By Isabela Morales, PhD candidate at Princeton University

This post continues a conversation Cool@Hoole began on Monday with Isabela Morales, who did her undergraduate work at the University of Alabama and whose research in the Division of Special Collections led to her current position as a PhD candidate at Princeton.

On Monday, she discussed why she came to the University of Alabama and chose to study History and American Studies. On Wednesday, she shared her eureka moment in the archives. Today, she will highlight how special collections influenced how she perceives historical research and how her time at Hoole led her to develop her current project.

Did you have any surprising experiences during your time working in special collections?

I was surprised by how emotionally connected I began to feel toward the family I was studying, the Townsends. I know it’s a dangerous thing for an historian to imagine they’ve really come to “know” their subjects, but I think that developing that sense of empathy can be valuable in research as well. Feeling that I was starting to understand, even to such a slight extent, the personalities, goals, and motivations of individuals—Susanna’s pursuit of independence and autonomy, Wesley’s anger and bitterness, their half-brother Thomas’s preoccupation with wealth and respectability—helped me see the Townsends and ultimately write about them as fully three-dimensional people. As an historian I’m interested in what their experiences tell us about post-emancipation America on a macro scale, but they were real people, and coming to care about them as real people keeps my research and writing grounded. I have a strong commitment to narrative and to microhistory, and it’s important to me to remember that the Townsends weren’t metaphors or vectors for historical argument—they were people who actually lived, whose lives mattered, and whose stories deserve to be told.

How has your project developed now that you’ve begun to pursue a PhD at Princeton?

My dissertation is a social history of race, family, and region centered on the Townsend family. After their emancipation in 1860, the Townsends migrated across the American West—some settling in Ohio, a large number in Kansas, and several to Colorado’s silver mines. One of the men, Thomas, went full circle; after a decade in the West, he moved back to Huntsville and purchased the very land where Samuel Townsend had once held him, his mother, and his family as slaves. By bringing all of Samuel’s children—along with the extended Townsend family—into the story, I hope to to compare the nature of race relations both between the West and the South and across the West. What did it mean, for example, to be a mixed-race man or woman in post-Civil War Leavenworth, Kansas? In Reconstruction-era Huntsville? In 1880s Denver? And how did Samuel’s children’s experiences differ from those of their half-siblings and cousins from their mothers’ enslaved husbands? As at UA, I continue to be interested in ordinary individuals’ everyday struggles for survival in changing social and political environments. By following the Townsends, I hope that my project will provide insight into the ways that class, color, and region affected African Americans’ opportunities for economic and social mobility in the second half of the 19th century.

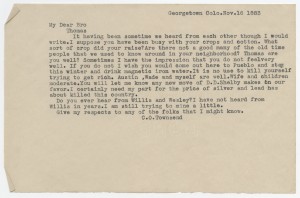

I am especially excited that I’ll have a chance to explore the Townsends’ relationships with each other—and return to the ideas about identity and self-presentation that continue to interest me. The Hoole library has a number of letters written by Colorado silver miner Osborne to his half-brother Thomas, the ambitious attorney and cotton planter in Alabama. As with any source, these letters have to be analyzed critically, but they provide a different perspective than the majority of the Townsend letters. Osborne jokes and chides (“It is no use to kill yourself trying to get rich,” he tells Thomas), argues about politics (by the 1896 Osborne is enough of a Westerner to vote for the famous populist William Jennings Bryant), and reminisces about their childhood—none of which you would see in the Townsends’ more impersonal letters to Cabaniss. Because I am so interested in storytelling, parsing these sources for insight into how the Townsends saw themselves as individuals and as part of a family network is just as important to me as connecting them to larger arguments about American society at large.

Because my focus remains on the Townsends, the Cabaniss papers at Hoole still form the heart of my dissertation. But in order to gather more information about the communities that the Townsends inhabited—to go both broader and deeper—this summer I took my first dissertation research trip to state and local historical societies in Kansas. The materials I found at the Carroll Mansion Museum and the Richard Allen Cultural Center in Leavenworth, Kansas (newspapers, city directories, death certificates, just to name a few) were exceptionally valuable—not to mention how generous the archivists were with their time. (One woman gave me a ride back to the motel so I didn’t have to walk in the 100 degree heat!) And in the digitized photography collections of the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, I finally found a photograph of one of the Townsends. At long last being able to put a face to a name—even just one—sounds like a such a little thing, but I was thrilled and moved and inspired all over again. It reminded me of nothing so much as that first trip to Hoole in 2009, when, hardly knowing even what I was looking for, I fell in love with research.

Thank you for your time, Isabela. It’s been a pleasure to speak with you. Best of luck in the future!