By: Nancy Dupree, Ph.D, Curator of the A.S. Williams III Americana Collection

Editor’s Note: The James McClung Sieg journal currently is on display in the reading room of the W.S. Hoole Library. Visit these reading room display cases for a rotating gallery of our most recent acquisitions!

With the recent acquisition of a portion of the daily journal of James McClung Sieg, the Special Collections Library has added a significant piece to its collection of materials on the life of William Henry Sheppard, one of the most remarkable men of his time—a man who “stood before kings, both white kings and black kings.” Sheppard has strong local connections: though he was a Virginian by birth, he was trained for the Presbyterian ministry at the Tuscaloosa Theological Institute, forerunner of Stillman College; his name is memorialized in the Sheppard Library at Stillman and in the name of the central Alabama Presbytery of Sheppards and Lapsley. His wife, Lucy Gantt Sheppard, was a native of Tuscaloosa.

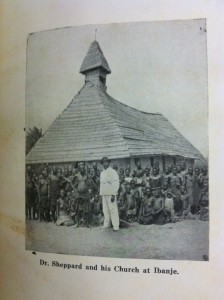

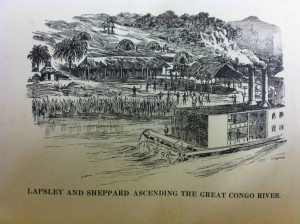

Special Collections owns two copies of Sheppard’s memoir, Pioneers in Congo, (published by the Pentecostal Publishing Company in 1900) in which he recounts his early years in Africa, where he spent the better part of twenty years. He went out to the Congo in 1890, with Alabama Presbyterian minister Samuel Lapsley, and they established a mission compound near the Congo River. Both conducted religious services and schools, but otherwise they divided the work; Lapsley handled the accounts and dealt with the colonial officials; Sheppard learned the local dialects, hunted and fished for food, and developed a strong rapport with the people of the surrounding villages. Both were frequently ill with tropical ailments; Sheppard was strong enough to throw off his twenty-two attacks of malaria, but Lapsley died after only two years. Sheppard, joined by several other missionaries (including Sieg), was able to continue the work, and for the next seventeen years he was the leader among the missionaries and a towering presence among their African neighbors, who called him “Shoppit Monine,” “the Great Sheppard.”

Sheppard’s memoir is primarily an account of his travels among the villages, by river and on foot through the bush. He was explorer as much as missionary; he learned local languages and gathered as much information as he could before he set out. He was usually met with hospitality and curiosity (hundreds of people would gather to see him and hear him preach), but the Bakuba king had sent out word that outsiders would not be allowed into his country. Sheppard set out to go to this forbidden land, learning as much about it as he could. He described the trip to his men: “I told them, from the information that I had, that the trails which had been made by elephant, buffalo, antelope, and Bakuba natives were many and they led over long, hot, sandy plains, through deep dark forests, across streams without bridges, and through swamps infested with wild animals and poisonous serpents” (91). Sheppard and his men worked their way through the bush into the capital of the land of the Bakuba, where Sheppard was able to convince the king that he was not an enemy but a man to be trusted. He was thereafter well received. In his descriptions of his travels Sheppard describes in detail the lives of the people he meets; he was an explorer in the best sense of the word, studying distances, routes, watercourses, animal patterns and other natural features; for his work he was granted membership in the Royal Geographical Society of Britain. In particular he reveals his appreciation for the artefacts of the area; he is recognized today as one of the first American collectors of African art. Pioneers in Congo is illustrated with photographs made by Sheppard himself; he was known for his photography.

Sheppard was deeply concerned about the colonial treatment of the Africans; they were cruelly terrorized into producing large amounts of rubber for European trade, causing them to neglect their farms and live in poverty. Toward the end of the nineteenth century Sheppard and other missionaries spoke out strongly against these abuses; Sheppard made several trips through the bush to investigate conditions and used his Kodak camera to make pictures of the ravages of people and villages. In 1907 he published an article in a missionary journal accusing the trading companies of mistreating the Africans. He was charged with libel and threatened with prison, but the charges were dropped after a dramatic trial. Sheppard became an international celebrity; he was received at the White House by President Theodore Roosevelt. In 1910 the Sheppards retired from the African work and he served as a pastor in Louisville, Kentucky until his death.

Sieg’s diary covers the years 1907-08 and part of 1910. By this time the mission was well-established; several missionaries lived in the compound (made up of several buildings) and traveled around the countryside to visit various churches and schools. The manuscript gives a striking picture of a community isolated in a foreign culture, made up of a small group of like-minded people working for a common cause. Maintaining a semblance of their own lifestyle lifestyle seems to have required constant effort; Sieg reports that he is called on for handyman projects like building and painting. On trips through the bush he goes hunting for food; he reports killing his first hippo, “shooting it between the eyes with the Winchester.” Most impressive is the fact that this was a racially integrated community made up of white Southerners like Sieg (a Virginian) and black Southerners like the Sheppards. There is a strong sense of the unity of the group in Sieg’s narrative; this is significant because the group is racially integrated. He makes no difference between blacks and whites; he refers to all his fellow missionaries formally, as “Mr.”, “Mrs.” and “Miss,” although for a Southern white to refer thus to African-Americans was practically unknown at the time. The missionaries live on equal terms; they socialize frequently, help each other with projects, cooperate in the work. At this point Sheppard is clearly the group’s leader. Sieg describes Mr. and Mrs. Sheppard as “extremely hospitable”; they often entertain the whole group for a meal (including Christmas dinner), followed by phonograph music. Mrs. Sheppard and the other women are partners in the work, though usually described as involved with children and women.

Although most of Sheppard’s own papers are held by the Presbyterian Historical Society in Philadelphia, the University of Alabama Special Collections has a collection of materials that will support research on this important figure in American and African history and culture of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.