By: Donnelly Walton, Archival Access Coordinator

Archival Access Coordinator Donnelly Walton as a child

I grew up in Mobile, Alabama, a town known as the “Mother of the Mystics.” Although Mobile’s Mardi Gras is perhaps not as famous as the celebration in New Orleans, Mobile boasts the oldest Mardi Gras in the country. I grew up feeling pride in my town, and I loved the Carnival season, which ends on Mardi Gras Day (Fat Tuesday). Each year I woke on Ash Wednesday with a certain sadness that it was over.

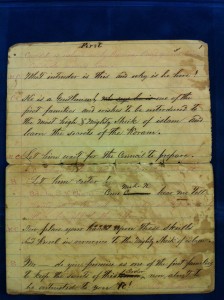

Began in 1703, Mobile’s Mardi Gras is celebrated for about three weeks. Parades for the general public start around each night at 6:00. But for those involved in the secret societies, Mardi Gras activities last all year with meetings, parties, and other events. In Mobile, these secret societies are called “mystic societies.” In New Orleans, they are known as krewes. Since the 1830s, members of the societies remain anonymous. Not all societies actually parade; those that don are referred to as “parade krewes.” When parading, the men wear elaborate costumes with masks and a hat to protect their identity. The A. S. Williams III Americana Collection at The University of Alabama holds an extremely rare 1847 notebook from the Cowbellion de Rakin Society, the first such society in Mobile that held parades. The notebook includes the induction ceremony script.

The Mystic Stripers always ride on the last Thursday night before Mardi Gras Day. Stripers are an old krewe–the oldest still parading–with a unique history as they began as a working man’s mystic society, rather than one for the Mobile elite. The Stripers parade, held on a Thursday night, always signaled the beginning of the climatic final parades. Until that night, the parades are much shorter. On Friday, the “Crewe” (Crewe of Columbus) rides; on Saturday, it is the Mystics of Time’s turn.

The Mystics of Time, with their trademark dragon floats that weave in and out of the streets of downtown Mobile spitting fire, will always be my favorite. The dragons were and still are delightfully frightening to me. However, I also have fond memories of the Stripers. While no one is supposed to know the identity of a krewe member, it is often hard to maintain secrecy if you do know who they are. A man named Joe worked with my dad and he was a Striper. I have stood in downtown Mobile screaming “Hey Joe!” in hopes of getting bombarded with cheap trinkets, candy, and necklaces. I felt thrilled when “Stripers Joe” recognized my family in the crowd and flooded us with throws, what we call the items that krewe members throw to the crowd.

My family wasn’t involved in a krewe; we simply enjoyed it. Other families, who were also not involved in mystic societies, choose to ignore Mardi Gras and simply enjoy the vacation that so many people in Mobile get for Mardi Gras. Public schools close on Monday and Tuesday; some private schools close the whole week!

For me, Mardi Gras season would mean rushing home from school to finish homework. Then we’d get ready for the parade. “Getting ready” involved dressing warmly (even mild nights in this coastal city felt quite chilly with the wind from the water) and getting a bag for your throws. The bags, just like the throws, have evolved over the years. In the 1970s and 1980s, we took paper grocery sacks that would often be filled with necklaces, doubloons, candy, and the all-important, much sought after Moon Pie. Now, it seems that you’re lucky to have enough to fill your pockets, much less the bags made of recycled materials or the festively decorated Mardi Gras bags I own. We’d park downtown on Water Street and then, as a special treat, walk a few blocks to Royal Street, where we’d eat dinner at the Royal Dog House. I still remember the taste of that chili cheese dog, always drunk with a cold Coke. We’d return to our car on Water Street and wait for the parade. In those days, the parade routes were different. We were able to stand in front of our car and enjoy the parade as it passed in front of us.

2014 Mystics of Time float, courtesy of Allyson Holliday

How can I explain the excitement of waiting for a Mardi Gras parade? There was a sequence of events that even the youngest of children knew and waited for eagerly. Long before the parade reached your area, there were no rules. Cars and trucks still passed by until the traffic slowed to a trickle. Then the street vendors appeared, pushing their grocery carts decorated and filled with their goods: silly hats, flags, and other items typical of events for children, along with my favorites, cotton candy and snap ‘n’ pops (outlawed long ago). Next came the police—in cars and on motorcycles and horses—who closed the streets. Even the police got in the spirit. Often, they did tricks on their motorcycles. Our parents would allow us to sneak peeks down the street to see if we could see the actual floats coming in the distance. I still remember the excitement of seeing emergency vehicles, followed by a marching band, with a beautiful float behind it. The parades could last anywhere from twenty minutes to well over an hour, depending on how many floats and bands there were (and how many floats broke down during the parade!).

As the Mardi Gras season progressed, parades became progressively longer and more fun. I remember feeling so disappointed when I went to other parades (Christmas, Fourth of July, UA Homecoming Parades) in non-Mardi Gras towns. Where were the fun bands that stopped and danced in front of you? Where were the drunk men falling off floats as they pummeled you with candy, doubloons, necklaces, and Moon Pies? For all of that is Mardi Gras. I loved sitting on my father’s shoulders, holding my bag, and being overwhelmed with excitement when a costumed man in a full mask leaned over to toss me cheap goodies. While there are all-women parade krewes, the traditional male parade krewes are historically more rowdy.

The Sunday before Mardi Gras Day is known as Joe Cain Day. Joe Cain was a nineteenth-century Mobilian credited with bringing Mardi Gras back to Mobile after the Civil War in 1867. He infamously dressed as a Chickasaw Indian chief, Slacabamarinico, and paraded through the streets. Although some children attend Sunday’s festivities in Mobile, my parents, like most of my friends’ parents, never allowed us to go on this day, which might be the one day during Mobile’s Carnival season that most resembles New Orleans’s less family-friendly version of the season.

The Saturday before Joe Cain Day, however, hosts the most tame and gentle of festivities: the Floral Parade. The Floral Parade features the Mobile Carnival Association’s juvenile king, queen, and court. These are the children of Mobile’s elite society, who will often grow up to be members of King Felix III and his queen’s court. (All Mardi Gras kings have been known as Felix III since the early 1900s. Sewlyn Turner IV is this year’s King Felix III. View more photos of him on Alabama.com.)

I was awestruck by the queen, her beautiful ladies-in-waiting, King Felix III, and his knights when I was a young child. I still look forward to the Mardi Gras insert in the paper that shows all the court. I love to see and read about the queen’s dress and the history behind it. This year’s queen, Madeline Maury Dowling, asked the Mardi Gras gown designer Homer McClure to create a gown around the eighteenth-century necklace she received as a gift from her parents. Her dress and jewelry follows a historical precedent: since the late 1800s, the king and his queen have worn elaborate costumes. The Hoole Library has a several publications about the history of Mobile Mardi Gras, including some written by former queens, documenting the history of the court and their beautiful, extravagant clothing.

When I was a teenager, my mother and I watched a special on TV about Mardi Gras. A granddame of old Mobile society described the Mardi Gras of her youth, mentioning all the “many lovely parties” [insert the most beautiful and drawn out pronunciation of “parties” that one can imagine]. I realize now that the lady was most likely Emily Staples Hearin, author of several titles on Mardi Gras in Mobile now held by the Division of Special Collections. Ms. Hearin’s father was head of the Mobile Carnival Association (MCA) for over forty years.

As the years progressed and parades no longer traveled down Water Street, my family moved our viewing spot to Royal Street, which was much more convenient to the Royal Dog House. A lot of things have changed over the years. Through the 1980s and 1990s, we stood in front of the dilapidated remains of the old Battle House Hotel, established in 1851. Thankfully, now it has been beautifully restored. Snap ‘n’ pops were outlawed years ago. Small pieces of candy are virtually nonexistent today; popular plastic cups replaced them. There are now many varieties of moon pies, but actually catching an original Moon Pie is quite a feat. The Royal Dog House closed at some point. I think that “Stripers Joe” passed away or is too old to ride. The downtown Krispy Kreme, our post-parade treat, closed a few years ago.

But what hasn’t changed, and what will probably never change, is that families in Mobile enjoy the festivities for a few weeks each year, and more and more people travel to Mobile annually to take part in the city’s party.

Here are a selection of materials relating to Mardi Gras in Mobile in the Division of Special Collections.

Manuscripts

Cowbellion de Rakin Society initiation ceremony script

For more information on the Battle House Hotel, see the Alabama hotels and resorts of the past collection

Publications

Dean, Wayne. Mardi Gras : Mobile’s illogical whoop-de-doo, 1704-1970. Mobile’s carnival, the Gulf city’s great Mardi Gras festival; origin, growth, progress, and attractions for today. What it has done for Mobile in the past and present. Chicago : [s.n.], c1971. Hoole Library Alabama Collection. Call Number: GT4211.M6 D4 1971

Hearin, Emily Staples and Kathryn Taylor DeCelle. Queens of Mobile Mardi Gras, 1893-1986. Mobile : Museum of the City of Mobile, 1986. Hoole Library Alabama Collection. Call Number: GT4211.M6 H47 1986

Louisville & Nashville Railroad. Mardi Gras carnivals : New Orleans, Mobile and Pensacola, 1912. Publication:[s.l. : s.n., 1912?]. Hoole Library Rare Books Collection. Call Number: F379.N53 L6 1912x