Woman suffrage was a factor in local and state elections across the country in the mid to late 1910s.

After the U.S. Congress passed the Nineteenth Amendment in July 1919, states began to vote on its ratification. It would take 36 states voting in favor to lead to its certification, and by the end of the year, there were already 22.

Alabama, which voted in September, was not one of them.

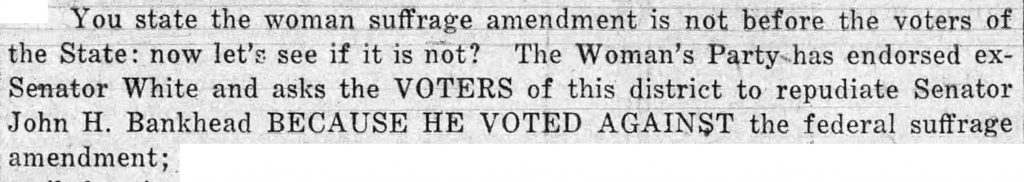

Martin L. Calhoun, “Woman’s Suffrage Is Before the Voters” [letter to the editor], Selma Times-Journal, Aug. 6, 1918.

This letter rebuts the idea that woman suffrage isn’t up for a vote in this election cycle. Calhoun, writing on behalf of the Alabama Male Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, gives examples of how it is being used by members of both national suffrage groups as a pressure point anyway.

Among the politicians mentioned, both current Senator John H. Bankhead and former Senator Francis S. White were Confederate veterans who participated in Reconstruction-era state politics before serving in the U.S. Congress. (White, it should be noted, was not actually running in the election.)

Joseph W. Green, mentioned later in the letter, was the state representative responsible for introducing a woman suffrage bill in the state legislature. He eventually repudiated it, earning him the ire of Alabama suffragists.

Militant Means

Through the 19th century NWSA was somewhat radical, compared with their counterparts of the AWSA. But their insistence and occasional civil disobedience was nothing compared to the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage, a splinter group which later transformed into the National Woman’s Party.

Under former NAWSA members Alice Paul and Lucy Burns in 1913, it took a much harder line and had a more confrontational approach.

If the South was uneasy with women even asking for the right to vote, it was decidedly opposed to this new militant approach.

“To ‘Picket’ White House: Women Suffragists Making Plans to Retaliate on President Wilson with ‘Silent Sentinels,’” Choctaw Advocate (Butler), Jan. 17, 1917.

This article highlights how militant suffrage activity in Washington, D.C., was viewed by the public, in this case, in a wire article published in an Alabama newspaper.

The Silent Sentinels was a coordinated protest campaign by the National Woman’s Party. From January 1917 to June 1919, members drew public attention to Wilson’s lack of support for suffrage by picketing in front of the White House.

Many picketers were arrested over the years, notably those sent to the Occoquan Workhouse, a prison for nonviolent offenders, in the summer of 1917; after a long a hunger strike, they were beaten in what is known as the Night of Terror.

Sue White, “’Militant’ Suffragists and What They Have Done” [editorial, reprinted from The Suffragist], Montgomery Times, Sept. 20, 1919.

This article describes recent activities of the National Woman’s Party, including a series of demonstrations in Washington, D.C., at Lafayette Park. Its writer, Sue Shelton White, was a Tennessee suffragist, formerly of NAWSA but by this point firmly converted to the more radical approach of the NWP.

She argues that Wilson should be getting the Southern members of his party in line rather than offering empty sympathy to the suffragists. Even at the national level, the South was an important factor in the debate.

Open letter from Carrie Chapman Catt, July 13, 1917, published as “Suffrage Association Again Disavows Militant Group,” Selma Times, July 18, 1917.

This letter from the National American Woman Suffrage Association shows a divide in the movement. Catt expresses NAWSA’s disapproval of the more radical approach of the NWP. The letter was undersigned by the Alabama Equal Rights Association, the state’s NAWSA chapter, signaling their alignment with its more conservative attitudes and methods.

Overall, the divide of the woman suffrage movement in the U.S. mirrored the situation in the U.K. Its National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), led by Millicent Fawcett, was the older, more conservative group, focused on peaceful and legal protest. Those advocating a more militant, radical approach joined the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), led by former NUWSS member Emmeline Pankhurst.

Catt was not exaggerating the influence of the U.K. on the movement in the U.S.: future American suffrage leaders Lucy Burns and Alice Paul learned tactics of direct action and civil disobedience during their time living in England and working with the WSPU.

In Alabama

Both the pro-suffrage and anti-ratification advocates in Alabama set their sights on members of the Democratic party.

Pattie Ruffner Jacobs, “Democrats Attention!” [editorial], Wilcox Progressive Era (Camden), July 10, 1919.

The Democratic party is committed to suffrage by federal amendment. The Democratic National Committee, the Democratic Congressional Committee, have passed strong resolutions in favor of the federal suffrage amendment.

In a public letter to fellow Democrats in the state, Pattie Ruffner Jacobs — a past president of the Alabama Equal Rights Association — does not offer extensive arguments in favor of woman suffrage. She simply warns that members nationally are watching those in the South to see if they will “break faith with the party” or vote to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.

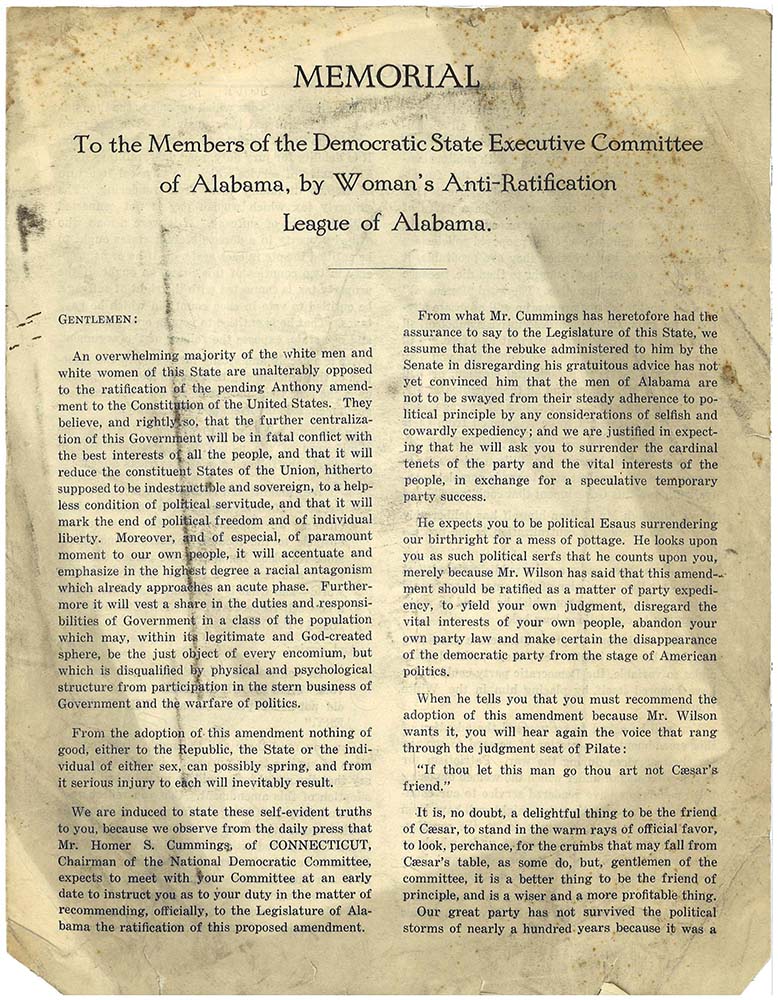

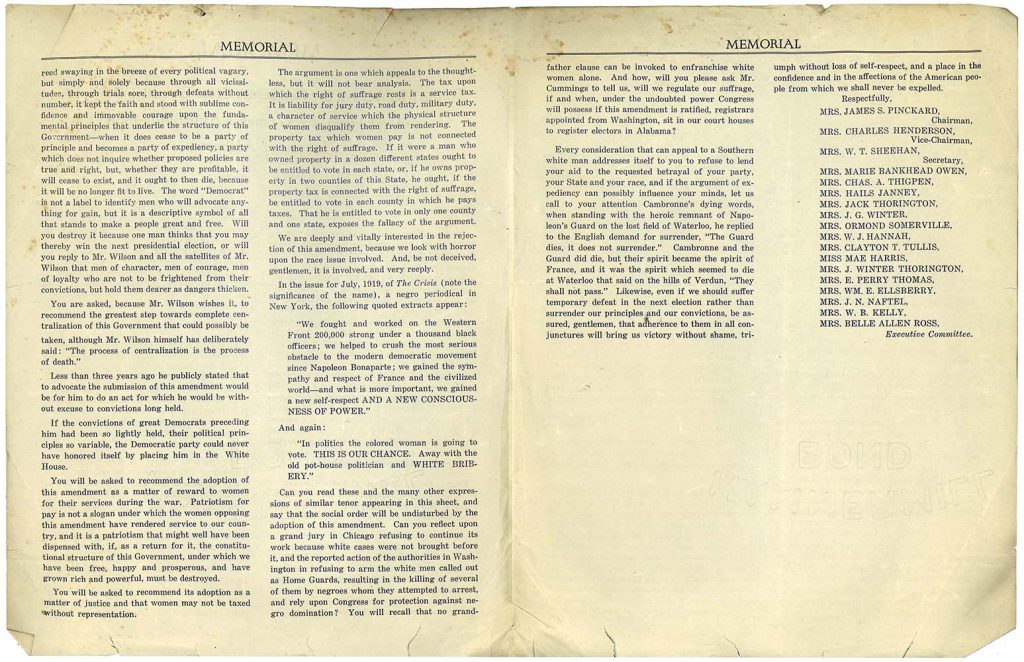

Woman’s Anti-Ratification League of Alabama, “Memorial to the Members of the Democratic State Executive Committee of Alabama,” c. 1919 (Hoole Broadsides Collection).

Every consideration that can appeal to a Southern white man addresses itself to you to refuse to lend your aid to the requested betrayal of your party, your State and your race, and if the argument of expediency can possibly influence your minds, let us call to your attention Cambronne’s dying words, when standing with the heroic remnant of Napoleon’s Guard on the lost field of Waterloo, he replied to the English demand for surrender, “The Guard dies, it does not surrender.”

The conclusion of the Anti-Ratification League circular makes a romantic analogy to the Napoleonic Wars (and later an allusion to the current Great War!) to convince its readers — explicitly, white men — that supporting the Nineteenth Amendment was treasonous, a form of surrender.

It was undersigned by the leadership of the group, including its president, Montgomery native Nina Winter Pinckard. She and the Alabama league became well known throughout the South, especially during the ratification battle in Tennessee, which in 1920 would become the last state necessary to certify the amendment.

Nina was better known by her married name, Mrs. James S. Pinckard, which was likely strategic. Though most married women in the South still frequently used their husbands’ names — including, at times, Pattie (Mrs. Solon) Jacobs — Pinckard used this form exclusively, such that it was actually quite difficult to uncover her first and maiden names.

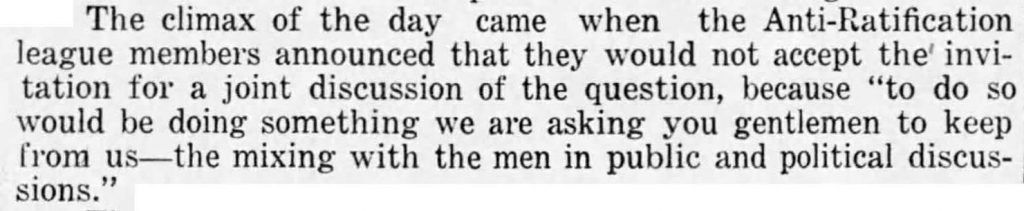

“Greatest Suffrage Fight in History Put on Wednesday Morning,” Montgomery Times, July 16, 1919.

The meeting was replete with humor and pathos, the women having divided themselves into two different associations with two different ideas about the question of women voting.

The suffragettes took charge of the halls, galleries and the main assembly room of the representatives.

Long before the meeting was called, about 10:30 o’clock, scores of men and women were wearing the yellow emblem of the suffragettes.

There were, of course, many antis there, but by far the larger majority of the women wore the suffrage emblem.

This article describes a public debate over woman suffrage in the Alabama legislature. In particular, it shows the difficult — and ironic — position of the “antis”:

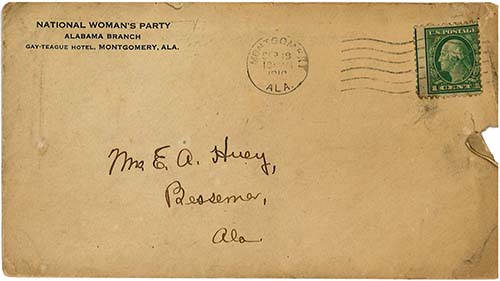

Letter from Sue S. White and the National Woman’s Party in Alabama, Sept. 18, 1919 (Collection on Women in Alabama).

The failure of the Alabama Legislature to ratify the suffrage amendment is not a suffrage defeat, as Alabama has never been counted among the states expected to ratify. A non-partisan policy, however, demands encouragement of every effort for ratification, however weak and ineffectual and half-hearted the effort may be.

Ultimately, Alabama voted not to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment in September 1919.

This form letter, sent to a Bessemer woman, indicates the National Woman’s Party didn’t anticipate Alabama voting in favor of the Nineteenth Amendment. However, that did not mean they had given up the fight.

For brief primary accounts of ratification in Alabama, see the following histories, the first from the NWP and the second from NAWSA:

Inez Haynes Gillmore, The Story of the Woman’s Party, New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1921, pg. 422+.

Ida Husted Harper, The History of Woman Suffrage, vol. 6, N.Y.: J. J. Little and Ives Co., 1922, pg. 7+.