The College of Arts & Sciences is today kicking off a year-long event, the Year of Utopia. We wanted to get in on the action and showcase some volumes in Special Collections that help trace the literary history of the concept.

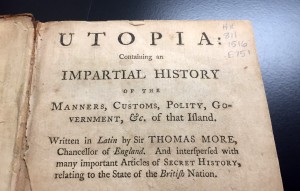

Let’s start with the work that coined the term, Thomas More’s Utopia (1516), translated from Latin into English in 1551. Utopia translates to “no place” (source), but it also carries a connotation of sound-alike eutopia, or, “good place.”

This volume is from exactly 200 years later. Much had changed in the country’s government and society — notably, the English Civil War had happened, the Commonwealth experiment come and gone — but the yearning for a better society was a constant.

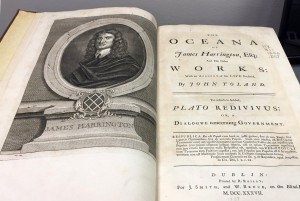

In the wake of the Civil War, another meditation on the perfect society was published, James Harrington’s The Commonwealth of Oceana (1656).

This volume is from 1737.

Though similar works to these were published over the course of the 18th and 19th centuries, the 1880s-1890s saw a boom in utopias and counter-utopias, perhaps reflecting the major upheavals in western society that came with industrialization.

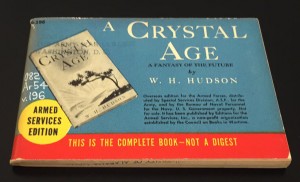

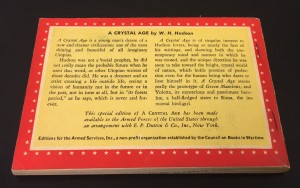

In A Crystal Age (1887), by W. H. Hudson, a narrator falls and hits his head, awakening to a new world of vegetarians who have mostly suppressed their human bodily urges.

This volume is a 1944 Armed Services edition, intended to be read by a serviceman or -woman.

I’d imagine WWII was the perfect time to dream of a utopia.

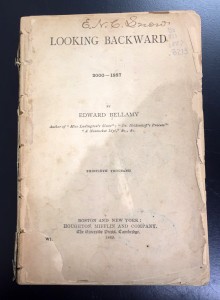

Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward (1888) started a long literary conversation on the concept of the perfect socialist society.

In his novel, the protagonist falls asleep in the late 19th c. Boston and awakens 113 years later to find himself in a heavily industrial society.

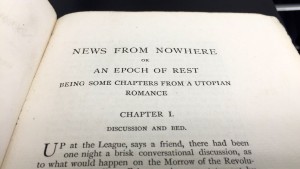

The next year, William Morris, a socialist himself, published News from Nowhere, depicting a different sort of utopia, one more based on nature than machines.

We usually refer to this model as a Pastoral Utopia.

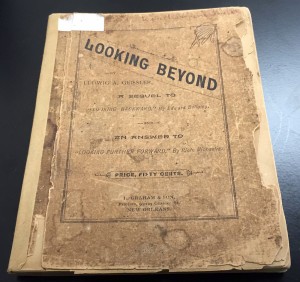

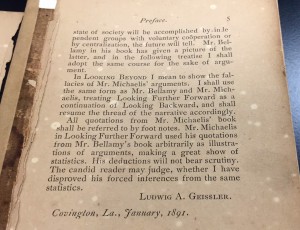

Morris’s response was just one of many. Another was Looking Further Forward, by R. C. Michaelis, which sees Bellamy’s utopia end in violent revolution. In 1891, in response Michaelis’s work, Ludwig Geissler published Looking Beyond.

This work took up where Bellamy left off by retconning the plot of Michaelis’s sequel, treating it as a bad dream or hallucination of the original protagonist.

For a full account of the responses and counter-responses, see this article on Wikipedia.

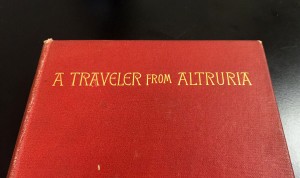

In 1894, William Dean Howells returned the genre to its satirical roots in A Traveler from Altruria. Like More, Howells derives his fictional society’s name from a particular term, altruism, which means “unselfish regard for or devotion to the welfare of others” (source).

In this novel, modern Americans interact with Mr. Homos, from the utopian society of Altruria, and find their society wanting. The work was a comment on Gilded Age capitalism.

Utopian fiction has a long history. The University Libraries hold many of these works, as well as secondary sources that discuss them. In Scout, search by the subject utopias to find both.

2 Responses to The Year of Utopia