The Usual Stumbling Block

For many white Southerners, the idea of granting women suffrage seemed to threaten an entire way of life.

The outlook that prevented women from being full citizens came from a similar place as paternalism about race, which should have made Black women and white women allies. White Southern suffragists, however, often didn’t see it that way.

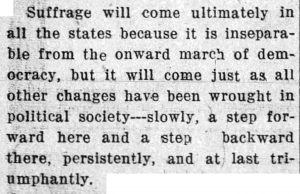

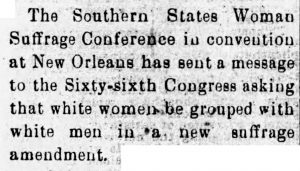

“The Impatient Suffragists,” Selma Times, July 6, 1916.

The writer’s main concern was something shared by Americans in other regions, notably in the Northeast and Midwest, where few states had passed woman suffrage laws: society was changing too fast. However, the writer does not seem to be anti-suffrage, praising the movement’s success in winning both major parties to the cause.

But just because party leaders were on board, that did not mean the Southern branches of these parties were prepared to play along.

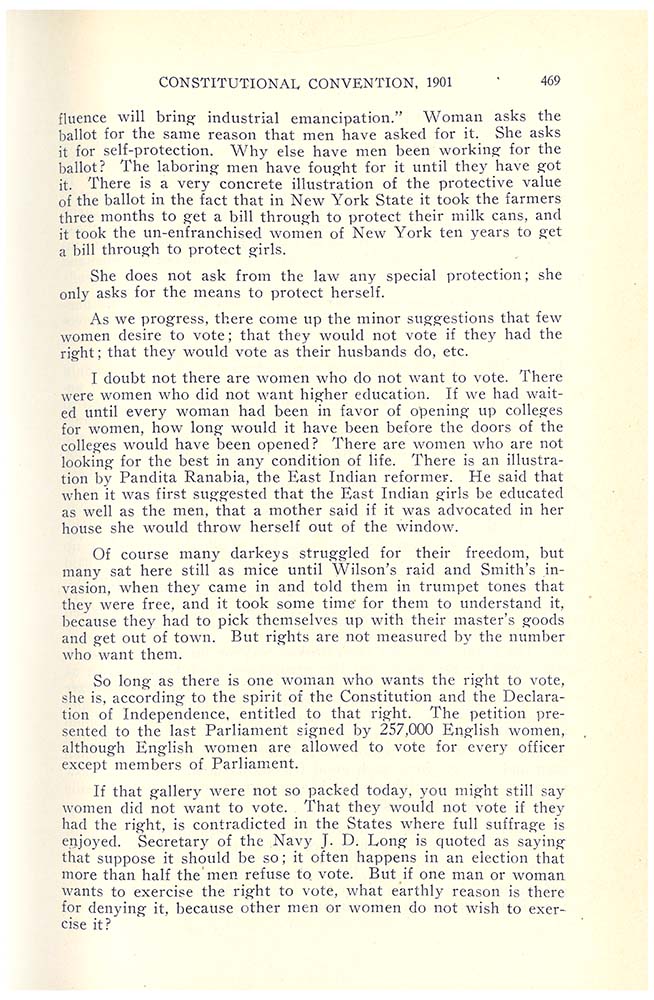

Address of Frances Griffin, June 10, 1901, recorded in Proceedings of the Constitutional Convention, vol. 1

I doubt not there are women who do not want to vote. There were women who did not want higher education. … Of course many darkeys struggled for their freedom, but many sat here still as mice until Wilson’s raid and Smith’s invasion…

Woman suffrage was not really up for debate during the Alabama Constitutional Convention of 1901. Frances Griffin, an early Alabama suffrage leader, was likely allowed to speak out of simple courtesy.

What was up for debate: how to disenfranchise African American voters without technically running counter to the Fifteenth Amendment. It is clear that, despite her progressive stance on women’s rights, Griffin was welcome at the convention because she had a typically racist view of non-whites. She was not an outlier among white Southern suffragists.

You can read the entire text of Griffin’s speech at the Alabama Department of Archives & History.

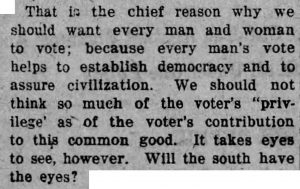

William Pickens, “Colored Woman Suffrage” [editorial], Voice of the People (Birmingham), June 12, 1920.

This editorial in an African American newspaper argues that Black women could contribute to the “common good” but wonders if the male voters of the South will see things the same way.

William Pickens was an African American speaker and writer, and his editorials were syndicated in Black newspapers across the country. He was also a Southerner, born in South Carolina to former slaves and raised in Arkansas. Among other places, he studied at Talladega College in Alabama.

As a African American Southerner, Pickens discusses the complexity of the issue in honest historical context:

We always fear those most whom we most wrong. There is a large element in the south which will naturally fear colored women, — even when they come with gifts of helpfulness. We always think of those we wrong as coming in to avenge their wrongs rather than to aid us. That is a part of our self-punishment for doing the wrongs we do.

States’ Rights

For many Southerners, the campaign for a federal woman suffrage amendment was a direct threat to state sovereignty.

Rather than ending with the Civil War, the desire to maintain states’ rights continued into the twentieth century. The region still resented the sweeping changes imposed upon it by the federal government during Reconstruction (1863-1877).

As had been the case during the sectional crisis before the war, the most prominent “rights” being clung to were about maintaining the status quo in race relations.

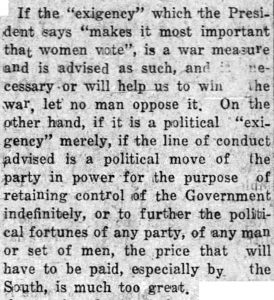

J. B. Evans, “Prohibition, States Rights & Suffrage” [letter to the editor], Selma Times-Journal, Jan. 14, 1918.

Evans’s letter to the editor addresses Southern concern over federal laws regarding alcohol and woman suffrage. He argues that wartime “sacrifice” of states’ rights over these areas is dangerous.

Before this passage, he reveals his ultimate fear, that federal intervention will lead to a more rights for African Americans:

This contention of yours carried to its logical conclusion, would justify New York in saying inasmuch as New York has adopted Woman Suffrage, the aid of the Federal Government should be invoked to compel Alabama to confer suffrage on all her white and black women, — whether Alabama likes it or not.

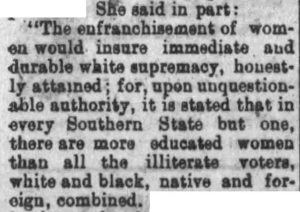

“Woman Suffrage in the South,” Tuskegee News, May 21, 1903.

This report of the keynote speech at the 1903 National American Woman Suffrage Association conference repeats a common argument used in the South: that woman suffrage will help maintain white supremacy.

Belle Kearney, the speaker, was born into a slave-owning family in Mississippi and was an ardent white supremacist. Despite these views, she was a lobbyist for NAWSA. As the South became more and more important in the suffrage fight, NAWSA became increasingly willing to focus on white woman suffrage and to condone racist arguments in its favor.

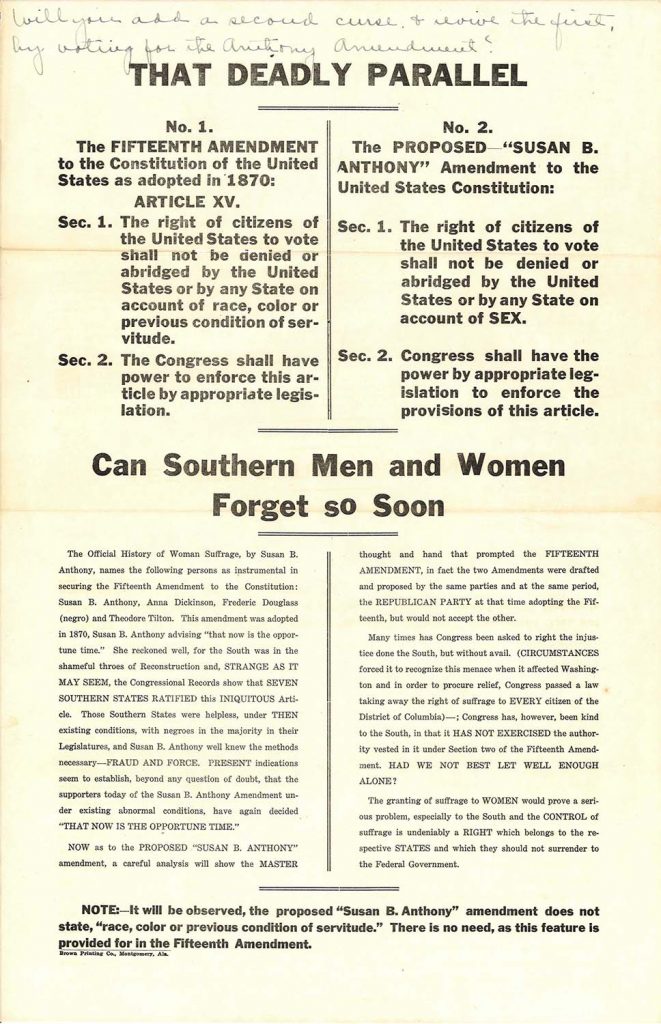

“That Deadly Parallel,” printed in Montgomery, Ala., c. 1918 (Hoole Broadsides Collection).

Congress has, however, been kind to the South, in that it HAS NOT EXERCISED the authority vested in it under Section two of the Fifteenth Amendment. HAD WE NOT BEST LET WELL ENOUGH ALONE?

This circular attempts to scare readers by visually comparing the Nineteenth Amendment (then called the Susan B. Anthony Amendment) to the Fifteenth Amendment, which granted Black male suffrage. Its rhetoric is hard to follow, but that may be by design — the point is to agitate anger about a potential loss of “states’ rights.”

“A Bad Situation” [reprinted from Selma Journal], Cherokee Harmonizer (Centre), June 12, 1919.

This article highlights a proposal from Southern suffragists explicitly aimed at preventing Black women from getting the vote. It goes on to draw direct parallels between woman suffrage and African American suffrage:

The Conference opposed the Anthony Amendment as grouping white women with negroes, exactly as the fifteenth amendment grouped white and negro male voters until the Southern States by state regulation solved the problem.

The Southern States Woman Suffrage Conference, whose meeting is discussed here, broke off from the National American Woman Suffrage Association in 1906 due to its desire to focus on white woman suffrage and state-level legislation.