By: Nancy DuPree, Curator of the Williams Collection

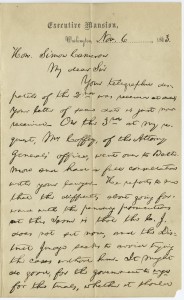

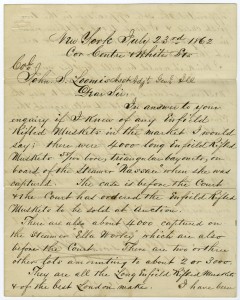

Despite the excitement over the Lincoln letters covered in Monday’s post, the documents themselves appear rather ordinary. The paper has yellowed over the years, although the writing is still strong and clear. Like his literary style, Lincoln’s handwriting is clear and businesslike, but rather plain — unlike John Hancock or George Washington’s fine aristocratic hand. We might not expect to see letterhead stationery from the 1860s, but one letter is written on paper with the letterhead “Executive Mansion,” with a printed line “Washington, ____, 186___.” The blanks are filled in Lincoln’s hand, “Nov. 6” and “1863.”

The two documents, one written by Lincoln to Simon Cameron and one written by Orison Blunt, are not directly related and came into the Collection separately. The Blunt letter is a single item; the Cameron letter is one of a set of nine letters sent to Cameron by various individuals.

The Blunt document dated July 23, 1862, concerns a straightforward item of business: the writer, firearms dealer Orison Blunt, has written to Col. John S. Loomis, assistant adjutant general, to suggest that some British-made Enfield rifled muskets, seized from captured Confederate blockade runners, be turned over to Union units from Illinois, who badly need weapons. Blunt was an expert on weapons, one of the Union’s biggest suppliers of rifles and the inventor of a forerunner of the modern machine gun, as well as a New York City alderman and political foe of Tammany Hall Boss Tweed. On the back of the letter Lincoln wrote an endorsement of the plan, subject to the approval of the Secretary of War.

The Cameron Letter came into the Williams Collection as part of a set of letters addressed to Simon Cameron, a native of Pennsylvania who had a successful career in business. Beginning as a printer’s apprentice, Cameron went on to found and run a bank and two railroads as well as serve in politics. He is credited with the creation of a political machine so powerful that he was called “Czar of Pennsylvania”: he served four terms in the U. S. Senate at different times and narrowly lost a fifth race for the U.S.Senate and a race for governor. Cameron harbored ambitions to be President; after an abortive campaign for the 1860 nomination he was appointed Secretary of War by President Lincoln, but his tenure was stormy and he resigned after a year. . Despite some differences, Lincoln and Cameron supported each other in several difficult situations, and even after Cameron left the Cabinet the two continued to have a working relationship. Cameron toyed with the idea of supporting General Benjamin Butler for the Republican nomination in 1864 — and one of the letters to Cameron in the Williams Collection is from Butler, verifying plans for a visit to Cameron — but in the end Cameron campaigned for Lincoln.

Accusations of corruption seem to have followed Cameron all his life; he once defended himself by saying that he did not need to steal because he had a talent for earning money and could get it without stealing. Some of his enemies called him “The Great Winnebago chief” because he had been involved in some rather discreditable dealings with the Winnebago Tribe. Cameron is credited with the definition of an honest politician as “one who, when bought, will stay bought.”

Lincoln’s letter to Cameron deals with a legal case in Baltimore, where Cameron was being sued by several local officials. During Cameron’s tenure as Secretary of War, he had ordered the arrest of the Mayor of Baltimore and several prominent citizens on treason charges. By November 1863 the men had been released, and Cameron was no longer Secretary, but they were suing him for false imprisonment. Cameron had contacted the President urging him to put the men on trial for treason. Lincoln replied to Cameron on November 6—the letter now owned by the Williams Collection. Lincoln’s letter is somewhat noncommittal; he refers to some complications with court schedules, and says that he has sent a lawyer from the Attorney General’s office to talk with Cameron’s lawyer. Lincoln suggests that Cameron talk with his lawyer, presumably about the lawyers’ discussion, and then get back in touch. Lincoln shows himself a shrewd politician: “It might do good, for the government to argue for the trials, whether it should succeed in bringing them on or not.” He does not commit himself to the treason charge plan, however. As it turned out, the cases never went to trial; Cameron may have been disappointed enough with Lincoln that he considered opposing him in the 1964 election.