By: Martha Bace, Processing Archivist

This week, we are featuring a series of blog posts dedicated to our current exhibition up in the Pearce Foyer of Gorgas Library. The exhibition, “Glimpses of the Great War, Abroad and At Home,” was curated by Martha Bace and Patrick Adcock and will be on view until mid-September.

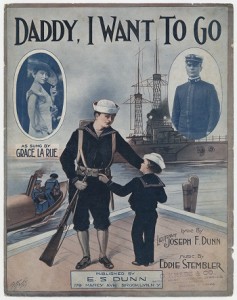

Daddy, I want to go, Words by Lt. Joseph F. Dunn and Music by Eddie Stembler, Wade Hall Sheet Music Collection M1646.S835 D23 1915x

It was the “Great War” – the war to end all wars.

On June 28, 1914, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife were assassinated in Sarajevo, Bosnia, sparking the kindling that ignited the ready-laid bonfire that was Europe. By the end of August, Austria-Hungary had declared war on Serbia, Russia, and Belgium; Germany had declared war on France and Belgium; France had declared war on Austria-Hungary and was invaded by Germany; neutral Belgium was also invaded by Germany; and Great Britain had declared war on Germany and Austria-Hungary. It wasn’t until April 6, 1917, that the United States finally entered the conflict following the sinking of the RMS Lusitania and seven US merchant ships by German submarines.

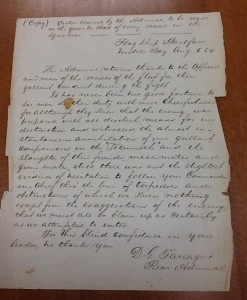

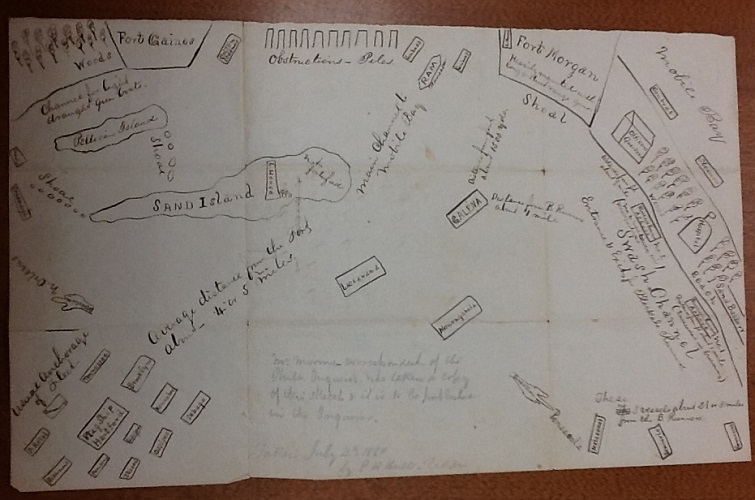

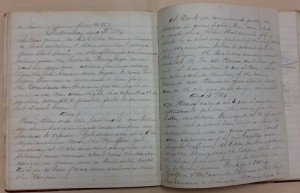

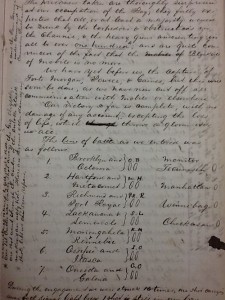

Commemorating the 100th anniversary of the beginning of World War I, the University Libraries Division of Special Collections mounted an exhibit in the Pearce Foyer of Gorgas Library featuring selections from their collections that offer a glimpse into the lives of the men who fought in the conflict and their families and friends left behind. The exhibit showcases material from several collections including: the Walter Bryan Jones papers; the Hughes family papers; the Schaudies, Ragland, and Banks families papers; the Wade Hall World War I photograph collection; and many others.

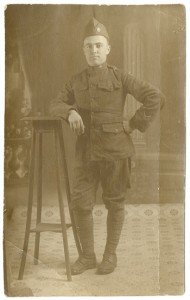

One of the more fascinating parts of the exhibit is the uniforms and military paraphernalia from the Walter Bryan Jones papers and the Hughes family papers. The tunics especially command attention in that they are much smaller compared to the size of many 20-something young men today [Jones and Eli Hughes (whose tunics are shown) were 22 and 25 years old, respectively]. Besides the uniforms – which are interesting enough – the military equipment that is displayed shows only a small portion of what a soldier was expected to carry on his back. Indeed, in a letter home to his mother, Arley Hughes (Eli’s older brother) says, “Mamma, we had a 12 mile hike from our last English camp to port. Eli and I made [it] in good shape while some larger lads failed. Honestly I believe I can carry 100 lbs. 12 miles in 6 hours.”

The majority of the photographs on display are from two separate collections. The larger framed portraits are from the Schaudies, Banks, and Ragland families papers, while the smaller, “black and white” photos are from the Wade Hall World War I photograph collection. Very few of the individuals in the photos from these two collections are identified in any way, which leaves you to wonder if they came home to their families or not.