Occupation & Readmission

Though Alabama, like the rest of the South, was allowed to slide backwards toward the old status quo during months immediately following the war, Radical Reconstruction, beginning in 1867, put a stop to that. It provided for the protection of freed people and made mandatory the kind of sweeping social justice measures that the state would otherwise not have enacted — without a new constitution and ratification of the 14th Amendment, states could not re-join the Union.

where unrestrained

In almost every portion of the South there is a disposition among this class to punish the negro for the crime of having become free, and they persecute him in a most merciless manner where unrestrained.

From an 1866 article on the lingering presence of federal troops in the South. It argues this is necessary to prevent the persecution of freedmen, who are a constant reminder of the region’s defeat. In 1867, this post-war occupation would become wholesale military rule.

“Reason for Retaining Troops in the South,” Nationalist (Mobile), Mar. 29, 1866.

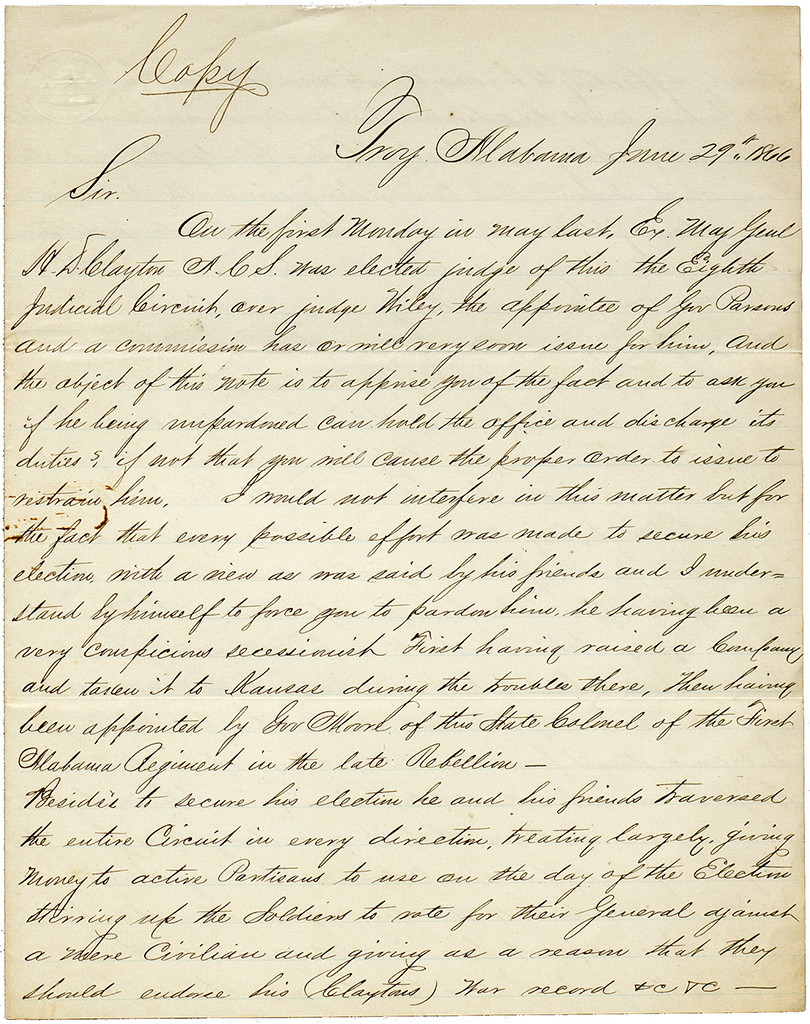

Unpardoned

I would not interfere in the matter but for the fact that every possible effort was made to secure his election with a view as was said by his friends and I understand by himself to force you to pardon him, he being a very conspicuous secessionist First having raised a company and taken it to Kansas during the troubles there, then having been appointed by Gov. Moore of this State Colonel of the First Alabama Regiment in the late Rebellion.

From a June 29, 1866, letter to Pres. Johnson from Troy resident Hugh Giles, questioning whether Henry D. Clayton, once a Confederate general, can legally serve on the state judicial circuit. After the war, former Confederate officers were barred from voting or running for office until they received a federal pardon.

Henry De Lamar Clayton Sr. papers, MSS.0313 (Digitized item) (Info about the collection)

White Frustrations

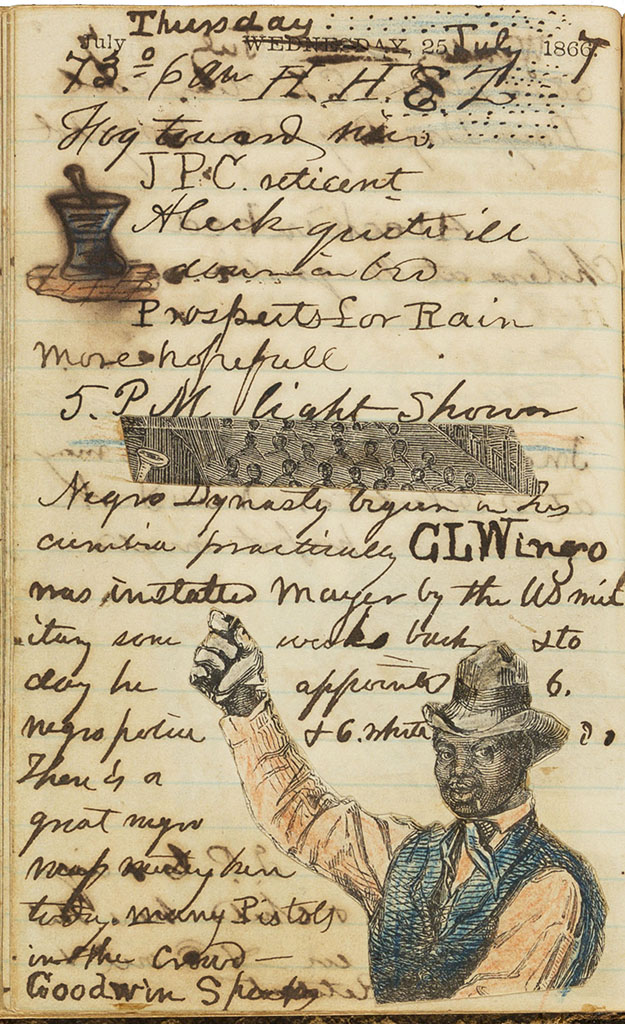

Two 1867 diary entries by William Cooper of Tuscumbia, recording — and illustrating — his experience of life during Reconstruction.

William Cooper diaries and photograph, MSS.0357 (Digitized item) (Info about the collection)

we are suffering

Some of our people were in a great hurry to get out of the Union. Seeing then that we have all felt the disastrous consequences of that move, and that we are suffering, and still must suffer for the want of the protecting care of the government, we see no reason we should not be in equally as great a hurry to get back in the Union. When men are in a hurry to do wrong, they should be in a hurry to repair that wrong when they discover it.

From an 1867 editorial arguing that Alabamians should desire a quick return to the Union. As a “storm rages without,” delaying is “dangerous”.

Partial text of the article can be found on the Transcripts page.

“Restoration of the Union,” Elmore Standard (Wetumpka), May 22, 1867

A New Constitution

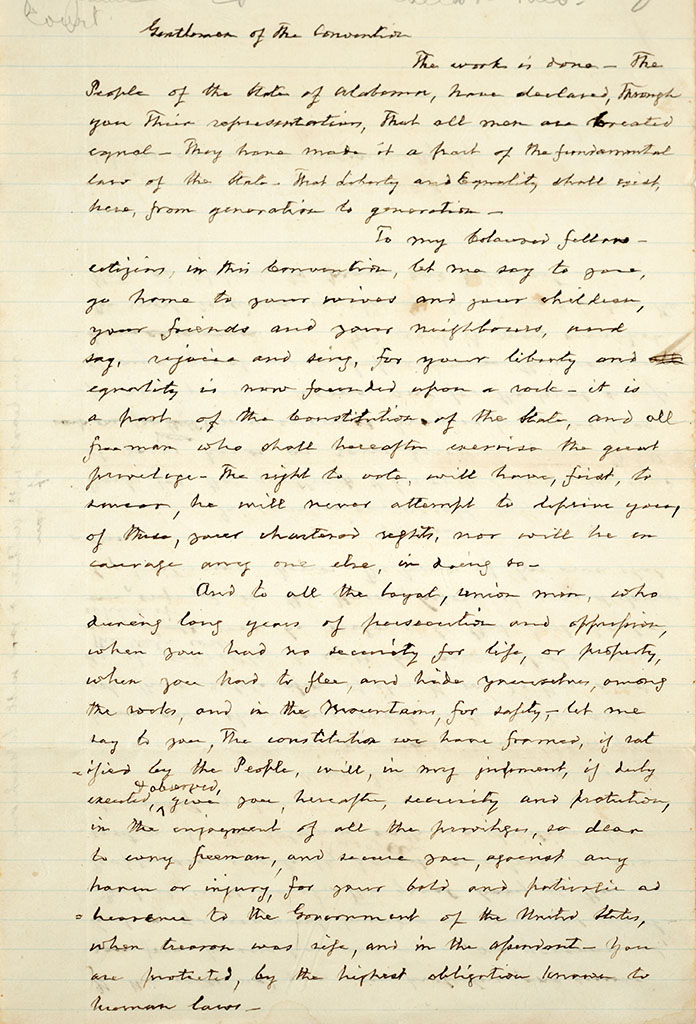

Gentlemen of the Convention,

The work is done. The People of the state of Alabama, have declared, through you their representatives, that all men are created equal. They have made it a part of the fundamental law of the state, that Liberty and Equality shall exist here, from generation to generation.

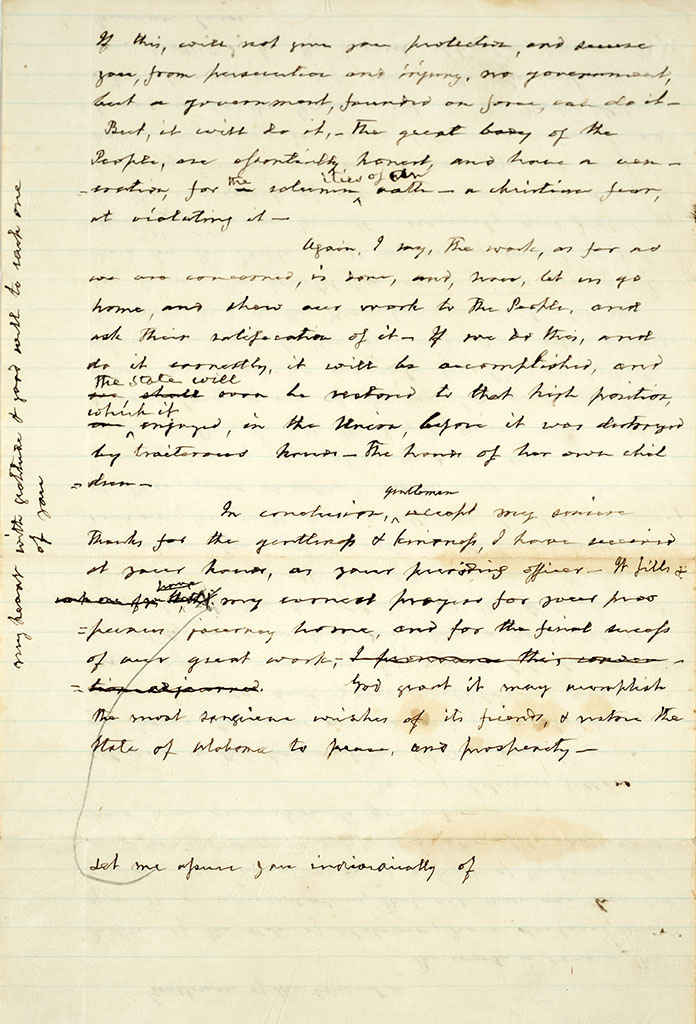

An 1867 draft of a speech before the state Constitutional Convention by its president, Elisha W. Peck of Tuscaloosa. It frames racial equality as the paramount concern of the new document.

Text of the whole speech can be found on the Transcripts page.

Elisha Woolsey Peck papers, MSS.1120 (Digitized item) (Info about the collection)

Pardon & Amnesty

The process of returning ex-Confederates to civic life was long and complicated.

Initially, under President Johnson, it wasn’t too hard to apply for a pardon.

However, the passing of the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution in 1867 once again disqualified these men, and it was much harder to gain a federal exemption:

No person shall … hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may, by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

Article XIV, Section 3

The 1868 Constitution of Alabama upheld this standard:

It shall be the duty of the General Assembly to provide, from time to time, for the registration of all electors; but the following classes of persons shall not be permitted to register, vote or hold office: … 2nd Those who may be disqualified from holding office by the proposed amendment to the Constitution of the United States, known as “Article XIV,” and those who have been disqualified from registering to vote for delegates to the Convention to frame a Constitution for the State of Alabama, under the act of Congress, “to provide for the more efficient government of the rebel States,” passed by Congress March 2, 1867, and the acts supplementary thereto, except such persons as aided in the reconstruction proposed by Congress, and accept the political equality of all men before the law: Provided, That the General Assembly shall have power to remove the disabilities incurred under this clause.

Article VII, Section 3

Finally, the 1872 Amnesty Act was a blanket pardon for most ex-Confederates, paving the way for Democrats, the majority in the region, to retake local and state governments.

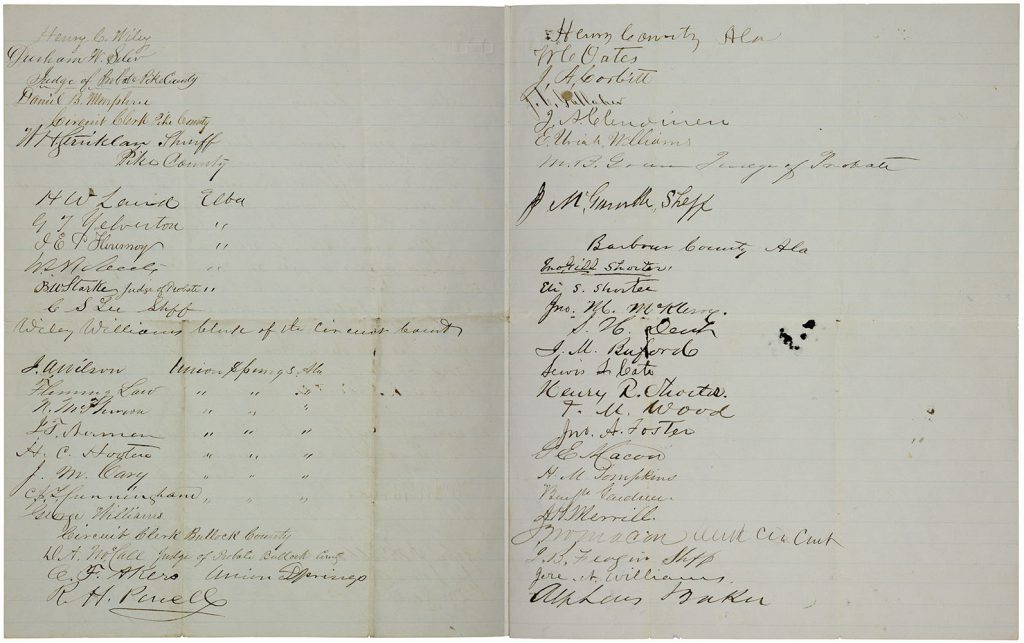

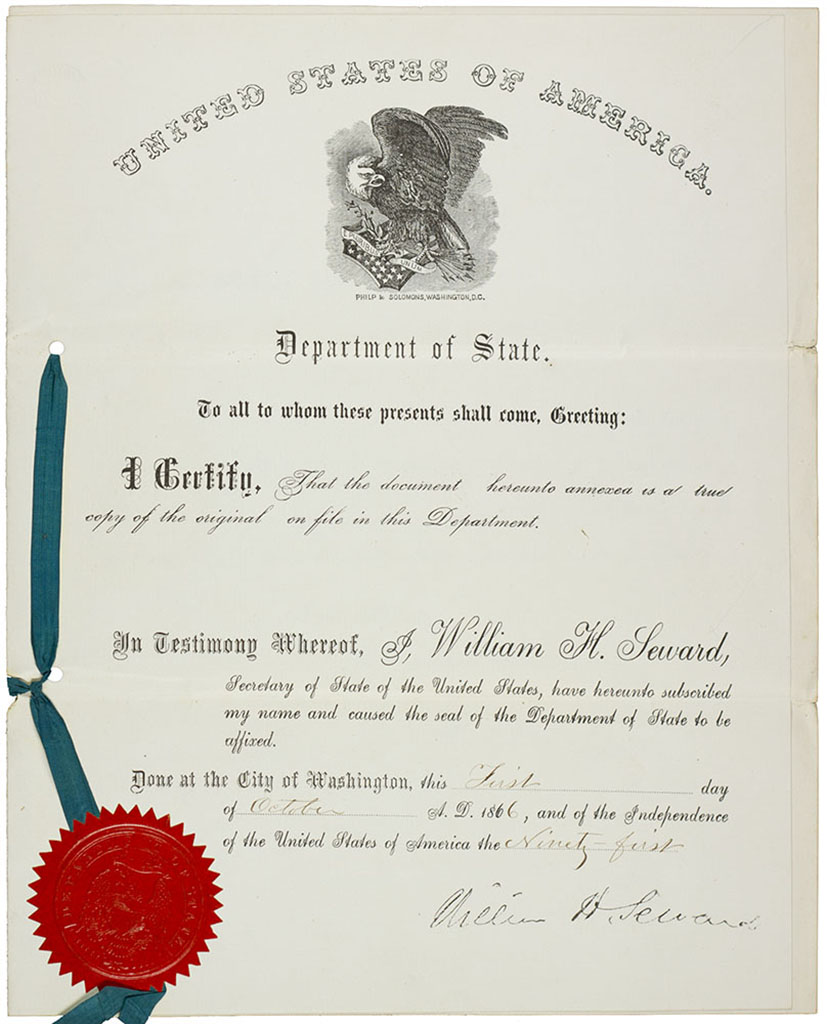

Pardon

The October 1866 military pardon for Henry D. Clayton, signed by William H. Seward, the Secretary of State, on October 1. It allowed the former Confederate General to be elected Circuit Court Judge.

Henry De Lamar Clayton Sr. papers, MSS.0313 (Digitized item) (Info about the collection)

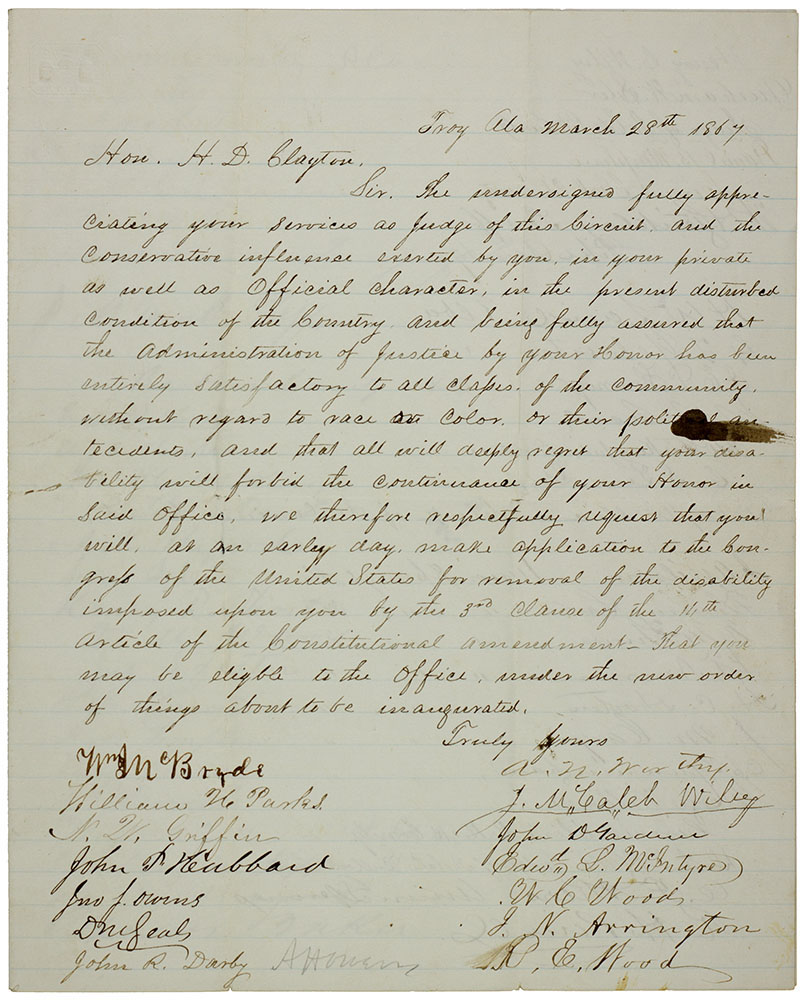

Appeal

Sir. The undersigned fully appreciating your services as Judge of this Circuit and the conservative influence exerted by you, in your private as well as official character, in the present disturbed condition of the County and being fully assured that the administration of justice by your Honor has been entirely satisfactory to all claſses of the community without regard to race or color or their political antecedents, and that all will deeply regret that your disability will forbid the continuance of your Honor in said office, we therefore respectfully request that you will, at an early day, make application to the Congreſs of the United States for removal of the disability imposed upon you by the 3rd Clause of the 14th Article of the Constitutional Amendment. That you may be eligible to the office, under the new order of things about to be inaugurated.

A March 28, 1867, letter to Judge H. D. Clayton signed by 61 of his constituents, asking him to apply for removal of his “disability” under the 14th Amendment, which was passed by Congress and would be ratified the next year.

Evidently, Clayton was not interested in fighting the new federal mandate. He did not return to judgeship until after Reconstruction ended.

Henry De Lamar Clayton Sr. papers, MSS.0313 (Digitized item) (Info about the collection)

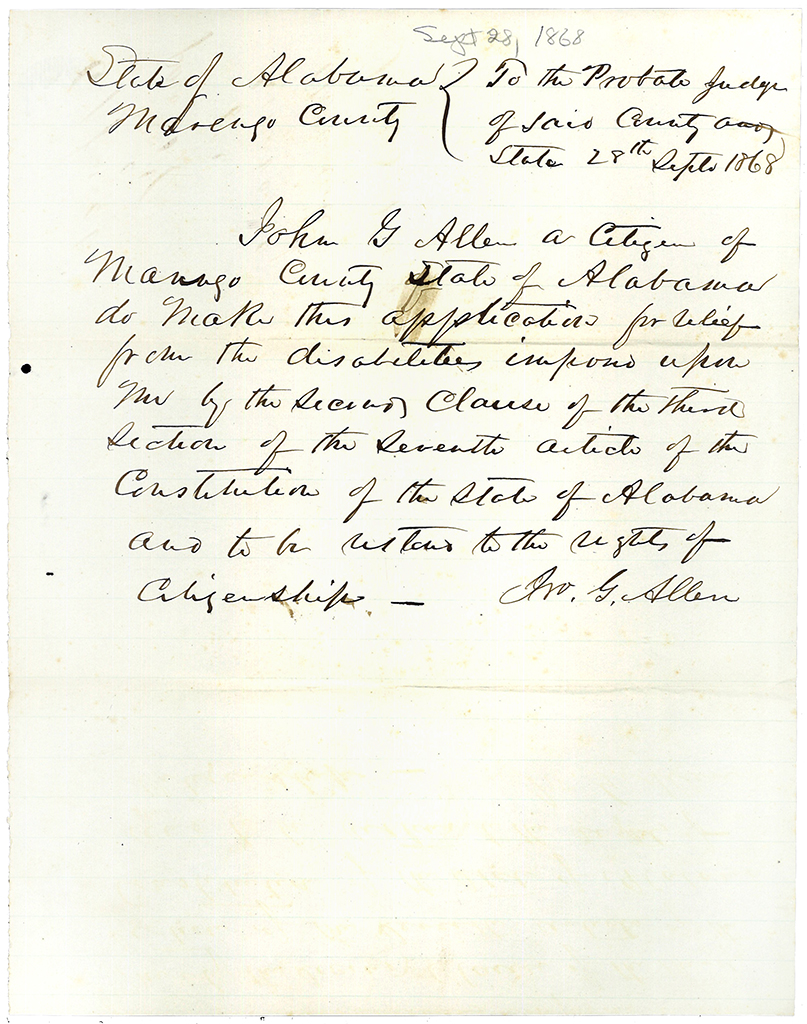

Application for Relief

John G. Allen a citizen of Marengo County state of Alabama do make this application for relief from the disabilities imposed upon me by the second clause of the third section of the seventh article of the Constitution of the state of Alabama and to be restored to the rights of citizenship.

A Sept. 28, 1868, letter from planter John Gray Allen asking a local judge to remove the restrictions preventing him from voting or holding office. The Alabama Constitution clause he mentions both declared the restrictions and provided for their removal.

A note on Allen: Though he had been too old to serve in the Confederate military, the aid he provided to troops was apparently substantial enough to warrant stripping his citizenship after the war.

Allen Family papers, MSS.0064 (Info about the collection)

a sort of amnesty

At last a Radical Congress has been sufficiently magnanimous to pass a kind of amnesty bill that nobody thanks them for. Even this so-called amnesty bill would not have passed had it not been for the amnesty resolution in the Cincinnati platform. This plan in the Greeley platform was known to be strong with the Southern people, and in order to weaken Greeley at the South and to strengthen Grant, the Radicals in Congress have condescended to grant us a sort of amnesty which we certainly are in no humor to exult over. As small a favor as this is the Radical Congress never would have granted if they had not been kicked into it by the action of the Cincinnati Convention. True, this amnesty bill relieves nearly all of our people of political disabilities, but as the time Congress passed the bill, they also adopted portions of Sumner’s civil rights bill which were intended to insult and humiliate the South. We have no thanks to offer for any of these miserable, insulting, grudgingly-given favors.

An 1872 article reacting to the passing of the Amnesty Act. It argues this step was taken simply to weaken Democratic presidential candidate Horace Greeley, who had made it a campaign promise.

“Amnesty,” West Alabamian (Carrollton), May 29, 1872.

now in congress

A newspaper article from 1874 identifies dozens of former Confederate officers who, as of the previous election, would have a seat in the United States Congress. This was possible only because of the Amnesty Act.

The four Alabamians listed there are described below — notably, two of them Republicans and two Democrats.

- Lt. Col. J. H. Caldwell — John Henry Caldwell was a northern Alabama Democrat (first elected on a fusion ticket with the Liberal Republicans). He served in the U.S. House during the 43rd and 44th Congresses (1873-1877). He had been an officer in the 10th Alabama Infantry. See Caldwell’s congress.gov bio

- Maj. Joseph H. Sloss — Joseph Humphrey Sloss was a northern Alabama Democrat. He served in the U.S. House during the 42nd and 43rd Congresses (1871-1875). He had been an officer in the 4th Alabama Cavalry. See Sloss’s congress.gov bio.

- Maj. Charles Hays — Charles Hays was a Republican from the Black Belt region. He served in the U.S. House during the 41st through and 44th Congresses (1869-1877). He had been an officer in the Confederate Army, although it’s not clear with what unit. See Hays’s congress.gov bio.

- Capt. Charles Pelham — Charles Pelham was a northern Alabama Republican. He served in the U.S. House during the 43rd Congress (1873-1875). He had been an officer in the 51st Alabama Partisan Rangers (an irregular volunteer guerilla unit). See Pelham’s congress.gov bio.

“Reconstructed,” Montgomery Daily Advertiser, Jan. 31, 1874.