By: Evan Ward, University of Alabama M.A. student in History

Today, Evan Ward shares a selection from his research on changing attitudes toward industrial work in Alabama after the Civil War. If you are a graduate student working on resources from the Division of Special Collections and you would like to share a selection from your work on Cool@Hoole, please contact editor Amy Chen at ahchen@ua.edu.

Alabama, more than perhaps any former Confederate state, was suited for nineteenth century industry. “No place on earth, other than the Birmingham District,” writes historian W. David Lewis, “contained within a thirty-mile radius all three raw materials required for iron production.” [1] Those three raw materials were red and brown hematite, also known as iron ore; limestone, commonly used in smelting; and coal, used to fire the state’s blast furnaces. The state’s potential for industry was widely known, thanks to the many geological surveys that had been conducted throughout the pre-war and post war periods. Alabama’s industrial capacity had even been tested during the Civil War, an event that spurred the firing of new forges and the laying of new railroads. After the war, state industrialists and advocates for a ‘New South’ saw a bright future for Alabama, whose mineral resources would surely elevate her to the same status as northern industrial giants. They brashly named the state’s emerging industrial center Birmingham, after Britain’s main industrial hub. But, after the war, industrial development languished. Many iron forges and coal mines wrecked by Union forces were not reopened for years – and those that survived often struggled to stay in operation.

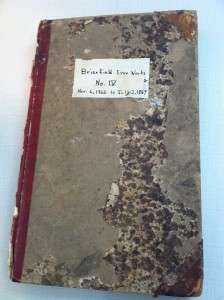

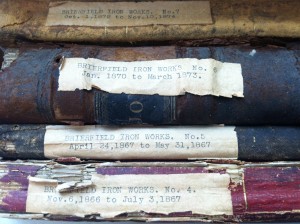

One such operation was the Brierfield Iron Works, located in Bibb County, Alabama. The site was initially developed in 1861, before being ruined by a Union raid in 1865. After the war, Brierfield was purchased and rebuilt by the Canebrake Company, who placed Josiah Gorgas in charge of the operation. The records of the company, housed in the Hoole Special Collections Library, reveal much about the day-to-day business that consumed Gorgas’s time and energy. His outgoing correspondence sheds an especially revealing light on the difficulties faced by Alabama’s early industrialists as they attempted to establish a foothold in a state whose economy had long been dominated by agricultural interests.

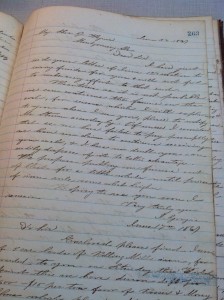

Though often seen as developing hand-in-hand with the coal and iron industries, Gorgas quickly found friction with Alabama’s railroad companies. Rail companies were charging increasingly high rates to transport iron and coal to larger markets, and Gorgas was disappointed that Alabama’s emerging industrialists could not better coordinate their efforts. In an 1867 letter to a colleague, he writes “there is a disposition to use our iron at St. Louis and also at New Orleans,” but that “this will be checked by the very high rates of freight charged from here to Selma.” He often advocated a more mutually beneficial relationship uniting railroad and materials companies, hoping that when it came to reducing freight, rail barons might “be induced to see the matter in its just light.”[2]

The irregularity of Alabama’s railroad practices posed an additional problem for Gorgas. The lack of a freight agent to verify deliveries of shipments constituted “a serious impediment in various ways, as a RxR receipt is frequently needed as a voucher for the shipment.”[3] His inability to make his industrial site a regular stop along an established railroad route was also a major inconvenience, as it hindered Brierfield’s ability to quickly send correspondence and express packages.

On at least one occasion, Gorgas struggled to simply maintain control of his operation. A dispute erupted between Gorgas and the property’s previous owner, C.C. Huckabee, when Huckabee attempted to reclaim the property during the spring of 1866. Huckabee had sold the property to the Confederate government during the war, before it was seized by the federal government and sold to Gorgas and the Canebrake Company. Huckabee still claimed partial ownership of the land and wanted to profit from it by harvesting timber. Exasperated, Gorgas wrote Huckabee, reminding him that “the US authorities agreed on their part to put us in possession…It will be best that you should remove your mill off the lands belonging to us.”[4]

Often, Gorgas was forced to scale back his operations, sometimes resorting to temporary closures in order to save money. In pleading for better rates, he admits that he is “striving to keep the works in at least partial activity,” while to a colleague he proposes “putting our furnace out of blast for a little while until prices of iron ride somewhat higher.”[5] Ultimately Gorgas capitulated, leasing Brierfield to a man named Thomas Alvis, who ran the operation until the Panic of 1873 forced its closure.

These problems, combined with the inevitable difficulty in obtaining quality equipment and labor in the Deep South, made life very hard for men like Gorgas. They reflect the difficulty encountered by industrialists seeking to establish themselves in the land of King Cotton – under a state government that was unwilling to reign in powerful rail barons, amid a population that was skeptical of industrial labor as an acceptable form of work. In Alabama, they tell a story of missed opportunities and squandered potential. For while the state would eventually be regarded as the industrial capital of the Deep South, she had fallen far short of the ‘New South’ dream that had initially spurred investment in iron forges and coal mines.

Works Cited

[1] W. David Lewis, Sloss Furnaces and the Rise of Birmingham District: An Industrial Epic, (Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press) 8.

[2] Letter to W.J. Hardee, November 23, 1866.

[3] Letter to E.G. Barney, Esq of Selma, March 25, 1866.

[4] Letter to CC Huckabee, March 29, 1866.

[5] Letter to Maj. C.G. Wagner, June 18, 1867.