeting of the Winds, Flowers, Fairies, etc., it is decided not to kill the Weeds, but to send them to Burbank to be made into useful flowers.” Several images of the performers, some captioned by name, are included. In the images from the “Health Play,” several small performers in costume sing a series of original songs that teach wholesome principles of health and hygiene, set to well-known tunes like this one: “Jack and Jill went up the hill, To fetch a pail of water; A glass before each meal we drink, And never have a doctor.” Several of the performers’ pictures, and their song transcriptions, are recorded in the Williams albums.

Performers from “The Stolen Flower Queen”

Much of the revenue for the school’s maintenance and operations came from a rummage sale that was held every Saturday morning in the school’s store (or storeroom). This sale was a major part of life at the school in the early decades of the twentieth century, and is featured prominently in both of the Williams albums. These Saturday sales resold used clothing that had been collected in Congregational churches in the North and sent down to Lincoln in barrels; they were also known at the school as barrel sales. For the local community, these sales were a source of inexpensive school and work clothing, while they provided income and other useful goods for the school. Customers often bartered farm products in exchange for their clothing, as one image showing two women with produce bags balanced on their heads clearly demonstrates. The weekly sales drew crowds of people, some of whom, like the Lincoln schoolchildren, traveled a significant distance. One portrait that shows a group of 11 triumphantly holding bags and baskets of new possessions is captioned “Went 5 miles for clothes.” Other photos show crowds waiting for the store to open, clothing spread out on long tables, and Phillips participating in the sale.

A Saturday “barrel sale” from 1924