By: Isabela Morales, PhD candidate at Princeton University

This post continues a conversation Cool@Hoole began on Monday with Isabela Morales, who did her undergraduate work at the University of Alabama and whose research in the Division of Special Collections in the S.D. Cabaniss papers, now available digitally through Acumen, led to her current position as a PhD candidate at Princeton.

What was your project?

The seminar paper focused on a family of enslaved women and children in Huntsville, Alabama: the Townsends. In the 1820s, a white Virginian named Samuel Townsend had moved with his brothers to Alabama, which had only recently become a state and was fast becoming the destination for ambitious men looking to make their fortunes planting cotton. Samuel and his brothers did just that—but they did it, as did the vast majority of white migrants, by exploiting the labor of slaves. And again like many Southern slave-owners, Samuel sexually exploited the enslaved women on his plantations. Before his death in 1856, Samuel had fathered nine children with seven enslaved women, many of whom already had children by their enslaved husbands. The stories of these women, like countless other African and African American women, would probably be lost to history if Samuel hadn’t done a peculiar thing before his death: he wrote a will that promised them and their children emancipation, as well as almost the entirety of his $200,000 estate.

Samuel had no wife and no white children—meaning his only children were the ones he held as slaves on his plantation. Strangely, despite his abhorrent treatment of their mothers, with his will Samuel essentially intended to turn people who were legally property into his legal heirs. Not surprisingly, his plans met with resistance from his white relatives. As a result, the court proceedings that dragged on for four years after Samuel’s death etched the Townsend women and their children into the historical record. The sources are scarce, and even those that do exist (Samuel’s will, his attorney’s inventories, probate court records, and depositions) were created by white men with great power over the enslaved Townsends. My challenge was to reconstruct the Townsends’ lives and experiences to the best of my ability—without their voices. Professor Shaw’s guidance throughout this process was indispensable. Her own work grapples with the complicated nature of sources, the challenge of reading between the lines to find enslaved women in the archive, and the uses of imagination in writing about the past; her advice and example still influences my research today.

How did you locate the collections that suited your project?

I had never done archival research before taking Professor Shaw’s seminar on American slavery, so the task seemed especially daunting (I’d thought figuring out how to work the microfilm readers in Gorgas Library had been difficult). When it came time to choose my research topic, I was nearly in a panic. The Hoole Library has a wealth of materials on slavery in the American South, but if anything that made the decision harder—I was drowning in options. Finally (the night before my initial proposal was due, actually) I decided just to sit down at my computer and, if necessary, read through all of Hoole’s finding aids until I found something that sparked my interest. I got lucky. At the top of the third page of search results, I found the listing for the S.D. Cabaniss Papers: the legal files of a Huntsville attorney, including records from the estate of Samuel Townsend, a white cotton planter who named his nine enslaved children his heirs. I hadn’t known such a thing was possible in the antebellum South, and the story of these women and children gripped me instantly.

Researchers sometimes talk about moments of serendipity, and this was definitely one. I know I can’t count on lightning striking the same place twice, but the experience taught me two very important things I’ll try to pass on to any students starting research projects. First, please, please, please manage your time better than I did; it’ll save a lot of pain and anxiety down the road, I promise. And second, don’t be afraid to follow your gut every once in a while. I’m the kind of person who likes to have a plan, but with archival research you rarely always know what you’re going to find up front. I went to Hoole with a call number and a two-sentence description of the collection I wanted to look at, and it led me to my dissertation. Being an historian is a bit like being a detective: if you find something interesting, even if you don’t know where exactly if will lead, follow it. It might take you to a dead end (don’t worry, everybody hits those), but part of the excitement of research is when that small clue leads you to a big story. That’s what happened with me and the Townsends.

Was there any one particular document that shaped the direction your research followed?

When I began work on my senior honors thesis, I decided to shift from the first generation of Townsend women to Samuel’s children, and I began looking at the dozens of letters written by this second generation to their attorney S.D. Cabaniss. My thesis focused on Samuel’s youngest child, Susanna. Susanna was a young girl navigating between two worlds, and her story fascinated me—she was a cotton planter’s daughter who could claim some of the privileges of European ancestry (emancipation before the Civil War, the inheritance left by her father, the possibility of “passing” across the color line), but also an enslaved woman’s daughter, subject to the authority of the family’s white attorney (who disbursed the estate’s funds), the abuse of her older half-brother Wesley (who acted as her guardian after her mother and only full brother died), and the limitations that a racialized society put on her opportunities for education and employment.

I was able to tell Susanna’s story in part because, between her emancipation in 1860 and her early death in 1869 at age sixteen, she wrote nine extant letters to S.D. Cabaniss. Analyzing these letters taught me a great deal about interpreting sources—I wanted to understand how Susanna saw the world, how her experiences shaped her sense of self, but I had to take into consideration the power dynamics involved in even the simple act of writing a letter. Sometimes, in order to gain Cabaniss’s sympathy and aid, Susanna played on the attorney’s sense of himself as a Southern gentleman, a man bound not only by duty but by honor to protect Samuel Townsend’s children. But at other times, she emphasized her ability to support herself as an adult and spoke knowledgeably about financial matters—after all, she had helped support herself along with Wesley’s wife and children when Wesley was drafted during the Civil War.

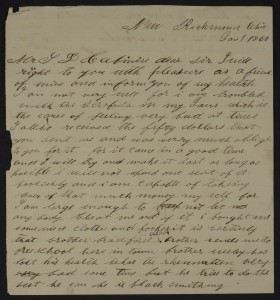

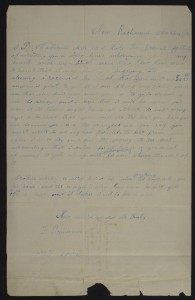

Susanna understood her audience and shaped her missives accordingly, and as I worked on my thesis I learned how important it was to read every letter as an act of self-representation in order to be rigorous in my analysis. But even so, there were moments when I could almost see her in certain lines, where she came to life as a person rather than just a name on an old letter. I remember two letters in particular that struck me as suggestive of her character. In January and April of 1866, Susanna wrote to thank Cabaniss for sending her small disbursements out of the estate. “i will not spend one sent of it foolishly and i am capable of taking cair of that much money my self for i am large enough to not let any body cheat me out of it,” she wrote in January. And then in April: “i will try and put the money to the best advantage that i could for it takes a good deal of money to get along in this country … i know the need of it.” Reading these lines, you get glimpses of how fast she’d had to grow up. Susanna was shrewd and determined, weary and maybe even a little cynical when she wrote those letters. She was thirteen years old.