While Alabama did not have a long history with woman suffrage advocacy, it had a longer history than you might guess! Read the narrative below to learn more.

Note: In addition to the primary sources mentioned below, this draws on secondary sources, especially various entries in the Encyclopedia of Alabama and Mary Martha Thomas’s The New Woman in Alabama (see section Scholarly Sources on the Resources page).

Early Efforts at Organization

The first suffrage club in Alabama formed in 1892 in New Decatur (now part of Decatur), a town in north Alabama near Huntsville. It had seven members. That same year, another club was formed in Verbena, a town in central Alabama, with five founding members.

The first statewide organization, the Alabama Woman Suffrage Organization, was formed in 1893. Ellen Stephens Hildreth of New Decatur, a journalist and wife of the local newspaper editor, served as president; and Frances Griffin of Verbena, a former schoolteacher, was the secretary. Griffin became a well-known speaker in the region. Another prominent leader of the movement in Alabama was Virginia Clay Clopton, elected president of the state organization in 1896.

These groups, both local and statewide, did not gain much traction, due in part to the economic depression of the mid-late 1890s. But the real problem was social and philosophical: those in power in the South just weren’t ready to entertain the possibility. Nevertheless, these women were spurred by the desire to enact social reform to keep trying.

For more on the early movement in Alabama, see

Susan B. Anthony and Ida Husted Harper, History of Woman Suffrage, vol. 4 (1902), pg. 465-469.

Alabama Equal Suffrage Association (AESA)

1912 – Founding

The Alabama Equal Suffrage Association (AESA) began as a joint effort between similar groups in Selma and Birmingham. It quickly allied itself to NAWSA, at the time the only large national organization.

Birmingham leader Pattie Ruffner Jacobs was its first president. She had been inspired to act for change after hearing well-known social reformer Jane Addams speak in 1911. Later that year, the Birmingham Equal Suffrage Association was established. It second president was Bossie O’Brien Hundley, whose husband was a judge and a prominent Progressive.

Selma’s group was established the year before by Mary Winslow Partridge. A later leader from Selma, Hattie Hooker Wilkins, also had a major role in the state organization. She went on to be the first woman elected to the state legislature, in 1922.

The toil of promoting equal and exact justice, of improving civic, social, economic, educational and sanitary conditions in Alabama, and of mitigating the cruelties of industrialization — this toil falls heavily upon the men, when it falls heavily on men alone. The vote will enable the women to share this burden. It will bring to fruit the seed of democracy sown by our forefathers, when they declared taxation without representation is tyranny. It will protect the home. It will conserve the race.

This part of the organization’s founding document indicates the unique position of Southern suffragists. They were attempting to appeal to traditional notions of morality and a long-held attitude of racial superiority while at the same time declaring that it was time for women to be treated equally in terms of citizenship.

But they still faced an uphill battle merely from a social standpoint: people did not expect good Southern women to be so outspoken, especially about politics.

1913 – Establishing Goals

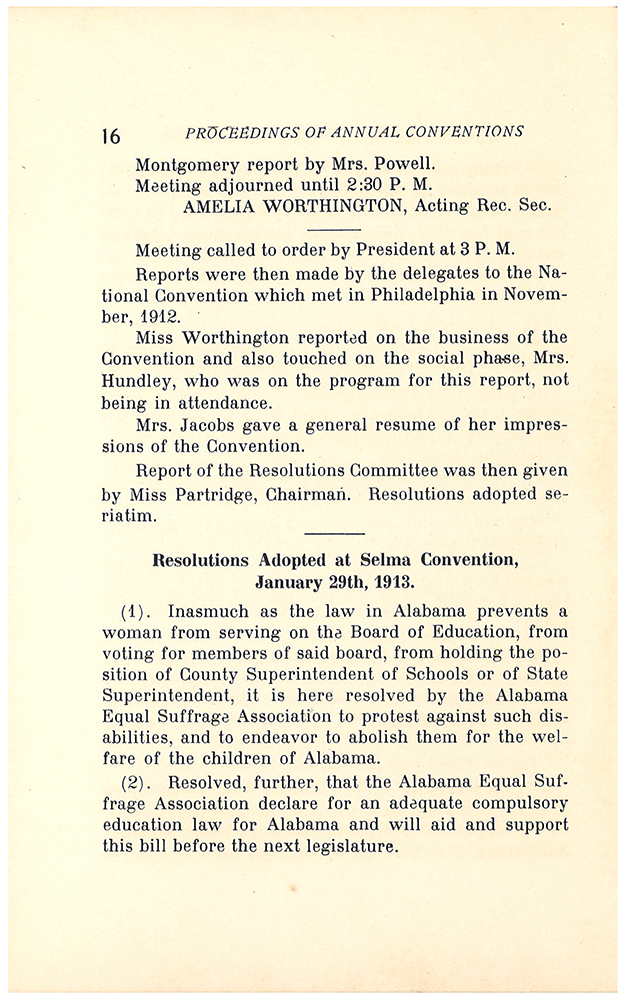

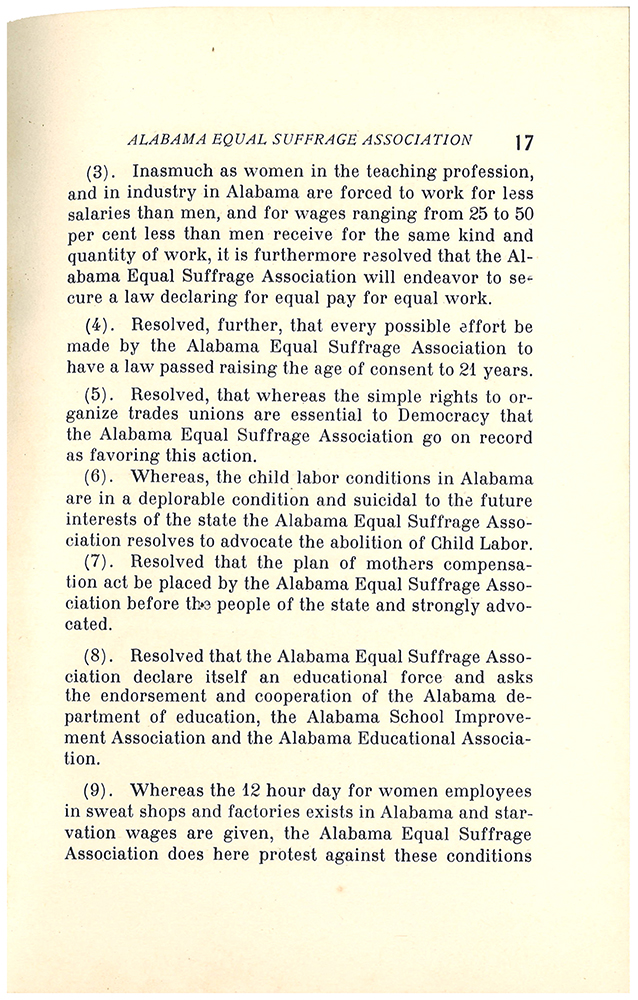

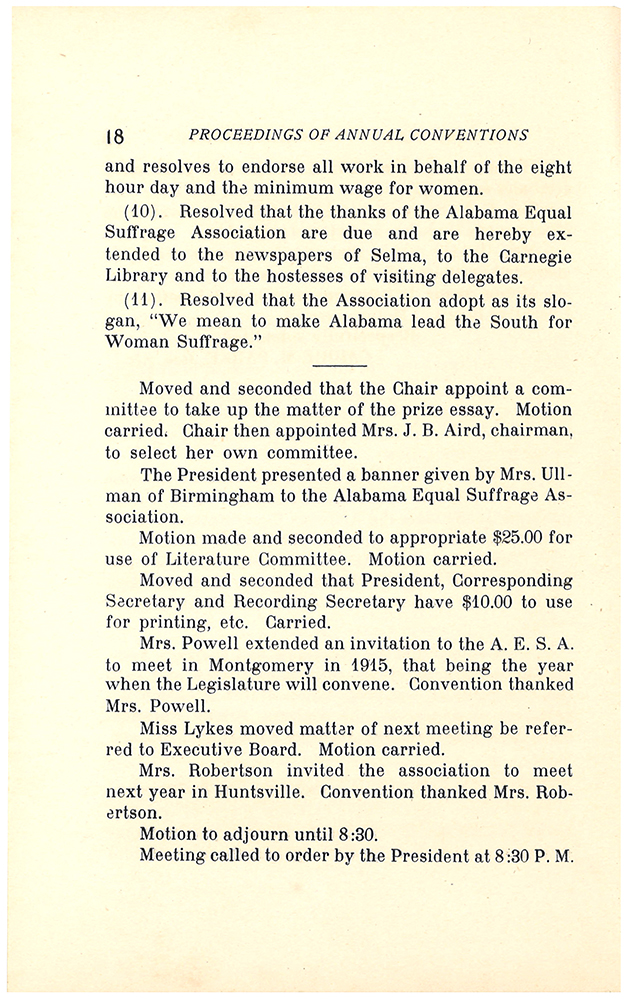

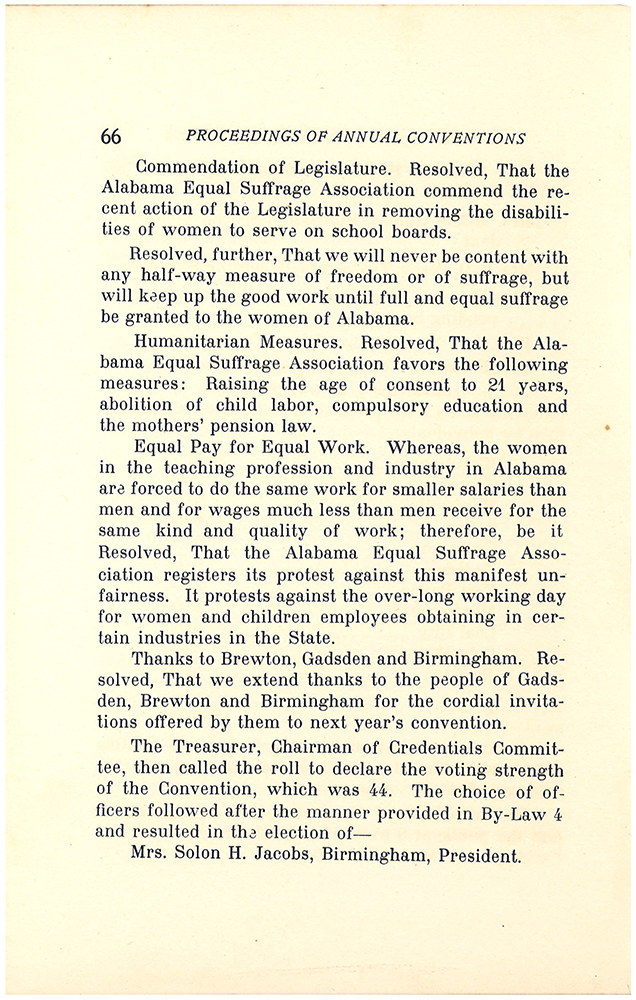

AESA had its first convention in Selma in 1913.

The group’s first set of resolutions highlight its broad range of concerns, from the education and welfare of children to equal pay and better conditions for working class women.

1914 – Taking Stock

The 1914 convention was held in Huntsville.

In her President’s Report that year, Jacobs describes the state of the movement:

Our progress has been phenomenal in many respects. In spite of our own inexperience, our lack of organization methods, our empty treasury, our little comprehension of team work — all our manifold mistakes, we are to be congratulated.

She covers several topics:

- Formation of the AESA on October 9, 1912, explanation of preliminary meetings, and membership of the group in NAWSA.

- Growth of the movement in Alabama from four local groups to eleven, and more that just need help organizing.

- The problem of “unorganized suffrage sentiment,” which is not visible to the public.

- A focus on disseminating literature and contributing to the press — educational means of “uprooting ignorance of what the equal suffrage movement really is.”

- Visits from suffragists from the national organization, including Jeannette Rankin, who would later become the first woman to serve in the U.S. Congress.

- Recommendations for the future, including creation of a ways and means committee and focusing of the legislative committee on reaching candidates for office.

- Jacobs’s activities, especially visiting local groups and traveling to out-of-state conferences.

Her report also makes clear that the group is open to all, along social, political, and even gender lines. Notably, she does not mention race.

1915 – Shifting Gears

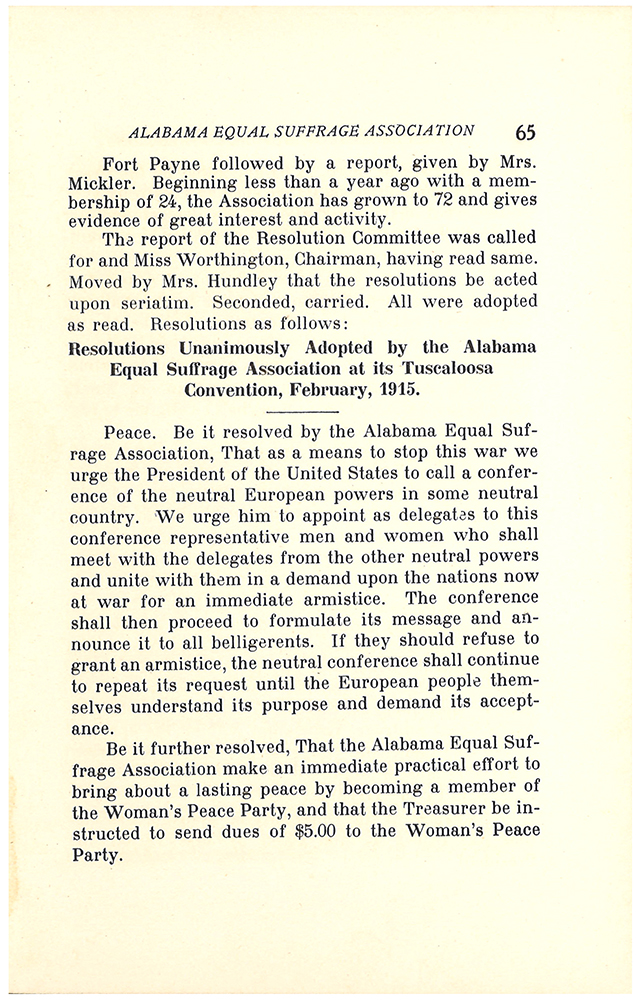

The group met in Tuscaloosa in 1915.

The group’s 1915 resolutions immediately indicate the different world the women were now living in. The first is a call for peace, as the Great War had already begun in Europe. The organization also resolves to join the Woman’s Peace Party. The rest then address familiar social welfare topics.

In her President’s Report that year, Jacobs highlights the gains made nationally, including suffrage measures passed in Tennessee and West Virginia. She also mentions the failed U.S. Congressional votes of 1915 and how Southern suffragists can counter state’s rights sentiment. Their plan: to bring a bill before the state legislature asking lawmakers to submit woman suffrage to a general vote, which would indicate what the state’s citizens wanted for itself.

She also discusses several other topics:

- The participation of 14 Alabama delegates in the national convention in Nashville; and the decision of the Southern delegates to focus on Alabama as “most hopeful of immediate legislative results”

- The help, logistical and financial, of other Southern suffragists, including Laura Clay of Kentucky and Kate Gordon of Louisiana (both leaders within the breakaway Southern States Woman Suffrage Conference)

- The growth of the movement in Alabama to 41 local associations

- Jacobs’s activities as president

- Recommendations, including new standing committees for publicity, a traveling library, and church extension

In conjunction with the convention this year, NAWSA leader Dr. Anna Howard Shaw gave a public speech on woman suffrage, which was covered in detail in a newspaper article. It was summed up as a success:

Shaw described the country as an “aristocracy” rather than a democracy:

We claim to have a republican form of government, but we have never been a republic and are not now. We are merely evolving a republic out of a monarchy.

A republic is defined as a country governed by the people. But the laws of Alabama are not made by lawmakers elected by the people, but by only half of them.

Shaw was also well aware of her audience, playing upon regional patriotism:

There are no women who have ever paid a dearer price for their freedom than the women of the south. I know and you know and some day history will tell to the world that the traditions of the south were maintained by the women. They bore their hardship with fortitude never before dreamed of. In putting the ballot into the hands of the women, you are giving it to the daughters of the women who so bravely acquitted themselves.

Her speech was not without moments of humor. The article reports that a group of students “gave her a yell” as she took to the podium. Her reply?

Thank you boys. Our hope is in the boys. It’s no use to deal with a man over 40.

Later Activities

By the time the United States entered World War I, much suffrage activity in the South and elsewhere took a back seat to support of the war effort.

However, it did not stop entirely. During the 1918 meeting, the following resolution was passed:

Whereas, the Senate will soon vote on the Federal Suffrage Amendment, therefore, be it resolved, by the suffragists of Alabama assembled in their sixth annual convention, that the U. S. Senators, John H. Bankhead and Oscar W. Underwood, be, and they hereby are, earnestly petitioned to forward the march of democracy, to carry out the policy of the Democratic administration and to represent truly the wishes of the women of their own State by supporting this amendment and voting for it when it comes up in the Senate

For an account of AESA activities after 1915, including conventions of 1916, 1917, and 1918, see

Ida Husted Harper, History of Woman Suffrage, vol. 6 (1922), pg. 1-9.

Alabamians & the National Organizations

NAWSA

After the failure of the suffrage bill in the Alabama legislature in 1915, Jacobs turned her attention to supporting the National American Women Suffrage Association’s broader aims. She had tried the “states’ rights” approach; now she and AESA would advocate for a federal amendment.

But Jacobs was no newcomer to NAWSA, having been a delegate from Alabama at the 1913 and 1915 national conventions.

In 1913, she was chosen to give the national body’s response to the greetings of leaders Nina Allender and Alice Paul.

The 1913 meeting is discussed in

Ida Husted Harper, History of Woman Suffrage, vol. 5 (1922), pg. 354-397. [See pg. 365 for mention of Jacobs.]

In 1915, as a vote on the amendment loomed in the U.S. legislature, she spoke to the Senate. As one might expect from a white Southern suffragist, she was simultaneously progressive about gender and retrogressive about race.

She addressed the “states’ rights” arguments of reluctant Southern senators, openly recognizing them as concerns about race. They were concerns she understood and sympathized with:

If this amendment is adopted it in no wise regulates or interferes with any existing qualification for voting (except sex) which the various State constitutions now exact. It leaves all others to be determined by the various States through their constitutional agencies. It is a fallacy to contend that to prohibit discrimination on account of sex would involve the race problem. The actual application of the principle in the South would be to enfranchise a very large number of white women and the same sort of negro women as of negro men now permitted to exercise the privilege

However, she also challenged traditionalism about gender directly:

However much these chivalrous gentlemen may wish it were so, that southern women might truly be called roses and lilies which toil not, they must know that their compliments do not provide equal pay for equal service, which obtains in all the woman suffrage States and that their flowers of speech do not help us secure a co-guardianship law, which every suffrage State has and which is non-existent in all southern States. The pedestal platitude appeals less and less to the intelligence of southern women, who are learning in increasing numbers that the assertion that they are too good, too noble, too pure to vote, in reality brands them as incompetents.

The 1915 meeting is discussed in

Ida Husted Harper, History of Woman Suffrage, vol. 5 (1922), pg. 439-479. [See pg. 463+ for excerpts from Jacobs’s speech.]

NWP

The more radical National Woman’s Party had a smaller profile in Alabama than NAWSA.

The Alabama branch was led by Sara Haardt, a future English professor and author. As was typically the case with NWP members, she was far younger than her AESA/NAWSA counterparts, just 21 years old when the amendment was voted on. (Jacobs and Wilkins, for example, were both in their mid-forties.)

Ironically, Haardt later married the much older critic and scholar H. L. Mencken, who had been famously mocking of militant suffragists (see In Defense of Women, 1918):

The iron-faced suffragist propagandist, if she gets a man at all, must get one wholly without sentimental experience. If he has any, her crude manoeuvres make him laugh and he is repelled by her lack of pulchritude and amiability. All such suffragists (save a few miraculous beauties) marry ninth-rate men when they marry at all. They have to put up with the sort of castoffs who are almost ready to fall in love with lady physicists, embryologists, and embalmers

By his reckoning, either Haardt was one of those “miraculous beauties” or he was among those “ninth-rate men.”

For an example of NWP’s interest in Alabama, see

“National Democratic Committee Takes Further Action in Alabama: Is Alabama Waking Up?,” The Suffragist, Aug. 23, 1919, pg. 5.

African American Women

Like their counterparts in the rest of the country, African American women in the South were less likely to have organizations devoted solely to suffrage, instead working on these aims within the structure of women’s civic groups like the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs.

Many of the nationally prominent voices for Black female suffrage came from outside the South, but two notable Southern African American suffragists have strong Alabama connections, via their work at the Tuskegee Institute:

Margaret Murray Washington (c. 1865-1925) was born in Mississippi to sharecroppers, her father a white Irishman and her mother an African American. After attending Fisk College, she came to Tuskegee to be its “Lady Principal” — and to marry its founder, Booker T. Washington. In addition to being instrumental in her husband’s speaking career, she pursued her own goal of uplifting and educating Black women, forming the Tuskegee Women’s Club and co-founding the National Association of Colored Women. She was a teacher and activist, regularly speaking on topics like prison reform and anti-lynching.

Adella Hunt Logan (1863-1915) was born in Georgia to a free woman of color and a white plantation owner. She was at Tuskegee from 1883 to her death, serving as its first librarian and teaching English and social sciences. As an advocate for universal suffrage, she was active in the Tuskegee Woman’s Club, lectured widely for the National Association of Colored Women, and contributed articles to NAWSA’s The Woman’s Journal and the NAACP’s Crisis.

Other notable Black suffragists spent time teaching at Tuskegee, including Josephine Bruce and Hallie Quinn Brown.