Mama, put my guns in the ground

“Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door,” Bob Dylan

I can’t shoot them anymore

That long black cloud is comin’ down

Feel like I’m knockin’ on heaven’s door

Aftermath

In June, a committee to investigate the two weeks of unrest was formed, comprising students, faculty, and administrators. It found that elements from all three of these groups were at fault for the way they communicated.

One interesting result of this period of reflection was the assignment of student and faculty “marshalls” to work as liaisons with the University police during future incidents of unrest. The 22-person University police was also required to undergo training, so as to become more “service-oriented.”

Legacy of protest

These days in May 1970 were not the beginning of protest activity at the University, and they were not the end, either. In the months to come, marches and sit-ins would become familiar sights on campus. Two causes spawned lengthy protest actions over the next couple of years:

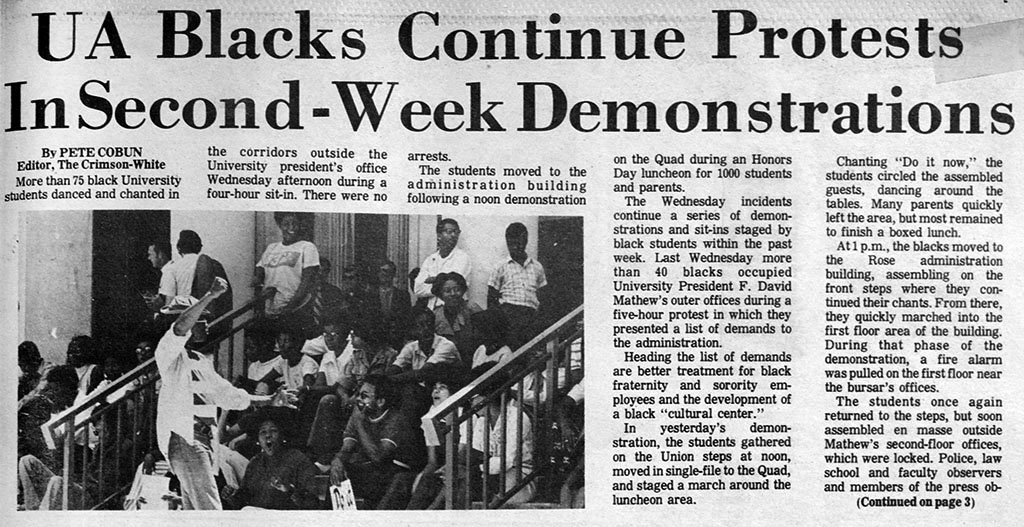

Segregation academy protests (Apr.-May 1971)

Black students protested the leasing of University property to Tuscaloosa Academy, a private school established to allow white students to avoid attending integrated schools (also known as a segregation academy), which led to more general protest for civil rights.

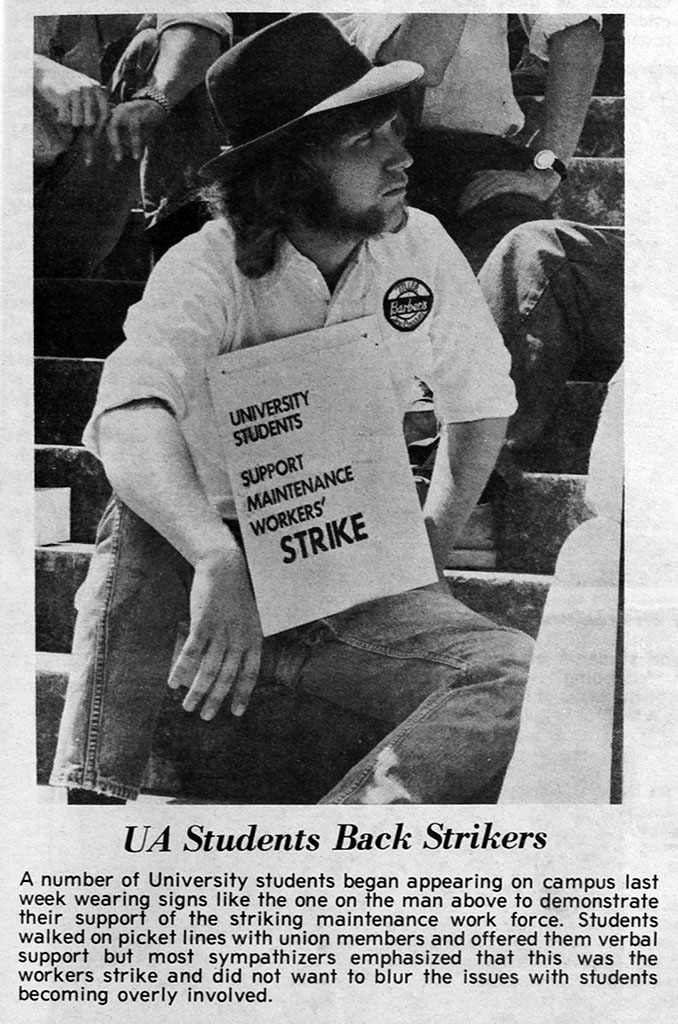

Maintenance workers strike (Sept.-Oct. 1972)

Students supported striking Maintenance Workers Union members, many of whom were Black. As the strike wore on, Afro-American Association members and their allies protested the use of non-union labor by dumping garbage outside Pres. Mathews’s office.

Sources

“Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door,” written and performed by Bob Dylan, was released on Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, July 1973.

Primary

- Pete Cobun, “University Issues Unrest Study,” Crimson-White, Sept. 14, 1970, pg 1.

- John Croft, “May’s Demonstrators Ask: ‘Why Did I Get Involved?’,” Crimson-White, Sept. 17, 1970, pg 1.

- Pete Cobun, “Blacks Occupy President’s Office,” Crimson-White, Apr. 22, 1971, pg. 1.

- Pete Cobun, “UA Blacks Continue Protests in Second-Week Demonstrations,” Crimson-White, Apr. 29, 1971, pg. 1.

- Nathan Turner, “Students Rally in Support of Union Strikers,” Crimson-White, Sept. 18, 1972, pg. 1.

- Harriet Swift, “Strike Rally Precedes Game,” Crimson-White, Sept. 29, 1972, pg. 1.

- Harriet Swift, “Students Dump Trash on 2nd Floor Rose,” Crimson-White, Oct. 9, 1972, pg. 1.