By: Mark Robison, University of Alabama Information Services Librarian

On December 13, 1819, the last day before the U.S. Congress admitted Alabama to the Union, the Alabama territorial legislature passed a bill incorporating the town of Tuscaloosa (Clinton, Tuscaloosa 26). The Falls of Tuscaloosa, as the village was known prior to incorporation, had witnessed settlement by European Americans since at least 1816, when Thomas York moved to the area from Blount County and planted corn. Others followed, and the area grew, resulting in the creation of Tuscaloosa County in 1818. Immediately after the incorporation of Tuscaloosa in 1819, however, its dominance in the county would be challenged by a rival town located just a few blocks to the west.

Newtown was originally known as The Lower Part of the Town of Tuscaloosa. Tuscaloosa sits on a plot of land then known as Section 22, and this new town lay directly to the west on Section 21. Incorporated almost exactly one year after Tuscaloosa, in December 1820, the town’s name was soon changed to The New Town of Tuscaloosa, and eventually simply “Newtown” (Clinton, Scrapbook 33). Newtown’s genesis involves a man, William Ely, who purchased the lands surrounding Tuscaloosa to raise funds for a Connecticut deaf asylum, thereby incidentally inhibiting Tuscaloosa’s growth and incensing the area’s citizens. Ely sold Section 21 to a dozen prudent investors, who founded Newtown and became some of its preeminent citizens.

Matt Clinton’s Scrapbook (1980) is a collection of articles authored by the late Matthew William Clinton, detailing the history of Tuscaloosa. Clinton taught history and other social studies courses at Tuscaloosa High School for 43 years and was a prolific Alabama historian. His Scrapbook is a collection of his articles, which originally appeared in the Tuscaloosa News between 1967 and 1969, that was posthumously published by his wife, Bernice Blackshere Clinton. She wrote the book’s introduction.

The Hoole Special Collections Library houses multiple copies of Matt Clinton’s Scrapbook, two in the Alabama Collection and another in the Reference Collection, which contains an inscription from Mrs. Clinton herself. This history of Newtown is derived primarily from the details in Clinton’s article, “Newtown: Rise and Fall,” located on pages 32 – 34. Other Scrapbook tales include the origins of the name “Tuscaloosa” and details of the 19th-century urban legend of a tunnel that allegedly connected the Robert Jemison mansion to the river (see “The Tunnel Story Persists,” p. 15).

Newtown was a true rival to Tuscaloosa. Clinton writes, “Newtown was surveyed before Tuscaloosa and consequently grew faster than ‘Old Town’” (Scrapbook 33). In 1822 the citizens voted to move the county seat from Tuscaloosa to Newtown, where a courthouse was constructed at the present-day southwestern corner of Martin Luther King, Jr., Blvd. and 6th Street. Newtown was a hub of economic activity in those days, with several businesses lining its Main Street (36th Ave.), including law offices, doctors’ offices, a hotel and a market house located in the center of the street. Nearer the river stood a cigar factory, a sawmill and a warehouse. Newtown even had its own ferry service to Northport. Both Newtown and Tuscaloosa submitted competing bids to build a bridge to Northport, and the state legislature authorized both on the same day in 1821 (Clinton, Tuscaloosa 44).

By the time a bridge was completed in 1835, however, the battle between the towns had been won. Tuscaloosa became the state capital in 1826, and an act of the state legislature greatly extended Tuscaloosa’s boundaries, thereby ending Newtown’s separate existence (Clinton, Tuscaloosa 54). Even today, however, the effects of Newtown’s history are visible. At Martin Luther King, Jr., Blvd., which formed the north-south border between the towns, the east-west streets make a notable jag, becoming more square on the Newtown side. A handful of beautiful historic Newtown homes still stand today, such as the Carson Home on 36th Ave. This abiding influence is in spite of a horrific tornado in 1842, which destroyed many of the original Newtown buildings, including the defunct courthouse (Clinton, Scrapbook 34).

Regarding the endurance of the town’s name, Clinton writes, “The name of Newtown persisted until after the turn of the century, when that section of Tuscaloosa came to be known as West End” (Tuscaloosa 55). Today a sign along Martin Luther King, Jr. Blvd. demarks the area as the “Newtown Historic District.” However, while several neighborhoods in Tuscaloosa are recorded on the National Register of Historic Places, Newtown is not one of them. Although many locals still recognize the neighborhood as “Newtown,” its history is in danger of being forgotten. Matthew Clinton’s scholarship has played a significant role in preserving the town’s memory.

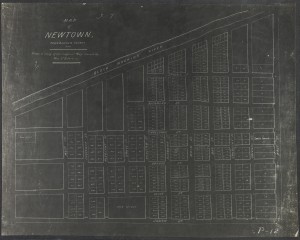

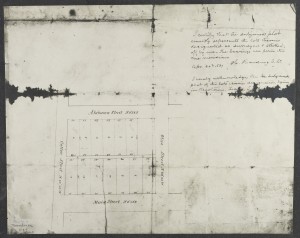

Hoole offers several other clues to the history of Tuscaloosa’s former rival. Copies of another of Clinton’s histories, Tuscaloosa, Alabama: Its Early Days, 1816-1865, can be found in Hoole’s Alabama, Agee and Reference Collections. Its chapter on Newtown has been cited extensively here. Additionally, two maps of Newtown survive in the Hoole Maps Collection, one from approximately 1880 and another from 1887. The c. 1880 map shows Newtown’s original street names and marks the location of the former courthouse.

Works Cited:

Clinton, Matthew William. Matt Clinton’s Scrapbook. Tuscaloosa: Portals Press, 1979.

———. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: Its Early Days, 1816-1865. Tuscaloosa: Zonta Club, 1958.

One Response to Newtown: The Story of Tuscaloosa’s Bygone Rival