African Americans occupied a wider variety of spaces in the social order of 19th century America than you may realize. Because of the horrors of slavery, there are an uncountable number who, at least individually, are all but erased from the historical record but whose collective presence is felt most strongly. But there are other black lives that sometimes did make a more public mark but have until recently been less comprehensively examined: those of the free and the freed, especially before and during the Civil War and during Reconstruction.

Today, we focus specifically on just seven examples of men of color living in the 19th century, to see how and to what extent their diverse social positions and individual stories are revealed in our collections. Unfortunately, there are sometimes more questions than answers.

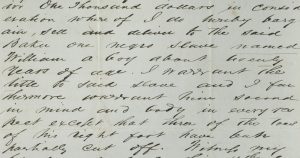

William, laborer, enslaved

Encountered in the collection Jacob Ramser Receipt (MSS.1695)

This collection consists of a receipt by Ramser acknowledging the payment by Alpheus Baker of $1,000 for a male slave named William, aged about 20, whom Ramser warrants to be of sound mind and body, “except that three of the toes of his right foot have been partially cut off.” The transaction was witnessed by J. M. Buford and E. S. B. Fort.

This collection consists of a receipt by Ramser acknowledging the payment by Alpheus Baker of $1,000 for a male slave named William, aged about 20, whom Ramser warrants to be of sound mind and body, “except that three of the toes of his right foot have been partially cut off.” The transaction was witnessed by J. M. Buford and E. S. B. Fort.

William must have been a strong young man and a good laborer to have commanded such a high price. One wonders how and when his toes were mutilated, if Ramser’s use of the passive voice (“have been partially cut off”) is because he did not know or because he wanted to distance himself from his own actions.

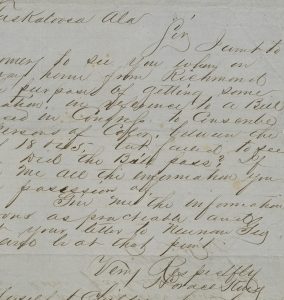

Horace King, architect and builder, enslaved then freed

Materials found in the collection Robert Jemison Jr. papers (MSS.0753)

Horace King was technically a slave, and while that technicality matters, it also doesn’t quite capture the reality of his life. King learned to build bridges from his owner, John Godwin, and eventually the two formed something of a partnership such that he was able to travel on his own to take on projects across the South. He was apparently the stronger engineer and craftsman; his master handled the business side of things. He was freed in the 1840s, and he continued to ply his trade and also had a part in the Reconstruction government of the state. (Read more about him in the Encyclopedia of Alabama or the New Georgia Encyclopedia.)

Horace King was technically a slave, and while that technicality matters, it also doesn’t quite capture the reality of his life. King learned to build bridges from his owner, John Godwin, and eventually the two formed something of a partnership such that he was able to travel on his own to take on projects across the South. He was apparently the stronger engineer and craftsman; his master handled the business side of things. He was freed in the 1840s, and he continued to ply his trade and also had a part in the Reconstruction government of the state. (Read more about him in the Encyclopedia of Alabama or the New Georgia Encyclopedia.)

A note on his connection to the Jemison papers: As a major player in pre-war Tuscaloosa, Robert Jemison was in a position to undertake serious improvements to the town’s infrastructure, including commissioning a bridge to be built over the Black Warrior River. Although in the end King was not chosen for the job, Jemison was keen to keep ties with him for future projects, including the construction of a bridge in Columbus, Mississippi, which is why the two were in correspondence over the course of several years.

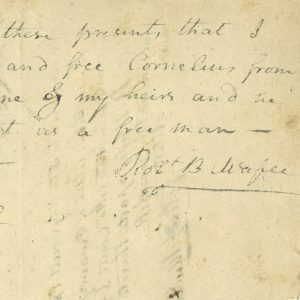

Cornelius, enslaved then freed

Encountered in the collection Robert B. McAfee Letter of Emancipation (MSS.1698)

This collection consists of a letter by McAfee dated March 2, 1813, freeing a slave named Cornelius “from all claims from me & my heirs and he is hence forth to be & act as a free man.” The letter was witnessed by James Campbell; on the obverse annotation states that it was recorded at the May sitting of the Mercer County Court, attested by John Jethen. (The state is uncertain; there is a Mercer County is Illinois, New Jersey, and Ohio.)

This collection consists of a letter by McAfee dated March 2, 1813, freeing a slave named Cornelius “from all claims from me & my heirs and he is hence forth to be & act as a free man.” The letter was witnessed by James Campbell; on the obverse annotation states that it was recorded at the May sitting of the Mercer County Court, attested by John Jethen. (The state is uncertain; there is a Mercer County is Illinois, New Jersey, and Ohio.)

One wonders what exactly Cornelius did for McAfee and why McAfee wanted to free him. Was Cornelius the exception, or was it McAfee’s habit to do this? More importantly, did Cornelius know this was coming (was he working toward it?) or was it a surprise? And how did he feel?

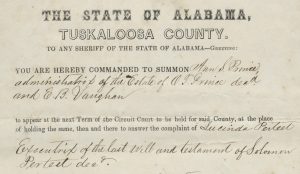

Solomon Perteet, builder and businessman, free

Reflected in the collection Solomon and Lucinda Perteet papers (MSS.1129). (The image below is from the Jemison papers, MSS.0753.)

Perteet was born free in Georgia, the son of a white woman from a modest slaveowning family and presumably one of her slaves. He moved to Tuscaloosa in the early 1800s, where he gained prominence in the community as a craftsman and property owner. He purchased his wife, Lucinda, and her child in order to free them, and he apparently did the same for several other enslaved African Americans. (Read more about him at the Tuscaloosa Area Virtual Museum.)

The collection includes receipts and legal papers, mostly pertaining to Lucinda as she handled his estate and lived on after him.

John Smith, sailor, presumed to be free

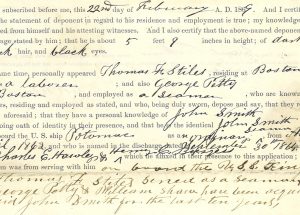

Encountered in the collection Five certificates attesting to the service of African American sailors during the Civil War (MSS.4149)

The affidavits in this collection confirm the service of African American sailors during the Civil War. In them, white citizens of Massachusetts in good standing, swore under oath that the black person named in the document served aboard the U.S. ship listed in the capacity stated. John Smith was on the U.S.S. Potomac from August 1861 to April 1862, and his comrades from the U.S.S. Kingfisher attested to that fact.

The affidavits in this collection confirm the service of African American sailors during the Civil War. In them, white citizens of Massachusetts in good standing, swore under oath that the black person named in the document served aboard the U.S. ship listed in the capacity stated. John Smith was on the U.S.S. Potomac from August 1861 to April 1862, and his comrades from the U.S.S. Kingfisher attested to that fact.

Smith’s name is so generic as to suggest it might be a pseudonym or a dodge to avoid giving his legal name. If this is true, one wonders why he would do that — to hide from something or to restart his life afresh, or perhaps both? We don’t know where he was born, so we don’t know if he was always free or simply freed or emancipated by the time he served. What’s striking is that the system still required white people to vouch for him. These men did, however, which shows their recognition of his role in the war effort alongside them.

Chauncey Leonard, chaplain, free

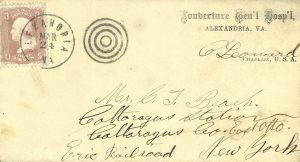

In the collection Chauncey Leonard letter (MSS.4148)

Chauncey Leonard was one of only fourteen African American chaplains in the U. S. Army during the Civil War. He served in the L’Ouverture Hospital in Alexandria, Virginia. The L’Ouverture Hospital opened in February 1864 to serve as the hospital for African American troops and contraband civilians (i.e., escaped and freed slaves). It was set up outside the divisional structure of the other military hospitals in Alexandria. Chauncey Leonard opened a school for the soldiers at L’Ouverture that was well attended.

Chauncey Leonard was one of only fourteen African American chaplains in the U. S. Army during the Civil War. He served in the L’Ouverture Hospital in Alexandria, Virginia. The L’Ouverture Hospital opened in February 1864 to serve as the hospital for African American troops and contraband civilians (i.e., escaped and freed slaves). It was set up outside the divisional structure of the other military hospitals in Alexandria. Chauncey Leonard opened a school for the soldiers at L’Ouverture that was well attended.

The collection contains a letter from Leonard to C. T. Beach, stating that Mr. Beach’s letter to his son Peter had been received and read. Leonard also thanked Mr. Beach for the money used to pay an assistant teacher in the hospital’s school.

Jeremiah Haralson, politician, enslaved but emancipated

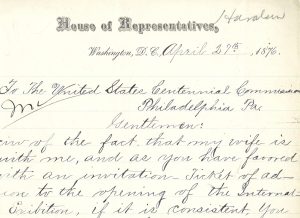

In the collection Jere Haralson letter (MSS.0625)

Jeremiah Haralson, born on a plantation in 1846 near Columbus, Georgia, was raised as a slave. After emancipation, he taught himself to read and write. He moved to Alabama, where he served as the first black member of the State House of Representatives in 1870. He served in the state senate in 1872 and in the U.S. Congress from the 44th district from 1875 to 1877. At other points in his life, he was a farmer, a coal miner, and perhaps a minister. (Read more about him in the Encyclopedia of Alabama, or about his career at the U.S. House of Representatives archive.)

Jeremiah Haralson, born on a plantation in 1846 near Columbus, Georgia, was raised as a slave. After emancipation, he taught himself to read and write. He moved to Alabama, where he served as the first black member of the State House of Representatives in 1870. He served in the state senate in 1872 and in the U.S. Congress from the 44th district from 1875 to 1877. At other points in his life, he was a farmer, a coal miner, and perhaps a minister. (Read more about him in the Encyclopedia of Alabama, or about his career at the U.S. House of Representatives archive.)

The collection contains a letter written in 1876 by Rep. Haralson to the United States Centennial Commission in Philadelphia, requesting an additional invitation for his wife to attend the opening of the Centennial International Exhibition of Industry.