By: Allyson Holliday, W.S. Hoole Library Complex Copy-Cataloguer

This post is the second of a two-part series in recognition of Holocaust remembrance week April 27–May 4, 2014. (Better a little late than never!) Part I of this series featured testimony from Joe Sacco and James Chancy. The theme designated by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum for the 2014 observance is Confronting the Holocaust: American Responses.

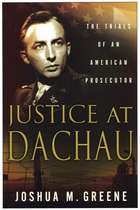

William (Bill) Dowdell Denson (1913-1998) was born in Birmingham, Alabama in 1913. His grandfather was a judge on the Alabama Supreme Court and his father also practiced law. After graduating from West Point, Bill went on to Harvard Law School and joined his father’s firm in Birmingham. By the age of twenty-eight, he had argued over 300 civil cases.

In 1941, Bill returned to West Point to teach law to the cadets. By January 1945, the United States began to prepare for war crimes trials against Nazi Germany. Bill’s reputation for diligence in the courtroom was awarded by an invitation to join the Judge Advocate Generals, the Army’s legal division. In July 1945, after working on smaller cases around Germany, Bill received a commission to serve as the chief prosecutor in “The Dachau Trials,” which would bring administrators of Nazi concentration camps at Dachau, Mauthausen, Buchenwald, and Flossenburg to justice.

This thirty-two year old soft-spoken lawyer from Alabama endured an incredible shift from teaching law at West Point to assembling a team and leading the prosecution of war crimes that courts had never seen before. His prosecutorial team had no background in war crimes and had to weigh the charges for the atrocious crimes against humanity that were committed by Nazi Germany at these concentration camps. A makeshift courtroom was set up at Dachau – symbolically important because it was Hitler’s first concentration camp. Bill had seen the suffering and destruction caused by the war in Europe. However, it was not until he began to interview witnesses that the full depth of the horrors became apparent.

Overshadowed by the more prestigious Nuremberg trials taking place, Bill’s courtroom at Dachau became the scene of nearly three years of legal proceedings against the men and women who ran the four concentration camps in his jurisdiction. The defendants on trial at Nuremberg had given orders…but never wielded guns. However, the defendants at Dachau were personally responsible for the torture, starvation, and execution of hundreds of thousands of men, women, and children.

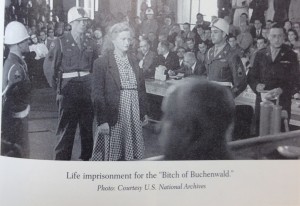

Denson would prosecute a total of 177 Nazi Germans. Among those on trial were Dr. Klaus Schilling, the man responsible for hundreds of deaths due to his medical experiments into a cure for malaria; Edwin Katzen-Ellenbogen, a Harvard psychologist turned Nazi informant; and Ilse Koch, better known as the “Bitch of Buchenwald,” whose macabre collection of items such as photo albums made of tattooed skins, a prisoner’s shrunken head, and human bone lamps horrified the world.

Ilse Koch was the wife of Buchenwald commandant, Karl Koch. She was known to have singled out prisoners for beatings and torture. She was pregnant when brought to trial and therefore escaped the death penalty – receiving a life sentence instead.

Clemency hearings were later granted and Koch’s sentence was commuted to four years. Bill Denson began an aggressive campaign against these actions that led to a Senate subcommittee investigation. This investigation enraged Bill, who had endured physical and emotional exhaustion, a divorce, and even a palsy-like trembling in his hands during the years of trials. He had successfully prosecuted more war criminals than any lawyer in history. He did not want to see these crimes go unpunished. The commutations that had already occurred were not overturned but any new clemency rulings were halted. Ilse Koch was eventually tried by a German court and drew another life sentence to be served in Germany. She committed suicide in 1967.

As Senate Group Probed Reduction of Ilse Koch’s Sentence, Stars and Stripes photo from December 13, 1948

Years passed, and the horrors of World War II began to fade. In 1948, Bill returned to the United States, as chief of litigation for the Atomic Energy Commission and represented the commission at the spying trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Bill married Constance von Francken-Sierstorpff, the daughter of a family he had met in Germany, in 1950. He became a partner in a New York law firm and had three children. He never talked of his experiences at Dachau and kept them to himself.

Decades passed, but the turmoil and genocide in Bosnia, Cambodia, and Rwanda made Bill question his silence. He had to make sure the legal precedents established at Dachau were recognized. He and his prosecutorial team had succeeded in establishing personal responsibility for crimes committed in war. Future and current despots needed to know that if they scorned the rule of law, they would be punished. To accomplish this and spread the story of the Dachau Trials, Bill travelled to Washington, D.C., searching in the National Archives, looking at microfilm of trial transcripts, photographs, newspaper articles, and his own hand-written summations to build a personal archive. Through publications and speaking engagements, Bill returned the atrocities at Dachau to national conscience.

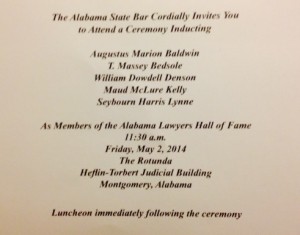

Invitation inducting William Dowdell Denson to the Alabama Lawyers Hall of Fame which was sent to John and Mary Bess Paluzzi. Mary Bess Paluzzi is the Associate Dean of the Division of Special Collections here at UA.

Upon his death in 1998, Eli Rosenbaum, of the United States Department of Justice, had this to say, “Bill Denson’s death deprived the world of one of this century’s great champions of human rights and human dignity. His truly remarkable career inspires awe to this day, particularly among those of us who carry on the work he began” (Greene, n.pag.).

This month, William D. Denson was posthumously inducted into the Alabama Lawyer’s Hall of Fame. The legal precedents set at the Dachau Trials have aided with war crimes trials in The Hague, Bosnia, and other international courts. Thanks in part to his work, crimes against humanity are recognized and punished as part of international law.