Emancipation

Freedmen faced an uphill battle once they were emancipated. Not only did they deal with the question of how to live independent lives as full citizens, including finding family they’d been separated from, but they also dealt with a wealth of attitudes about their freedom — as well as finding ways to express their own feelings on the matter.

whether free or not

From a brief 1866 piece satirizing the new Freedman’s Bureau Bill. In its display of anger over the rights of ex- slaves, it uses a racial epithet which we have chosen to remove.

1. Every Freedman shall have a bureau for himself with a looking glass on the top, if he wants it.

2. Every Freedman shall have a secretary.

3. Every freedboy or freedgirl shall have a wardrobe.

4. Every freedchild shall have whatever it cries for.

5. White people, whether free or not, much behave themselves.

6. All persons of every color, except red, must vote.

7. Every free white male citizen of the age of 21 years or under, and of sound mind or otherwise, may vote if he will take an oath that he would be a [——] if he could.

“A New Freedman’s Bureau Bill to be Passed Next Session,” Marengo Recorder (Linden), Aug. 29, 1866.

A Paternal Attitude

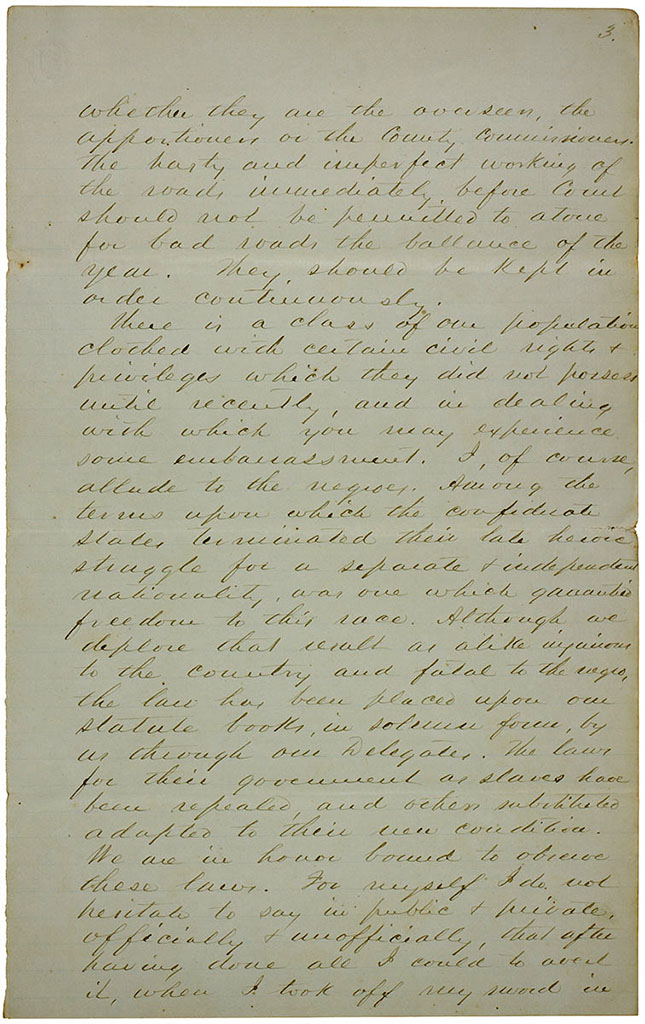

There is a class of our population clothed with certain civil rights & privileges which they did not possess until recently, and in dealing with which you may experience some embarrassment. I, of course, allude to the negroes. Among the terms upon which the confederate states terminated their late heroic struggle for a separate & independent nationality, was one which guarantied freedom to this race.

Besides all this, do we owe the negro any grudge? What has he himself done to provoke our hostility? Shall we be angry with him because freedom has been forced upon him? Shall it excite our animosity that he has been suddenly, and without any effort on his part, torn loose from the protection of his kind master? You may have been that master. He is proud to call you master yet. In the name of humanity let him do so.

From an 1866 charge to a grand jury by Judge H. D. Clayton. He advises kindly behavior toward African Americans, who he sees as inferior and in need of the protection of whites. It also perpetuates the idea that enslaved people did not want freedom.

A partial text of the speech can be found on the Transcripts page.

Henry De Lamar Clayton Sr. papers (Digitized item) (Info about the collection)

the road we have come

It has been said to-day that the great struggle which has just closed with the ratification of the XVth Amendment, commenced nearly one hundred years ago, when this government was formed; but I date it beyond this, to that year when the slaves were landed in Virginia, and the Puritans at Plymouth Rock.

Instead of acknowledging the negro as a man, and making a political friend of him, your course was to alienate him; instead of making him feel himself at home, that he had a country to love — one he was soon to have an interest in — your course was to dissatisfy him, and you told him if he did not like things here, he could go to Africa; they told me that. My reply was, I had no home in Africa; that I was born in Alabama, and did not know any other place; that my mother and father were buried in this State, on the banks of the beautiful Tennessee river, and that I expected to stay here.

From an 1870 speech by James T. Rapier, a future U.S. Representative from Alabama, as transcribed in the newspaper. It reflects on the founding principles of the country, reviews the sacrifices of abolitionists, and discusses the Civil War.

“Speech of Jas. T. Rapier, Esq.; Delivered at the Celebration of the Ratification of the XVth Amendment, Tuesday, April 26th, 1870,” Alabama State Journal (Montgomery), Apr. 29, 1870.

sold by their master

Information Wanted

Of Lina Bell’s Children, sold at different times; Matilda Monday and her Children, owned by Miss Mary E. Bronaugh — Lavinia, Daniel, Ann and Cinda Monday; Andrew Jackson, Solon, Ann and Lucy Bell, sold by their master Wm. B. Stone of Stafford County, Va.

G. V. Lawrence, M. C

An 1868 newspaper notice seeking information on several formerly enslaved people related to Lina Bell. Advertisements like this were common in the years after emancipation, especially in African American newspapers.

When trying to reunite families separated by slavery, it was necessary to include the names of not just family members but also former masters. Locations were also vital, as one’s family might have been taken to another state.

“Information Wanted,” Nationalist (Mobile), Mar. 26, 1868.

Persistent Ties

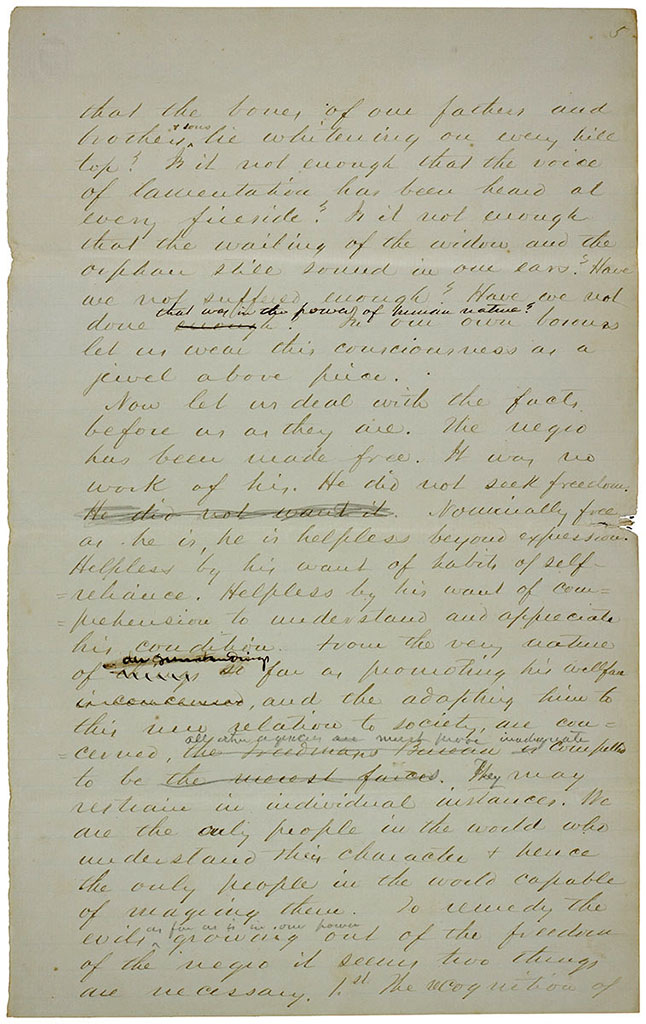

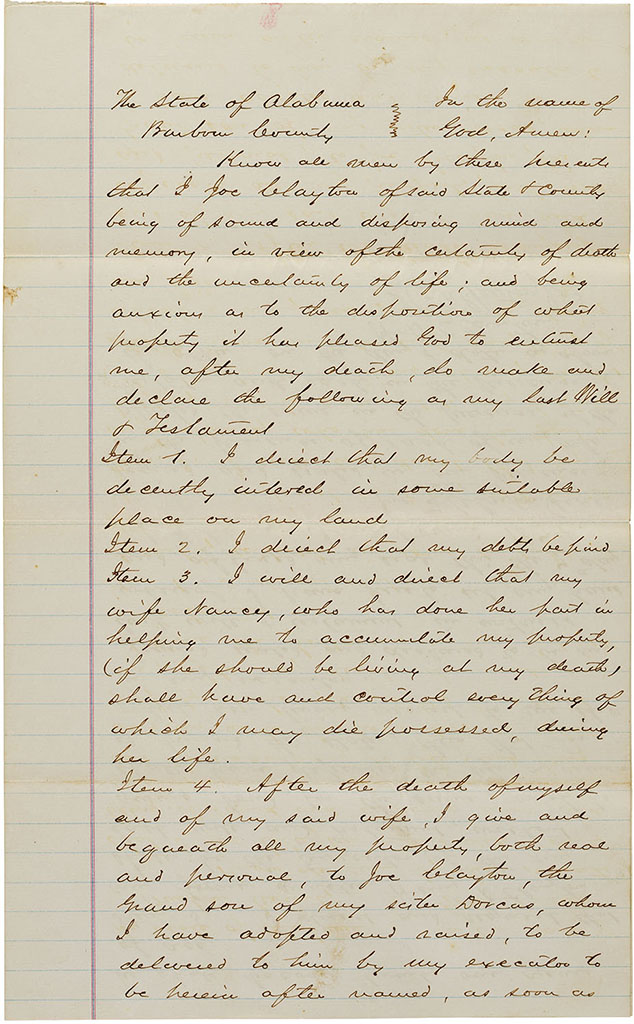

February 1874 will of Joe Clayton, in which he names “my former master Henry D. Clayton” as executor.

Other correspondence and memoir from the Claytons suggests Joe and his wife Nancy had always been close to their master’s family, and that they remained so after they gained their freedom. This document and census records seem to corroborate this.

Henry De Lamar Clayton Sr. papers, MSS.0313. (Digitized item) (Info about the collection)

Freedom

As institutions like the Freedmen’s Bureau helped care for and improve the lives of the formerly enslaved, Black Southerners established their own schools and churches and fought for political positions that would allow them to advocate for the welfare of their communities.

Alabama had three Black U.S. Representatives during Reconstruction:

- Benjamin Sterling Turner (1825-1894) was born into slavery in North Carolina and brought to Alabama at age 5. After emancipation, he was a merchant in Selma and a local politician. He was elected in 1870 to the 42nd U.S. Congress (March 4, 1871 – March 3, 1873). (Read his entry in the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress)

- James Thomas Rapier (1837-1883) was born to free people of color in Florence, and he was educated in Nashville, Tenn., and Ontario, Canada. After the war, he became a cotton planter. He was elected in 1872 to the 43rd U.S. Congress (March 4, 1873 – March 3, 1875). (Read his entry in the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress)

- Jeremiah Haralson (1846-1916) was born into slavery in Georgia and later brought to Alabama. He was a farmer in Selma and a state politician. He was elected to the 44th U.S. Congress (March 4, 1875 – March 3, 1877). (Read his entry in the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress)

Education

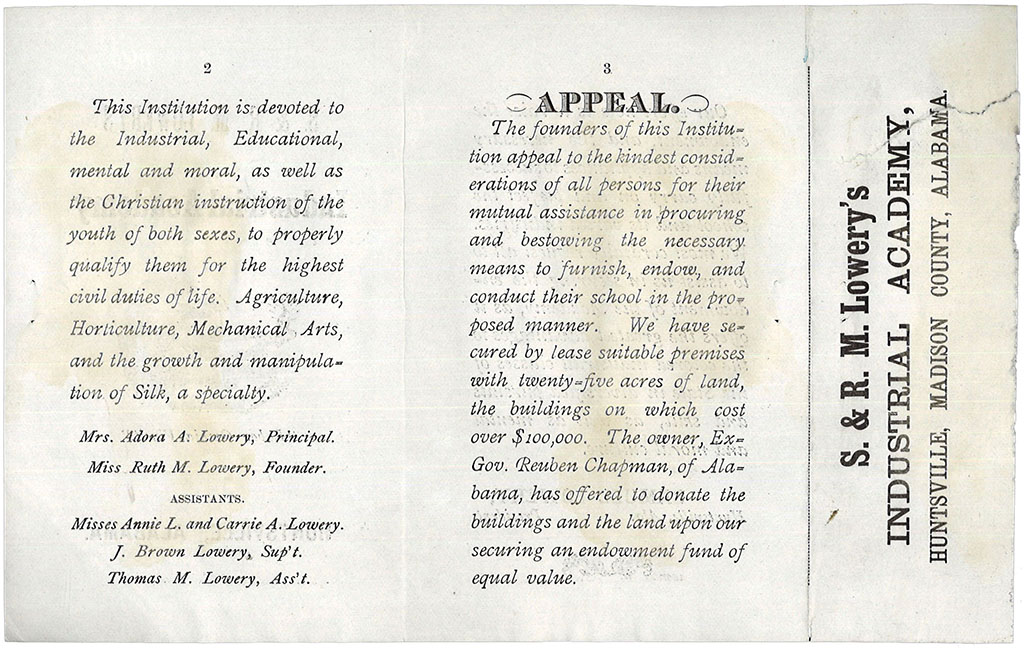

An 1870s fundraising flier for an African American school in Huntsville run by Samuel and Ruth Lowery. A co-ed institution, it focused on industrial and agricultural training.

The flier explains that antebellum governor Reuben Chapman, a former slave owner, has pledged to donate the land and facilities they are leasing — if they can raise a matching sum. Although he may have been acting out of paternal feeling, this was more likely a financial strategy.

Wade Hall Collection of African American Materials, MSS.4274 (Info about the collection)

Religion

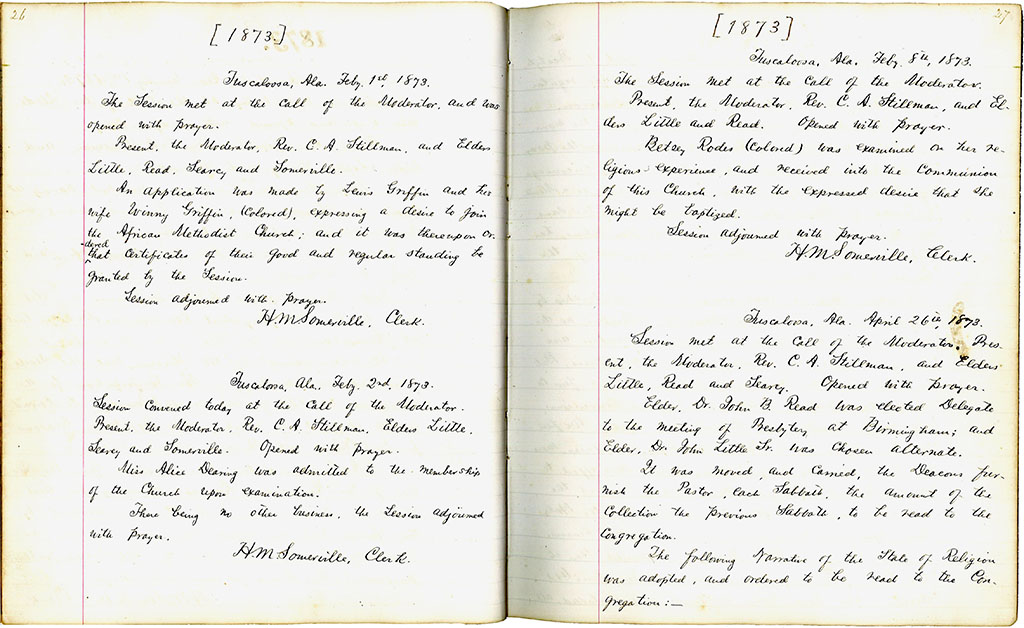

An application was made by Lewis Griffin and his wife Winny Griffin, (Colored), expressing a desire to join the African Methodist Church; and it was thereupon ordered that certificate of their good and regular standing be granted by the session.

Betsey Rhodes (Colored) was examined on her religious experience, and received into the Communion of this Church, with the expressed desire that she might be baptized.

From Feb. 1873 meeting minutes of First Presbyterian Church in Tuscaloosa. It shows the movement of African Americans out of — and, surprisingly, into — this mostly white congregation.

A local Presbyterian church for African Americans was not formed out of this body until 1879.

First Presbyterian Church, Tuscaloosa, Alabama, records, MSS.0518 (Info about the collection)

Health

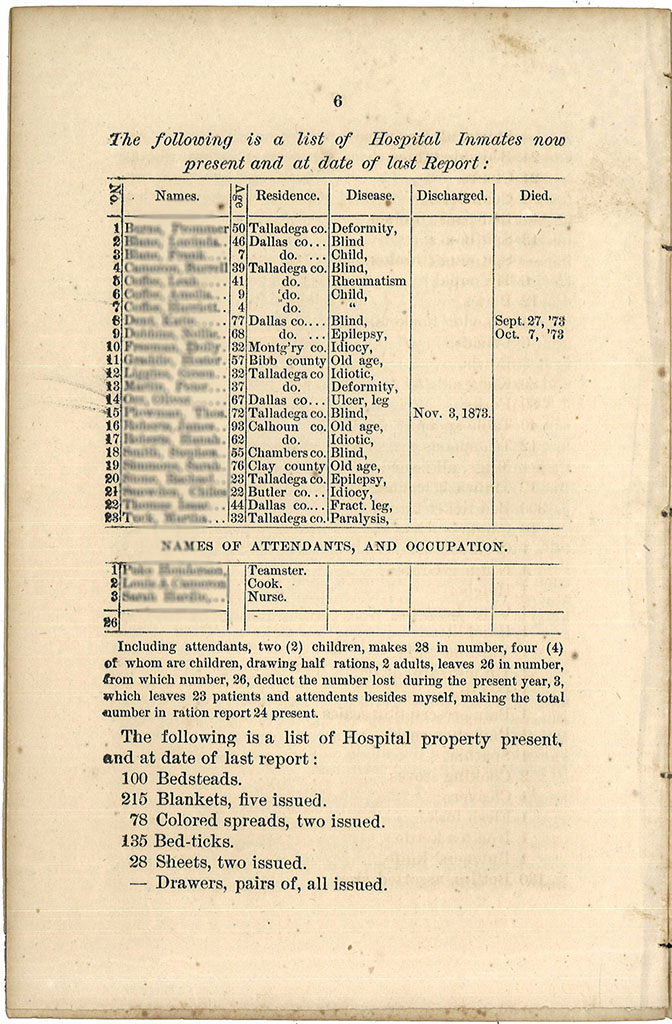

From an 1873 report on the Freedman’s Hospital in Talladega. It details expenses as well as the health of its 23 “inmates,” who came from several central Alabama counties. Their names have been blurred to protect their privacy. Note that the list includes three children of patients that were resident there as well (see people identified as “Child” in the Disease column).

Report of the freedmen’s hospital, for the year ending 1873 [Alabama Collection, RA982.T2 F8 1873]

the greatest of these

The Radicals of this State will be represented in the lower House by three members — one from each of the classes of people comprising their party in the Southern States — Buckley, carpet-bagger; Hays, scalawag; and Turner, negro. Buckley, Hays, Turner — these three — and the greatest of these is Turner.

From an 1871 article backhandedly praising Alabama’s first African American U.S. Representative, Benjamin S. Turner. Here, three Republican politicians are presented in a parody on the familiar Bible passage about faith, hope, and love (1 Cor 13:13). Turner is, like love, proclaimed the “greatest” of the three. However, the article makes sure to remind the reader that, in addition to being Black, Turner is a former slave — albeit one who “conducted himself with propriety and fidelity.”

It describes his intellect as being on par with most other House members, with the implication that none are very smart. But it gives him the edge in morality due to his raising among whites before the war:

The principles he imbibed under such training made him an honest man; and, if he is not one now, it is chargeable to his associations of the last five years.

“Forty-Second Congress,” Selma Dollar Times, Mar. 4, 1871.

Freedmen Politicians

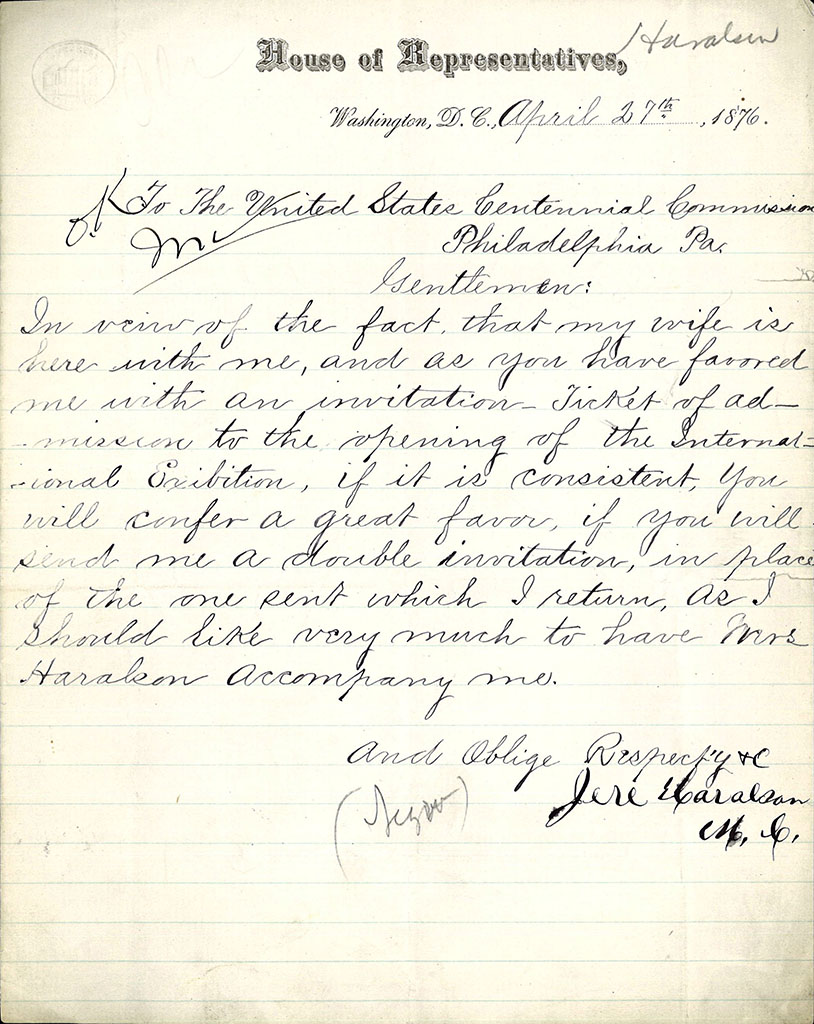

Gentlemen:

In view of the fact that my wife is here with me, and as you have favored me with an invitation Ticket of admission to the opening of the International Exibition, if it is consistent, you will confer a great favor, if you will send me a double invitation, in place of the one sent which I return, as I should like very much to have Mrs Haralson accompany

me.

And Oblige Respecf’y &c

Jere Haralson

M. C.

An Apr. 27, 1876, letter from Jeremiah Haralson, an African American U.S. Rep. from Alabama, to the committee on the Centennial International Exhibition, Philadelphia, the first world’s fair held in the U.S.

Jere Haralson letter, MSS.0625 (Info on the item)