By: Christa Vogelius, CLIR Postdoctoral Fellow

Jennie Cheatham Lee, the second choir director at the Tuskegee Institute in Tuskegee, Alabama, served at the Historically Black College during a crucial moment in its history. During her tenure from 1903 to 1928, the Institute transitioned away from the leadership of Booker T. Washington, who had founded the school in 1881 and served as its president until his death in 1915. Tuskegee, like Fisk University where Lee was educated, trained teachers who would serve Southern rural schools and help to shape the musical traditions of the larger African-American community in the early part of the twentieth century.

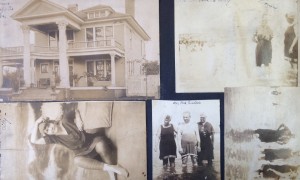

In spite of Lee’s centrality to this mission, not much is known about her life and work. Her personal archive in the A.S. Williams III Americana Collection includes pages from a personal photographic scrapbook that she kept during her years at Tuskegee. The album’s candid images and ephemera capture the day-to-day life of Tuskegee students, teachers, and administrators—including trips to the beach, hat-making classes, and group photos of the choir and singers— but they are supplemented only by a small number of textual documents, most of them printed programs rather than personal manuscripts. The documents include a telegram and letter from Booker T. Washington; a letter from Julius Rosenwald, the businessman and philanthropist who was a prominent supporter of Tuskegee; and letters on the occasion of Lee’s retirement as choir director. Lee’s own writing is sparse.

The place where Lee’s personal voice resonates most clearly, then, is not in textual documents, but in the compilation and arrangement of her photography album. In an essay titled “In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life,” bell hooks writes that “The camera was the central instrument by which blacks could disprove representations of us created by white folks.”[1] Just three years before Lee began her work as Tuskegee, W.E.B. DuBois’s photography exhibit at the Paris Exposition of 1900 had done precisely that, carefully curating portraits of bourgeois respectability to counter popular cultural representations of criminality and poverty.[2] In Lee’s photographic arrangements, we can read some of these same aims. On one page, for instance, a portrait of Lee in a high-collared lace dress is posted next to a postcard image of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, speaking both to her pride in her alma mater, and her ambitions for her work at Tuskegee. The faded inscription on the postcard reads “Band before the crowned heads and Europes’ [sic] smart set.” On the bottom of the page is pasted a photograph of three figures posing around a well-polished car, that ultimate sign of middle-class American attainment.

This album is both deeply evocative and frustratingly silent, speaking to some of the complications of doing historical research with primarily visual evidence. And yet these images also argue powerfully that there is more to institutions like Tuskegee than their printed tracts, treatises, and mission statements. In albums like Lee’s, we can find a counter-balance to the official documents that were dis-proportionally written by male administrators, a space where the presence of female instructors and students is everywhere apparent.

[1] bell hooks, “In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life,” in Picturing Us: African American Identity in Photography, ed. Deborah Willis (New York: New Press, 1994), 42-53, 50.

[2] See Shawn Michelle Smith, “’Looking at One’s Self the Eyes of Others’: W.E.B. Du Bois’s Photographs for the Paris Expositions of 1900,” in Pictures and Progress: Early Photography and the Making of African American Identity, eds Wallace and Smith (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012), 274-298.