By: Rachel K. Deale, History PhD student

Throughout the nineteenth century music played a vital role in American life. Music could be heard everywhere from parlor pianos, to soldiers marching on the battlefield, to church congregations, and to slaves laboring in the fields. Although music played an important role in in the antebellum south, the war escalated the cultural significance music had on southern society. Music was no longer just a form of entertainment. Music became a social outlet for southern soldiers and civilians to express their innermost thoughts, feelings, and concerns during the conflict.

Throughout the nineteenth century music played a vital role in American life. Music could be heard everywhere from parlor pianos, to soldiers marching on the battlefield, to church congregations, and to slaves laboring in the fields. Although music played an important role in in the antebellum south, the war escalated the cultural significance music had on southern society. Music was no longer just a form of entertainment. Music became a social outlet for southern soldiers and civilians to express their innermost thoughts, feelings, and concerns during the conflict.

Once the southern states decided to secede from the Union in 1860 and 1861, they could no longer depend upon Northern presses to produce sheet music. As a result, southerners established their own publishing houses throughout the Confederacy. In 1860, brothers and former music teachers Armand Edward and Henry Blackmar established what would become the most prolific and successful music publishing company in New Orleans, Louisiana. Upon the Union capture of New Orleans in April 1862, Henry moved their business to Augusta, Georgia. John C. Schreiner began another prominent publishing house in 1860 called John C. Schreiner & Son in Macon, Georgia. In 1863, George Dunn quickly rose in notability when he joined the music publishing business by opening George Dunn & Company in Richmond, Virginia.

The W.S. Hoole Special Collections Library collection of Confederate sheet music published by Blackmar and Company, John C. Schreiner & Son, and George Dunn & Company illustrates four themes: sentimental, instrumental, religious, and nationalistic songs. Southerners used sheet music to help encourage a sense of Confederate nationalism throughout the war. Songs such as “Hurrah for Our Flag” celebrated the Confederate flag as their “standard of hope and of trust.” As Confederates struggled to produce a national anthem they decided to write new words to be sung to the tune of the French “Marseillaise” because the song elicited strong emotion, loyalty, and was not originally produced in the north. This initiative led to the publication of A.E. Blackmar’s popular “The Southern Marseillaise.” But as the war continued, Confederates grew dissatisfied with sharing their national anthem with France and were even more discouraged upon learning of the song’s northern popularity. In addition to promoting Confederate nationalism, sheet music also fostered a sense of state pride. Songs such as “The Alabama” eulogized the brave service of the south’s most successful commerce raider the CSS Alabama.

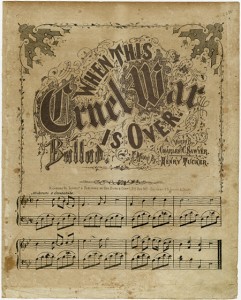

Although many soldiers enjoyed mother songs like “Rock Me to Sleep, Mother,” “Call Me Not Back from the Echoless Shore,” and “Mother is the Battle Over,” mother songs were really written for women on the home front. The songs romanticized soldiers by suggesting that their love for family and country took priority over their thoughts, conditions, and feelings on the eve of battle. This sentiment was encouraging to those at home because it presented their sons as strong and selfless individuals. “When This Cruel War is Over” became a popular song both at home and on the battlefield because it encouraged an end to the war and the soldiers’ return home. Instrumental songs were also well liked on the home front. Publishers increased sales of instrumental and dance music by naming the music after famous confederate generals even if the composition shared little to no relation to the general whose name was on the cover. Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard appeared on more music than any other Civil War officer having numerous Quicksteps and Grand Marches named in his honor.

Music also was a morale booster and patriotic outlet for Confederate soldiers. “The Volunteer” or “It is My Country’s Call” became a popular song among soldiers that also helped encourage many to enlist early in the war. The songs sung in camp or while marching often referred to Confederate victories such as Manassas, Chancellorsville, and Chickamauga. While most soldiers learned songs by word of mouth, they also frequently requested their family to send them songbooks to enjoy on the battlefield. Receiving music from home provided soldiers with another way to connect with their families.

Want to learn more about the exhibition? Read our “Curating the Confederacy” five-part series, read the curatorial essay for Making Confederates, and/or come to our Curator’s talk today, April 21, 2015, at 3:30 PM in the A.S. Williams III reading room, level three, Amelia Gayle Gorgas Library.