The Labor Question

Many things would have to change about life in the post-war South, but the most pressing problems early on were about the essentials — where and how the newly freed would live and whether they could be persuaded to keep their former masters’ plantations running as employees rather than slaves.

Labor Negotiation, 1865

Hand transcription of a June 1865 labor contract between planter and Baptist minister Basil Manly and 28 people formerly enslaved in his fields and house — now declared “freedmen & freedwomen, by the yankees.”

He records their names, listed below, along with the symbols they used in place of signatures.

Winter, Wood, Peter, William, Archy, Andrew, George, Robert, Alick, John, Henderson, Edmond, Oliver, Levi, Judy, Ron, Patsy, Martha, Sabra, Rebecca, Priscilla, Lydia, Binky, Ann, Old Sabra, Julia, Morris, Arthur

In ten weeks’ time, all but four of them would abandon the agreement and the plantation.

Text of the whole diary entry with contract can be found on the Transcripts page.

Manly Family papers, MSS.0900 (Digitized item) (Info about the collection)

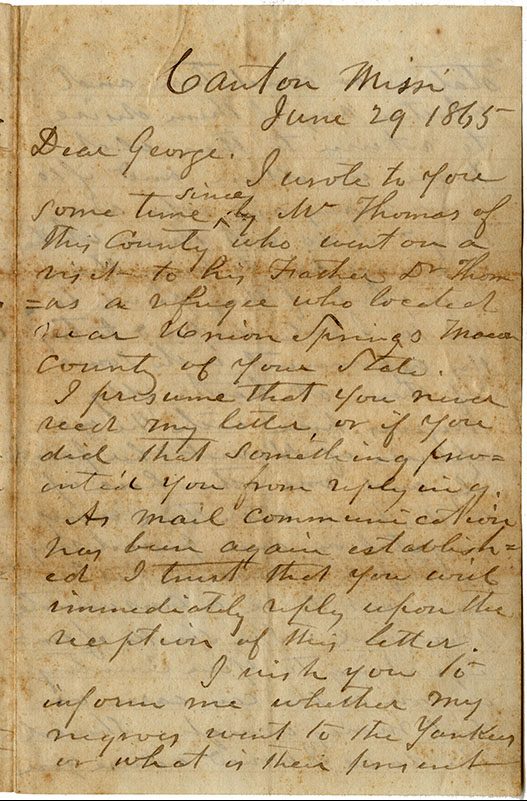

White Fears

I wish you to inform me whether my Negroes went to the Yankees or what is their present status or condition and whether any of them desire to return to their old home in Miss and if so how many and who are they.

A June 1865 letter from Mississippi planter O. A. Luckett to George, presumably a friend or trusted employee, in Alabama. He inquires about the status of his former slaves, apparently wishing them to return to his plantation. He later asks about his mules and carriages, saying they were now worth more to him than the people he lost to freedom.

Later he expresses his hopelessness about the future (“we are all ruined, and no mistake”) and says he plans to leave the country as soon as possible: “I feel inclined as soon as I can make the means to emigrate to some other part of the world.”

Wade Hall collection of Civil War materials, MSS.4273 (Digitized item) (Info about the collection)

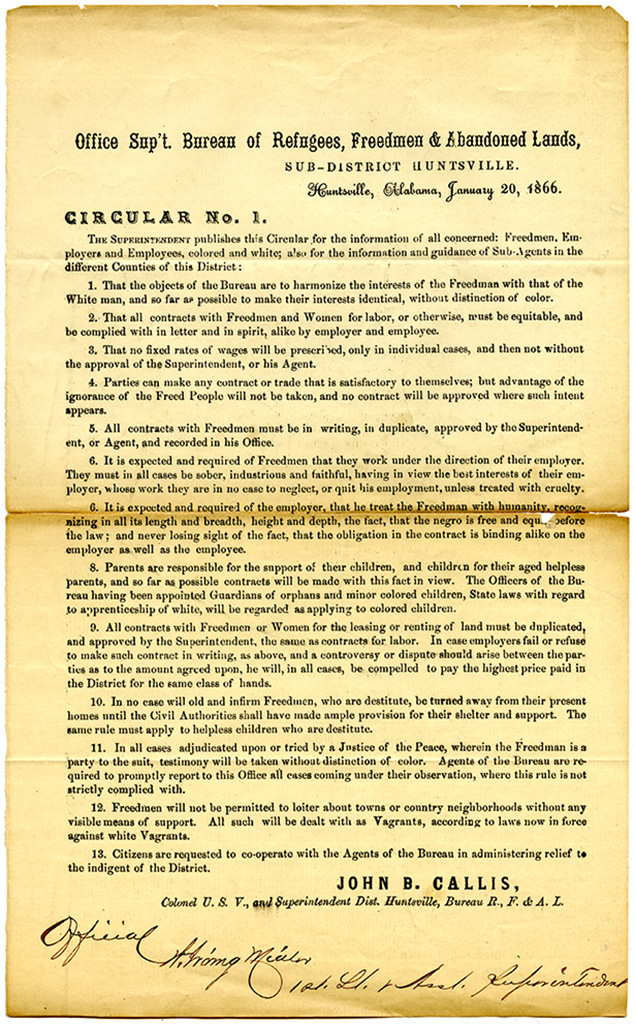

Freedmen and Labor

A Jan. 1866 Freedmen’s Bureau circular, explaining its role in brokering labor contracts between freedmen and plantation owners.

No. 6 explains that contracts are binding on both parties: Workers are expected to work hard, obey their employer, and stick with the contract — “unless treated with cruelty.” Employers are required to treat workers humanely, recognizing that “the negro is free and equal before the law.”

No. 12 specifically warns freedmen against loitering. This could make them subject to anti-vagrancy laws, enacted after the war to make it easier to arrest people of color and force them into involuntary labor. Such discriminatory laws, referred to as Black Codes, were quickly invalidated by several pieces of Reconstruction legislation.

Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands broadside, MSS.4052 (Info about the item)

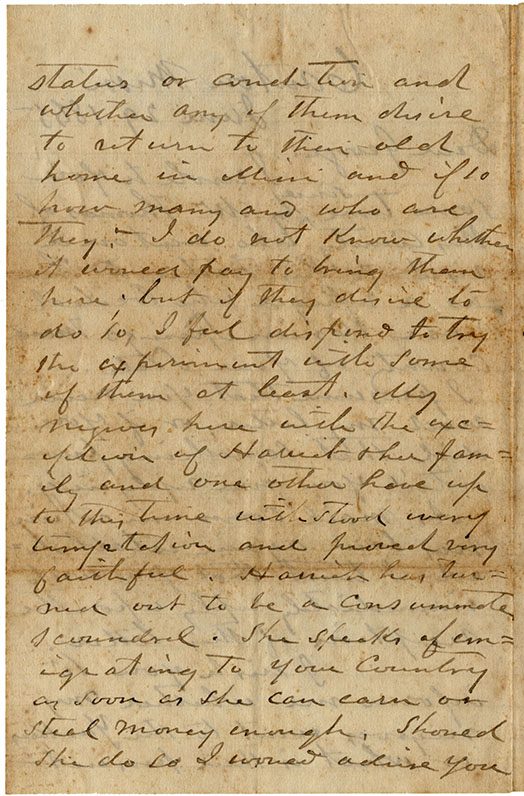

Labor Negotiation, 1867

A January 1867 contract between John Cocke and a group of more than 50 laborers, “freedmen of color.” It is a detailed agreement reflecting new norms of labor and prefiguring greater responsibilities toward freedmen under Reconstruction.

The brackets in the document seem to indicate families, many of which contain children, based on comparing the names enumerated and the number of signers on the document. Signers are indicated with asterisks in the list below:

[Henry] Rea, Catherine, *William, Jarrat, Pat, *Ed, *Itt, *Charlotte, *Alen, Ras, Jim Nick, Nan, Joe, Sally, *Charity, *Maria, *Sophia, *Sini, *Georgia, Charles, Philis, *Delia, Peter Jones, Tamar, Stephen, Julia, *Stephen Jr., [?], Mary, *Jerry, *Martha, Spencer, Sara, *Alace, *Emily, *Susan, *[?], Harry, Shack, Antony, Harriet, *[?], *Maria, Theophulus, Sol, Katy, *Mary, *Sally, *Margaret, *Ely, Manerva, *Harriet, *Oscar, Roger, Nancy

Text of the document can be found on the Transcripts page.

John Cocke papers, MSS.0328 (Digitized item) (Info about the collection)

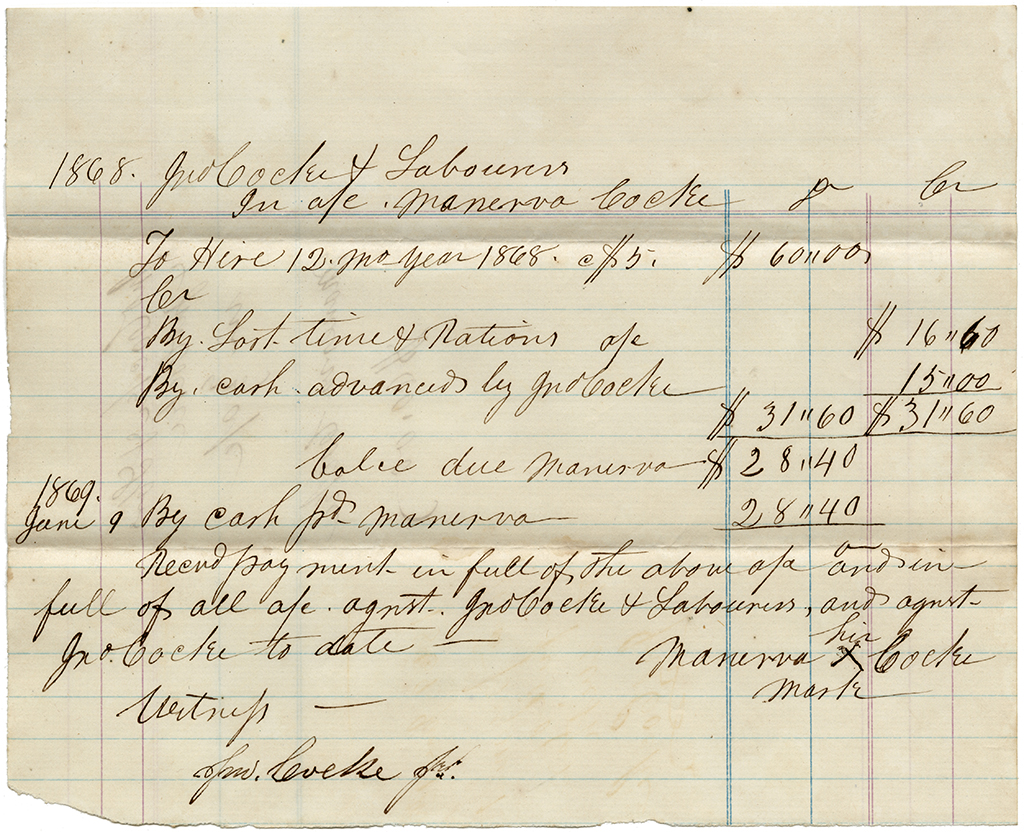

Freed(wo)men and Labor

A June 1869 receipt settling the account of Manerva Cocke, formerly enslaved to Greene County planter John Cocke but now a paid laborer. It details her earnings for 1868, minus lost work time, rations, and cash advances — which in effect reduced her pay by half.

Like most former slaves, Manerva signs with a mark, indicating she is illiterate. She has been given the last name of her former master, a common practice, although it’s unclear whether this was her choice.

Evidence in other receipts suggest that this payout was for the labor of both Manerva and her daughter Harriett.

John Cocke papers, MSS.0328 (Digitized item) (Info about the collection)

Flight

While some Alabamians tried to adapt to a new way of life, many, Black and white, instead fled the region. Whites were more likely to travel south to parts of Latin America, where they were known as confederados. Freedmen and women often moved west to the American frontier or over the ocean to the African country Liberia, settled by free and freed Black Americans in 1822.

superior advantages

Shortly before 1835, the slaves were set free, and ever since the negroes have sustained the most kindly and subordinate relations toward their old masters, to whom they are grateful for their voluntary emancipation.

From an 1867 letter from a white emigrant to modern Belize, then a British colony, printed in the newspaper. Perhaps to entice Southerners, it paints a picture of emancipated slaves as highly dependent on their former masters.

“British Honduras,” Elmore Standard (Wetumpka), May 22, 1867.

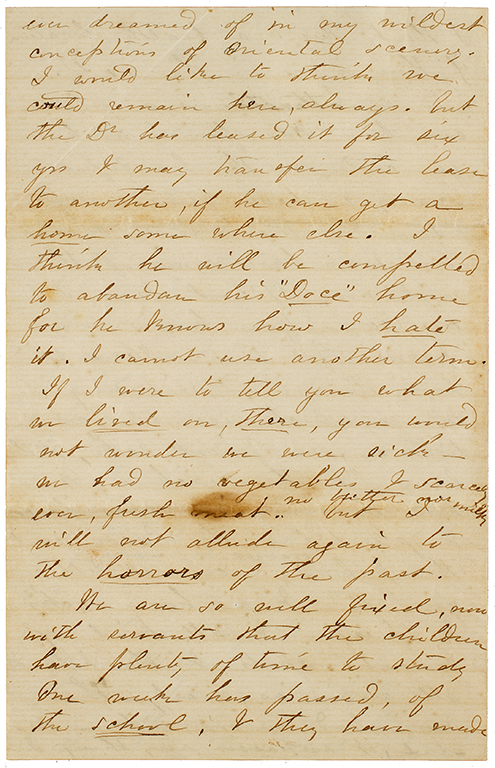

Leaving the South

I think he will be compelled to abandon his “Doce” [sweet] home for he knows how I hate it. I cannot use another term. If I were to tell you what we lived on, there, you would not wonder we were sick — we had no vegetables & scarcely ever, fresh meat. no butter nor milk. but I will not allude again to the horrors of the past.

From an Aug. 14, 1868, letter from Montgomery native Julia Hentz Keyes on “Dixie Island” near Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, to cousin Mary in Montevallo. Julia and her husband and six children left the United States after the war to settle in a country where slavery was still legal. The family returned to the U.S. in 1872, but three of the children later moved back to Brazil to raise their own families there.

Compare to a letter written to Mary on the same day by Julia’s daughters Jennie and Julia. It discusses some of the same recent history, regarding their standard of living and bouts of illness, but in less detail, and the present is framed more positively.

Keyes Family papers, MSS.0813 (Digitized item) (Info about the collection)

here we are masters

Brethren, I beg you, as one who wishes you well, to come over and help cultivate this rich soil, and by doing so we shall gain favor with all the leading powers of the earth, and particularly with the people of the United States, who are our friends when we get here.

But if you stay where you are, I know too well what is going to become of you.

From an 1868 letter printed in the newspaper, written by an Black American who had recently moved to Liberia. He advocates that Blacks move out of the U.S., as whites will constantly fight them if they remain, an attitude he claims to understand. This separatist approach to race conflict is not surprising — it was the reason Liberia was founded.

Text of the whole letter and the editorial comments that introduce it can be found on the Transcripts page.

Larkin Y. Creagher, letter to the editor, printed as “Letter from Liberia [reprinted from Mobile Tribune],” Livingston Journal, Oct. 2, 1868. [via Newspapers.com]

open to all

Politically, she is one of the most radical States in the Union. Her schools are open to all, and as soon as the amendment of her Constitution, already determined on, can be legally effected, the last barrier will be broken down, and the admission of colored men to the polls will put her by the side of Wisconsin and the New England States.

From an 1866 article touting Kansas as a good alternative to moving north for freedmen. In addition to describing the good quality of the land, it notes that the state is welcoming to people of color.

“Kansas,” Nationalist (Mobile), May 17, 1866. [via Newspapers.com]

untold wealth

The term “wilderness” is applied to the South, because it is only at this time in an embryo state of development. Those of us who were born and raised on its generous soil, are accustomed to think that all that is necessary to develop her untold wealth is industry on our part in utilizing the resources at command; but while this is true in part, yet the inadequate supply of labor to the great and increasing demand must be patent to all the outside world.

From an 1872 article on labor shortages in the post-slavery South. Instead of probing into the cause and effect that led to this problem, it focuses on the romantic: it explains that while Alabama, a relatively young state, has much potential, it can only realize it with workers to tame the “wilderness.”

Text of the whole article can be found on the Transcripts page.

“Immigration,” Gadsden Times-News, July 11, 1872. [via Newspapers.com]

![Handwritten document, text as follows: June 20 tuesday – This day, at the plantation made an arrangement with my negroes to work on my place, being declared freedmen & freedwomen, by the yankees. The arrangement includes my home-servants at home. They are to have the productivity of ten average acres of corn. The following is a copy of the contract, & the names of the signers.

“We, the undersigned, declared ‘freedmen & freedwomen’ by the U.S. military authorities, and residing on the plantation of B. Manly, near Foster’s ferry, Tusk., W. Ala., do hereby agree to continue to work on the said plantation, under the direction of said Manly or his agent; to use due diligence during the customary number of hours, daily, to take care of all the stock, implements, or other property on the place or committed to us severally; and to act faithfully as laborers and employees on said plantation in all respects, until the close of the present year, on pain of being dismissed therefrom by said Manly of his legal representative by his desire. And we do also hereby agree to receive as full compensation for said services, the food, clothing, house-room, fuel and medial attendance in actual sickness, of ourselves and families; and further, that we receive to productions of a lot of ten (10) acres of land, to be selected as an average of the crop of corn; to be divided [?] among us at the close of the year.

As witness of our freely & voluntarily agreeing hereunto we have affixed our marks opposite our names, to this paper, before witnesses, at the said plantation, this 20th day of June, A.D. 1865.

Winter, Wood, Peter, William, Archy, Andrew, George, Robert, Alick, John, Henderson, Edmond, Oliver, Levi, Judy, Ron, Patsy, Martha, Sabra, Rebecca, Priscilla, Lydia, Binky, Ann, Old Sabra, Julia, Morris, Arthur

I, B. Manly, as named in the preceding instrument, do hereby [express?] my agreement to employ the persons whose names are thereunto attached, according to the terms thereof.

Given, under my hand, the day & date before written.

B. Manly

Signed in presence of

John C. Foster

Joshua H. Foster

This was presented to the U.S. military authorities in Tusk. on Thursday July 6th and approved.](https://apps.lib.ua.edu/blogs/digitalexhibits/files/2020/05/Recon_Sec1_Manly.jpg)

![Handwritten document, text as follows: Green County State of Alabama Jan 14th 1867

Memorandum of and an agreement made and entered into between John Cocke party of the first part and the following named persons freedmen of color vis. (Rea Catherine William) Jarrat Pat Ed Itt Charlotte Alen) Ras) Jim Nick Nan) Joe Sally Charity Maria Sophia Sini Georgia) Charles Philis Delia) Peter Jones Tamar) Stephen Julia Stephen Jr. [?]) Mary Jerry Martha) Spencer Sara Alace Emily Susan [?] Harry) Shack) Antony) Harriet [?] Maria) Theophulus) Sol Katy Mary Sally Margaret Ely) Manerva Harriet Oscar) Roger) Nancy) Witnesses, they have agreed, and do now agree, and bind themselves, jointly, collectively, individually, and severally, as families, for themselves, and those for whom they have a right to contract — to stay with the party of the first part, untill, the first day of January next, (1868,) work and be under his and the same rules, and regulations, directions, and management &c as heretofore required by him. And, in consideration for their doing and performing the same, the party of the first part, agrees to give them, one half of the nett proceeds, made or raised, on his plantation from said labor, the party of the first part, to furnish provisions, stock, and other things that he may think necessary, and also stock for raising, the same to be returned to him, if on the plantation the first day of January next, if not, in kind if made, or raised, on plantation, if not made, or raised, its value, to be retained, by him out of proceeds. The party of the first part, to hire and overseer, or Agent, at a reasonable compensation, or what is customary in the neighborhood, the party of the first part, to receive for his service such commissions, and compensation, as is allowed by the judge, of the probate court, of Green County](https://apps.lib.ua.edu/blogs/digitalexhibits/files/2020/05/Recon_Sec1_Cocke_contract.jpg)