Introduction

The novels of Elise Ayers Sanguinetti were published in the turbulent 1960s. Written against a backdrop of the Civil Rights Movement, they can’t help but grapple with the tension and uncertainty that were hallmarks of those times, especially in places like Mississippi, Georgia, and her home state of Alabama. A journalist by trade and a recent transplant across the Mason-Dixon Line, she saw the integration question — and the national conversation surrounding it — in all its contradiction and complexity.

That conversation about the South was in no small part influenced by the way the region was typically portrayed in 20th century literature. By the 1960s the region was firmly established as the home of gothic fiction, of characters, settings, and stories tending toward the grotesque and the scandalous. It was easy to feel that the reading public knew Southerners and their attitudes only in disturbing caricature.

Enter Elise Sanguinetti. Such a complex literary and cultural background would be enough to make her creative output of interest to scholars. The real value of her work, however, to the general reading public as well as to literary critics and historians, is in the quality of her writing and her particular approach to depicting Southern life.

Take, for example, her first novel, The Last of the Whitfields (1962). In this debut, she bucked expectation by treating the modern South with humor, served up by a charming but predictably flighty thirteen-year-old narrator. Many praised her choice of tone as a refreshing change of pace, but some reviewers didn’t understand how a narrative could be both funny and really meaningful. In an interview in 1962, Sanguinetti lamented, “We don’t take our humorists seriously any more, if we ever did, and we also dismiss the fact that it’s only out of pain that humor grows.”

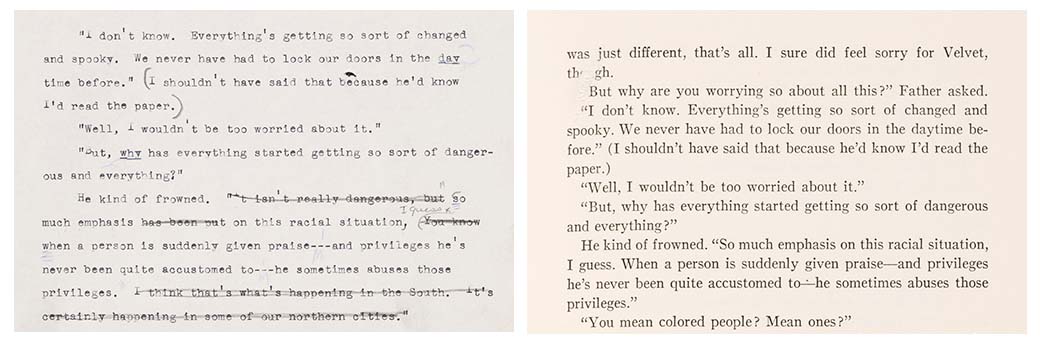

Clearly, Sanguinetti aimed at a delicate balance as a novelist, offering both frankness and compassion, absurdity and pathos. By most accounts, she was successful. Whether focused on a teenage girl’s first taste of the bitter realities of adulthood (The New Girl, 1964) or the frustrations and regrets of a widowed mother (McBee’s Station, 1971), she demonstrated an insightful and sympathetic understanding of her protagonists — at a time when “normal” yet compelling Southern characters were in short supply. As a reviewer at the St. Louis Post Dispatch put it, “She is intent upon creating real people rather than producing gothic gloom or social criticism.”

She was no less skilled at bringing to life a place and time. While most of her work is set in fictional Ashton, Georgia, she also sends her characters to Charleston, South Carolina. That city was made a character in its own right in her third novel, The Dowager (1968).

Biography

Sanguinetti was born Edel Elise Ayers in 1924 in Anniston, Alabama. Daughter of Harry Mell, a newspaperman, and his wife, Edel Ytterboe, she was a decade older than her brother, Harry Brandt. An eclectic education — including high school years spent at a boarding school in South Carolina and semesters of college in far-away Minnesota and even-farther-away Norway — became part of the fabric of her stories as much as her Alabama upbringing. She was especially shaped by her time at the University of Alabama (A.B., 1946), where she was mentored by creative writing professor Hudson Strode.

In 1950, she married Phillip A. Sanguinetti (1920-2020), a chemical engineer from Virginia, and they lived in Pennsylvania and Missouri. Eventually, though, the Sanguinettis returned to Alabama, where after the death of her father she worked at the Anniston Star newspaper, under her mother’s leadership. She died in 2014.

About the Collection

This digital collection, drawn from Sanguinetti’s personal papers, allows general readers as well as scholars to see the development of her style and the evolution of her portrayal of Southern life. It includes personal and professional correspondence, personal photographs, annotated revisions of her published works, and manuscripts of her unpublished works, including the novels Mothers and Daughters, Summer Afternoon, and Call Back Yesterday, and the short story “The Lord Shall Descend from Heaven with a Shout.”