Note: You can click on any of the thumbnail images below to view a larger version.

Suffragists vs. Antis

It surprises most people to learn that many women were not in favor of having the right to vote. These “Antis,” as they were called, were often just as intelligent and enterprising as their suffragist counterparts, advancing clear and logical arguments to support their claims. Ultimately, however, these arguments were based on an outmoded view of women’s role in society.

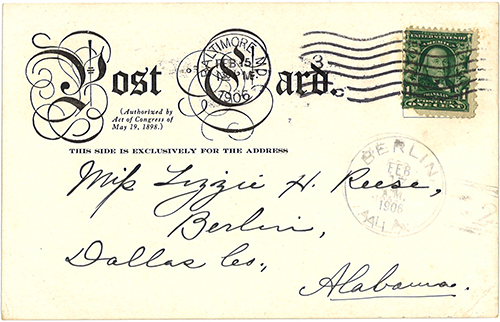

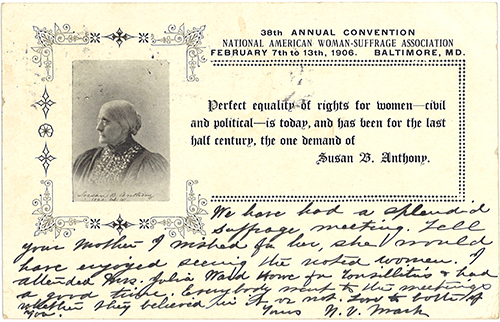

Postcard from N. V. Mark, Baltimore, Md., to Lizzie H. Reese, Berlin, Ala., Feb. 1906 (Hoole Postcard Collection).

We have had a splendid suffrage meeting. Tell your mother I wished for her, she would have enjoyed seeing the noted women. I attended Mrs. Julia Ward Howe for tonsillitis & had a good time. Everybody went to the meetings whether they believed in it or not.

This note to an Alabama woman from a friend attending the 1906 NAWSA convention suggests that such events were long seen as important times of gathering and debate on women’s issues — whatever one’s stance on the suffrage question.

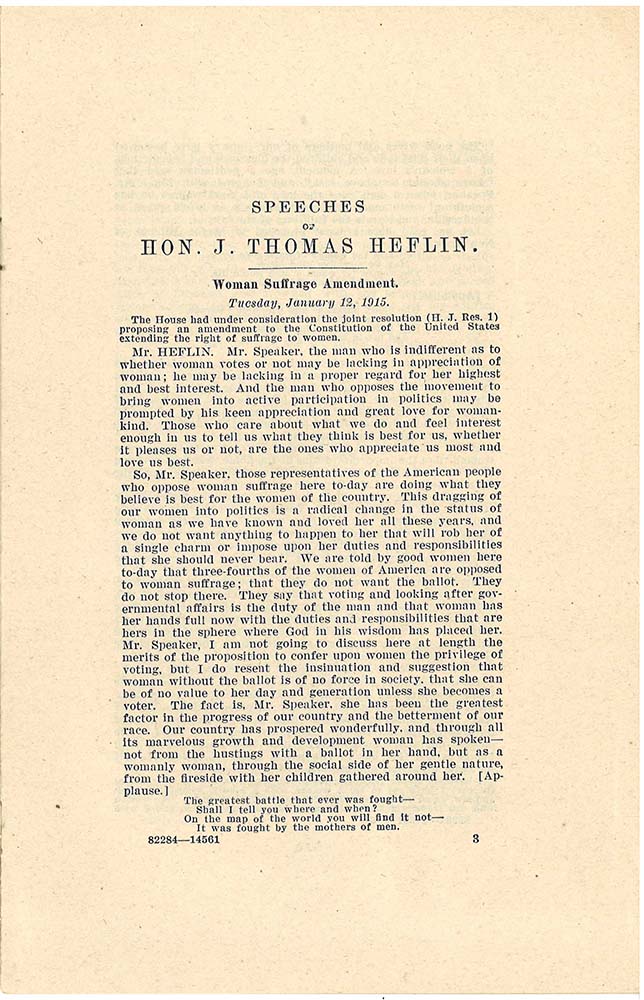

These speeches by U.S. Representatives from Alabama are philosophically opposed, but they advocate for the same outcome, politically.

James Thomas Heflin, “Woman Suffrage Amendment,” U.S. House of Representatives, Jan. 12, 1915

So, Mr. Speaker, those representatives of the American people who oppose woman suffrage here to-day are doing what they believe is best for the women of this country.

“Cotton Tom” Heflin argues that opposing suffrage is about having a woman’s “highest and best interest” at heart. Fearful of “radical change,” he is concerned that voting would be a burdensome duty and somehow make women less charming. He is adamantly against a federal amendment.

John W. Abercrombie, speech on the woman suffrage amendment, U.S. House of Representatives, Jan. 12, 1915

If it be claimed that the majority of women do not desire the ballot and would not vote, I answer that right and justice can not be estimated in numbers…

John Abercrombie, on the other hand, uses most of the his speech to counter several common objections about woman suffrage. However, despite his apparent support on principle, Abercrombie is like most Southern politicians of the time: he views the issue as one for the states to decide, so he will not support a federal amendment.

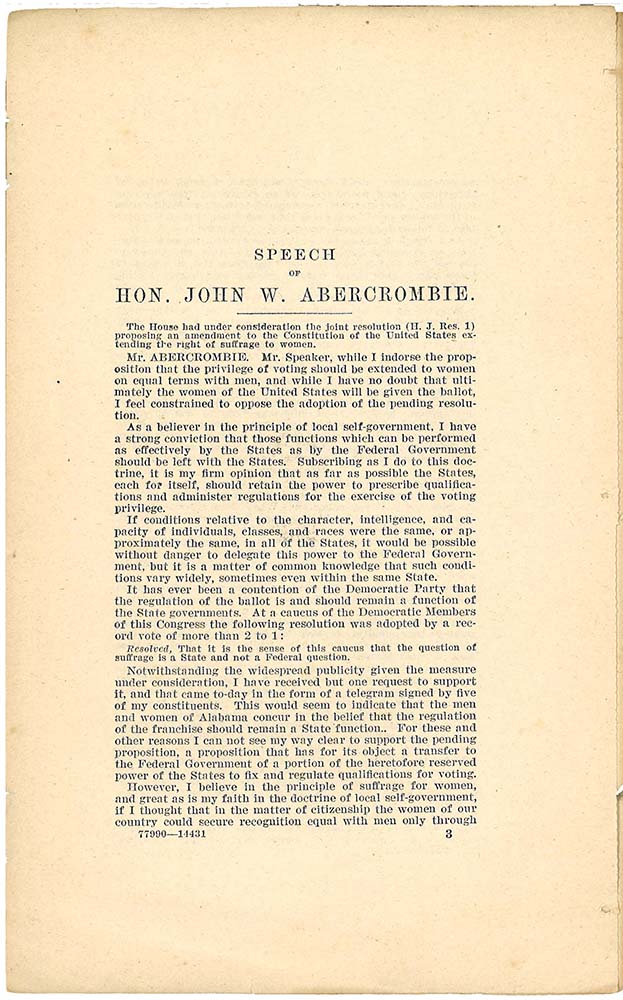

Arthur Collins Maclay, Is Christianity Hostile to the Cause of Woman Suffrage?, 1913.

In appreciation of his manly attitude in opposing woman-suffrage.

The New England author of this anti-suffrage pamphlet inscribed a copy he sent to Alabama Rep. “Cotton Tom” Heflin, to recognize that he was an ally to the cause — an apparently very publicly visible one.

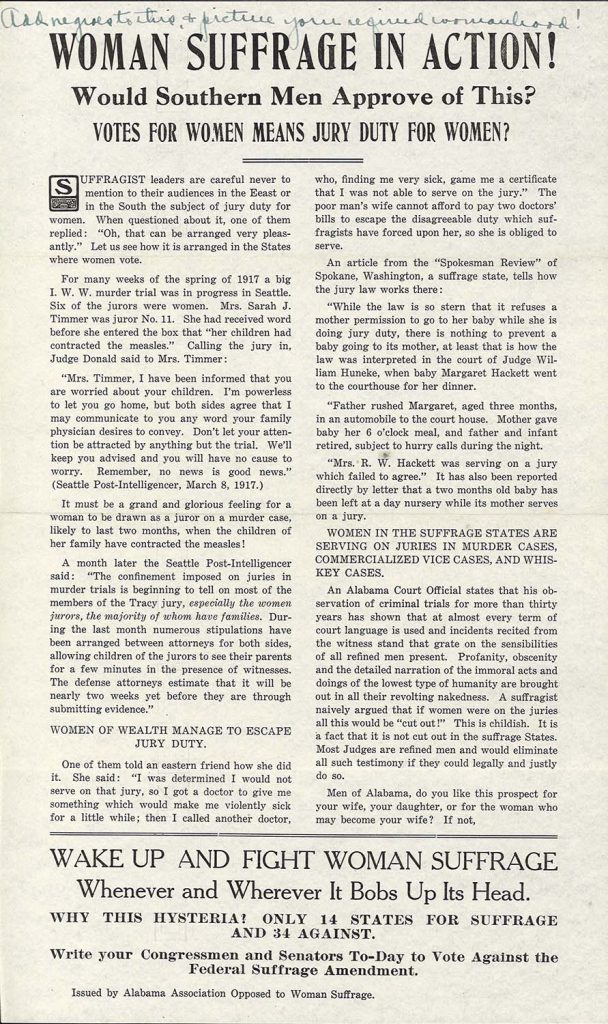

Alabama Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, “Woman Suffrage in Action!” c. 1918 (Hoole Broadsides Collection).

Men of Alabama, do you like this prospect for your wife, your daughter, or for the woman who may become your wife? If so,

WAKE UP AND FIGHT WOMAN SUFFRAGE Whenever and Wherever It Bobs Up Its Head.

This flier advances a common argument against granting woman suffrage: that voting leads to jury duty. It attempts to scare male readers by describing the realities of their loved ones serving on a jury, including hearing about all nature of vices and neglecting the care of children.

Opponents of woman suffrage often argued that those who cannot fight in wars in order to enforce laws should not be making them. Jury duty, tied to voting, was seen as another means of enforcement. Evidently by this time, this general argument no longer held water — after all, non-combatant men have long had the right to vote and otherwise participate in civic life — so this flier turned to using jury duty itself as its own kind of scare tactic.

Entanglements

The anti-suffrage movement was bound to fail in the face of two overwhelming realities of the 1910s: the temperance movement and World War I.

The desire to bring about prohibition of alcohol led many otherwise complacent women to push for the vote, as they were the important drivers of the temperance movement. In general, many women argued for the vote so as to tackle a range of social realities that hurt families, including alcoholism and child labor.

Meanwhile, World War I showed that women were capable of taking on new roles in society; suffrage could not be far behind.

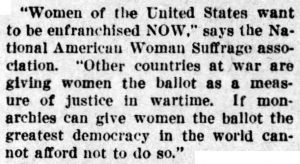

“’Woman Suffrage Very Largely a War Question,'” Albany-Decatur Daily, Aug. 20, 1917.

This article shows how the entry of the U.S. into World War I brings it in line with other world powers in more ways than one. Like their counterparts in the U.K., France, and Canada — whose representatives are all quoted here — American women are agitating for suffrage as a war measure.

Later that year, Canada enfranchised women serving in the military and female relatives of soldiers serving overseas. Wider woman suffrage came in 1918. Woman suffrage (with age and property restrictions) was granted in the U.K. in 1918 as well.

In France, however, woman suffrage was not granted until 1944, near the end of World War II.

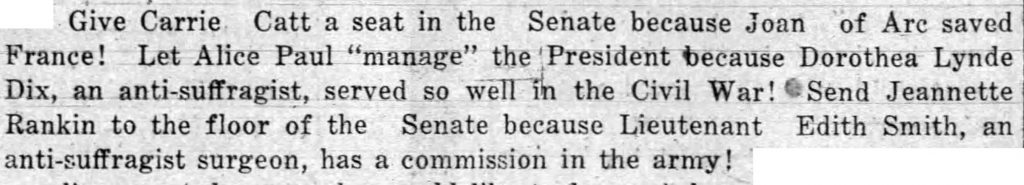

David Lawrence, “Women vs. Suffragists” [editorial], Selma Times-Journal, Aug. 6, 1918.

This article sarcastically points out the irony in suffragists arguing for the vote in wartime, given the anti-suffrage views of fellow women throughout history who actually spent time on the battlefield. Some of them were contemporaries, once again highlighting the dissonance between suffragists and Antis.

But maybe more to the point, Lawrence also asks them to stop saying women are “bearing the brunt of” World War I:

Even if it were true, the fact that “women” are doing so well without the vote would not establish either the need of the vote or the absurd implication that women can be paid in political coin for the loss of their husbands, fathers, sons or brothers!

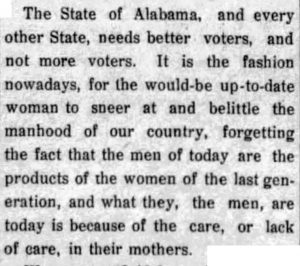

“Suffrage and Prohibition” [reprint of letter to the editor, Montgomery Times], Our Southern Home (Livingston), Feb. 10, 1915.

This letter to the editor written by an anonymous woman concerns the interplay of the temperance and suffrage movements. She claims the country doesn’t need woman suffrage to ensure prohibition laws are passed — women already have influence in society because they help shape the lives of the sons they raise.

The argument that women did not need to vote in order to have influence was an old one, and by this point it was largely considered refuted. Perhaps this is why the writer also leans on statistics:

…the only State in the Union which has both equal suffrage and prohibition is Kansas, and that State went “dry” before women were given the vote…