By: Amy Chen, CLIR Postdoctoral Fellow

In honor of Bastille Day, this week Cool@Hoole will provide readers with a three-part overview of the Division of Special Collection’s French holdings. Today, early modern books will be covered; on Wednesday, the French Enlightenment will be explored; and, on Friday, our series will wrap up with a discussion of French Revolutionary pamphlets.

Early modern France, or the age of the Ancien Régime, was an absolute monarchy during the period between the Renaissance and the Revolution (1453-1789). Society was structured into three estates: the first, clergy; the second, aristocracy; the third, the remaining population. Early modern France was geographically much smaller than it is today, with the northern border areas serving as autonomous regions. Additionally, it had a smaller population due to the confluence of the Black Plague (1346-1353) and the Hundred Years War (1337-1453), which lowered population levels significantly for, prior to these events, France was the third largest nation in the world after China and India.

The most famous monarch of this period was Louis XIV, the “Sun King,” who ruled for seventy-two years. He advocated for the divine right of kings; centralized the state; built the Palace of Versailles; legalized slavery, but mandated that slaves be kept within intact families; supported the arts, including the authors Molière and Racine; and served as the most powerful monarch in Europe. All of his immediate heirs died before him, so it was his great grandson, Louis XV, who would succeed him.

The Division of Special Collections at the University of Alabama holds over two hundred items from the era of the Ancien Régime. If you would like to search for these books, go to Scout and limit your search by the date range and location on the left-hand column. The date range should be 1453 to 1798 and the location should specify books from Hoole Special Collections Library. Early histories, political works, and accounts of colonialism can all be found — although it helps if you can read French!

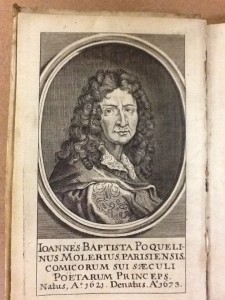

If you are interested in literature, Jean-Baptiste Poquelin (1622-1673) was the most famous writer of this period. He was known for his comedy and, as he felt plays were meant to be acted, he rarely published. For this reason, inconsistent records of his ninety-five works are found today. Dom Juan (a French Don Quixote) and The School for Wives are two of his significant plays. The title page from his Histrio Gallius, Comico-Satyricus (1695) can be seen below the cut.