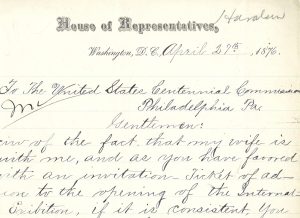

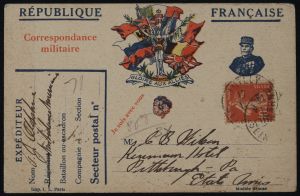

From the Valentine J. Oldshue papers, circa 1917

World War I was fought between multiple countries in two main alliance groups, making the process of ending the war complicated. In some ways, it began with Allied power Russia’s separate peace with the Central Powers, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, signed in March of 1918. On September 29, the Allied Powers signed the Armistice of Salonica, ending the war with Bulgaria. A month and a day later, an agreement was reached with the Ottoman Empire, the Armistice of Mudros.

Here we offer transcriptions of letters describing the atmosphere at the front at the time of the final two armistices. Red Cross Lieutenant Hugo Friedman discusses the Armistice of Villa Giusti, the cessation of hostilities with Austria-Hungary, which came on November 4. It was prelude to the cease-fire with Germany exactly a week later, the Armistice of Compiègne, discussed by Porter Rudolph, an Army Sergeant.

Famously, that final armistice came at “the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month.” In the years since then, November 11 has become a day to commemorate not just World War I but service in all wars. In France and Belgium, it is generally still called Armistice Day, while in the U.S. it is known as Veteran’s Day. In Britain and Commonwealth countries, Remembrance Day is fixed to a day of the week, typically a Sunday or Monday near November 11, rather than that specific date.

Lt. Hugo Friedman

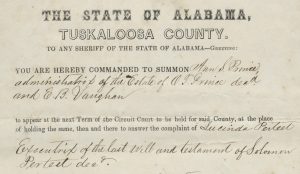

Victor Hugo Friedman (1878-1965) of Alabama served with the American Red Cross in Italy — at various locations as needed, including a canteen high in the Alps at Santa Caterina, risking his life to serve the 2nd Alpini Regiment on Gran Zebrù (or Königspitze) mountain. He was 40 at the time of armistice; he had been in Italy since August of that year and would remain there for approximately six months.

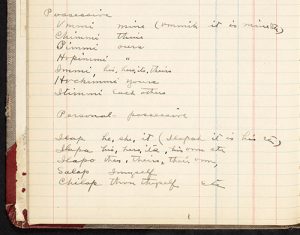

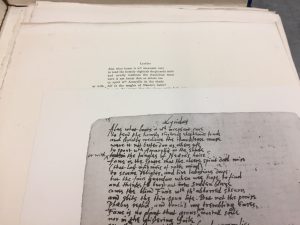

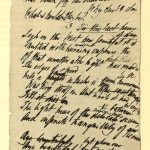

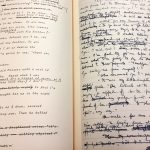

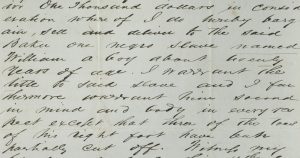

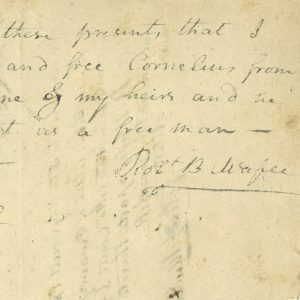

In a letter to his family of November 4, 1918, he describes the mood in a local Italian village after the armistice with Austria-Hungary, their hardships over the course of the war, and the state of Austrian prisoners held locally. It seems to be a carbon copy, which may account for why there is no salutation or signature, except to the added handwritten portion.

Especially pertinent parts of the letter are in bold. Click on any of the thumbnails to see a larger version.

I am especially thankful tonight that I am in Italy, and in that portion of the War Zone that lies nearest to the frontier. For what; just a year ago seemed possible defeat, probable ruination for a fine country and a great people, tonight has culminated in a Grand Victory.

When the armistice with Austria was signed at 3 o,clock today, Austria had been defeated and Italy was a Victor, pure and simple.

I am billeted in a little Village, along with the Colonel and his staff, of perhaps 300 inhabitants and 500 soldiers. On one side of the village tower the Alps. The mountains begin to rise within 300 yards of the little cluster of stone houses and rises, seemingly straight up, above the snow line, 4200 feet above the village. It is on the Eastern side and so precipitous that the sun,s rays do not penetrate this little valley until after 9 o,clock, each morning.

The top of this mountain is the frontier of Italy and Austria and it has been the location of several Austrian outposts, with there batteries of little mountain guns. Many a time during the past ten days 26 shells were fired into it. As has every Italian village, no matter how small, there is a church and a nice brick and stone church at that, with its two large bells placed one above the other.

Now good people, how would you have liked to live in a village, where for three long years of war, terrorized day after day, night after night by the enemy, where the God=fearing people could not even listen to the cheerful sound of their church bells, for those bells had been silent these three years, fearful lest there sound might bring down on the village, iron messengers from the enemy. It was my good fortune, when the clock struck the hour of 3 today, proclaiming the cessation of hostilities, to be standing in this village street. At the first sounds of the bells there was silence for a minute or two. They could scarcely realize their deliverance. Then the soldiers began to cheer and the old men and the women and children ran into the street and burst into shouts. Many cried out of sheer joy, and all of them began to gather around the church as if they wanted to drink in the voices or those bells.

That was 5 hours ago and still those bells are ringing, one after another, they take their turns at the ropes.

Those were the happy ones. But as the corporal (my interpreter) and I were going to my room; about 4 o,clock, we saw the [pg. 2] other side of the picture. Standing in a doorway, crying as though her heart would break, was a girl of about 10 years of age and clinging to her skirts were two little tots, crying also out of sympathy because they were surely too young to comprehend. My interpreter questioned the girl and found that her father had been killed just three months ago, and the sound of these bells had brought back memories. Sitting on a doorstep, we saw a young woman in black, crying. Her husband had been killed recently. And so it was in all of these mountain villages, that are overshadowed by the guns of the enemy. There was joy and there was sorrow.

As I write the soldiers are shooting fireworks and from the Italian outposts upon the tip top of the mountain, the sentinels are sending up many colored signal rockets. Some of them have the little parachute attachments so that the fire will float for a while. They are so very high that they seem to be visiting amongst the stars.

Now the terms of the armistice, as agreed upon about 10 o,clock last night, were these. That the armistice would take effect at 3 oclock today, that whatever line the soldiers were on at that time, they were to hold and that whatever soldiers of the enemy were behind that line at 3 o,clock were to be prisoners of War. So you can perhaps realize what an effort was made to extend the lines into the enemy,s territory as far as possible during the few remaining hours.

And, dear people, such a country for “extension”. Up one mountain, 4000 to 8000 feet then down the other side and then up and down again, continually and snow and ice everywhere. Every officer and every soldier available grabbed their guns and marched to the work and presumably the enemy was making just as strong preparations to stem the tide.

Yet so determined were these Alpini, so brave and so bent on pushing the enemy back off the territory that had been stolen from them in days gone by, that some of the patrols forced their way, 15 and 20 miles back into the enemy,s lines. To one who knows these peaks as I do it seemed an impossibility.

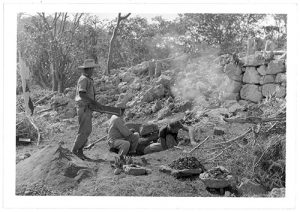

All prisoners, taken hereabouts, must be brought to this headquarters. Here they are questioned and all documents that they may have, are inspected. The first batch that arrived, late this afternoon, consisted of 7 men and a corporal. If you had seen them, you would have wondered how in Heavens name, they could have existed up in the snow, as long as they have. Their cloths hung in rags. Several had only parts of a uniform. Few had overcoats, their hair was long and ragged and they were anything but clean. You seldom see a beggar in America as ragged as they. When I gave them some cigarettes and cigars, they had many smiles for “Americana”. They had never seen an American uniform before and had no knowledge of any Americans in Italy. I made their guards line them up for a photograph and they looked as pleased as children.

Now 4 of these 8 men, were under 20 years of age, 3 were 21 and the corporal was 30. And the pity of it was, that when the examining Officer inspected their pocket=books, full of Post cards and pictures of their home folks and friends, some of the photos were of these same boys, some on football teams, some in family groups, all nicely dressed and at pretty homes. There were absolutely unrecognizable in their present condition. One of them autographed a piece of paper money that he had and gave it me. Another gave me a little military medal. Since then several batches have come in and now (at 11;p;m;) we have just had a phone message stating that others are on the way here.

Now the Austrians, the comrades of these prisoners, perhaps these very same men themselves, are the ones who have terrorized this War Zone for three years. They have perpetrated [pg. 3] every misdeed, they have treated with greatest cruelty all Italian prisoners they have mistreated the women and the old and youthful inhabitants of all Italian villages which they have taken, and yet, today, I have seen these Italian officers and soldiers, with that sympathy which no other Nation possess in like quantity, give to these prisoners comforts and eats and not one harsh word have I heard hurled at them. It is past understanding, when you have heard, as I have, what the Italian people of this War Zone have undergone during the past three years, from this enemy.

Could any one on earth, have aught but tender feelings for such a people.

My comrade and I have had many strenous times in these mountains since my last letter to you. We have carried over comfort and supplies for the American Red Cross to peaks, known the world over, to all mountain climbers, where the snow and ice is perpetual. One of these little outposts is nearly 13000 feet high and is the very highest trench of the Allied Army in the whole War Zone of Europe and one of the highest peaks in the Alps.

We have seen and crossed magnificient glaciers and we have gazed on snow clad mountain peaks, glistening in the sun, one after the other, as far as the eye could reach. From some of the sentinel;s posts we could see many miles into Austria and Switzerland. We have had the enemy, a sentinels, “pot” at us with rifle and machine gun and, tied to a rope alongside Alpini guides, we have scaled icy clefts where misstep meant a tragedy; yet when we would gain our objectives and see the look of appreciation upon the soldier,s faces for the comforts and supplies which we had brought them, we have always felt more than repaid and in our hearts was always that feeling of “doing so little” for these men who were “doing so much” for the Allies and humanity.

A few days ago, I had that honor of being recommended for the “Croce de Guerra”, the Italian Cross of War, I feel that this more than compensates me for all of the strenuous hours I have spent. It seems now that it will only be a matter of a few weeks or months before we all shall be coming home again, flushed with Victory.

With best wishes to all of you, I am,

Dear Folks

Enclose copy of letter here just written to an officer. Some of it is news to you. The Gruppa I am with just rec’d orders be ready move front so I may be in another Country in a day or so.

Looks like the finish real quick now. Think I am getting all your letters and certainly look forward to them. Don’t get over 1 copy out of 10 of Tusc[aloosa] Papers. Certainly sorry hear of Lester [S—?] death. I expect take 2 to 3 months get home after Peace. Maybe longer. Love to all. & Merry X’Mas

Hugo

Sam: might show this Mr Verner & F.M. & any other boys happen to see. Have sent Mr A Lerman [?] & HPL a copy in two of letters.

Sgt. Porter Rudolf Jr.

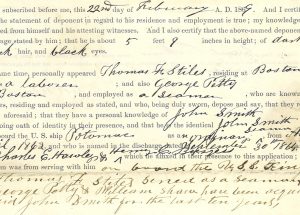

Porter Breckenridge Rudolf Jr. (1893-1948) of Illinois served in the 33rd Infantry Division, a National Guard unit, in the 108th Engineer Regiment. He had just turned 25 at the time of armistice; he had been in France since May of that year and would remain overseas until June 1919.

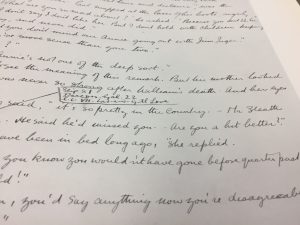

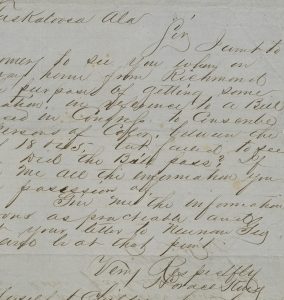

In a letter to his father, Porter Sr., of November 21, 1918, he addresses in detail what it was like at the front on the day of the armistice, presumably in northeastern France, near Verdun. He specifically mentions being a part of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, the last major Allied campaign of the war, which involved over 1 million American soldiers. He also mentions the recent arrival of his “kid” brother, Roy, a 22-year-old Corporal with the 304th Tank Brigade. Edna is their sister.

Especially pertinent parts of the letter are in bold. Click on any of the thumbnails to see a larger version.

France Nov. 21 1918

My Dear Dad.

This is quite a novel experience for me that is writing a letter to you personally. Of course all of my letters to mother are intended for you and the family as well as her on account of my having twice to write each on individually.

As you may know, the “stars and stripes”, the weekly paper of the A. E. F. has requested all men of the A. E. F. to write a Christmas letter to Dad and have it in the mail before the 24th of this month. As I consider myself a small cog in this [pg. 2] machine I take it that they mean me just as much as anyone else so here goes Dad and if you get half as much pleasure reading it as I have in writing it I know that the time was well spent.

To begin with Dad since this request was just published that great day which we have all been fighting and waiting for finally arrived when on this misty and foggy morning of Nov. 11 – 1918 at 11 o’clock hostilities ceased. I personally am very proud to say that on that final morning I was in the live and went thro’ an experience I shall never forget although being in other engagements which were a lot “better” for example “The Argonne”

Well, we left camp on the night of the 10th expecting to go over the top in ^the morning. Being in charge of a platoon our work as laid out to me was naturally more or less on my mind as we marched that dark night. We ^were delayed many times on the road by ammunition transports and other outfits going to the live also. We finally arrived at the shell-torn village (which was in the live) at 400 A.M. and according to orders expected to “hop the bags” at 5

At 5 there was no order and when at 6:30 there still [pg. 3] were no orders we were hoping against hope that the Armistice had been signed which would prevent anyone being killed on the final day which to us was “zero” in luck. However our guns were in operation and it seemed as though Fritz never sent over so many big shells and such a lot of gas as he did that night and morning. At 930 the Infantry went over but still we had no orders and we were still in the town dodging those damn shells. Then just a few minutes after 930 the order came [pg. 4] for our guns to cease firing. Buglars were sent out on the field and frantically blew “Recall” for the Infantry to come back. Such a feeling as passed thro’ us I cannot describe with pen and ink. The war was over although Fritz kept ^up a terrific shelling until 11 o’clock sharp when all guns were silenced, for all time I sincerely hope, because Dad while I wouldn’t sell my experience for millions still I had enough as they say over here, “We are fed-up on this war stuff”.

[pg. 5] We walked around that town in a daze after 11 o’clock fearing that we would wake up at any minute and find it all a horrible dream.

By the time darkness fell we had not received our orders to move back to camp so had to go back to our bed, a rock pile in a shattered railway station. However Dad we were a happy little platoon realizing that only accidents can keep us from seeing home and the loved ones again. No shells can now “bump us off” How different this night was from the many preceeding ones. Now we built a blazing big fire when in the morning shells were walling. There were fires all around us which over in Fritz’ live he was sending up all kind of his flares lighting the heavens and, what was no man’s land just a few hours before, in wonderful fashion.

The next morning Fritz was already on his way to the Rhine. Another Sgt. and myself walked over a couple of miles behind his lines [?] and talked and visited with the Jerry’s as though there never had been a war. I [?] believe if such a thing was possible that they were happier than [pg. 6] we were. They couldn’t shake hands with us fast enough. Well Dad I could write volumes tonight but will save some for that happy day when I get home.

Since the 11th I have not had time to write anyone because I have spent only one day in camp. However I did manage to send mother and also Ruth a “whiz-bang” (Field post card) telling you that I was safe and sound.

We have been on road work so the Armies of Occupation could move forwards.

We came back to camp today and according to [pg. 7] persistent rumors we will be one of the 1st Divs home.

I wouldn’t be surprised if I have seen the front for the last time. I think that in the next few days we will move back and start drilling in preparation to leaving for home.

If Roy is now over here he can call himself lucky because it will be nothing but a pleasure trip. He will probably stay in some seaport town until time to board ship again.

[pg. 8]I am very glad the kid had no time to see active service.

Well Dad I think I will bring this letter to a close hoping I haven’t bored you.

Wishing each and every one of you the merriest of all Christmas days I am

Your

Loving Son,

Porter

[signature of censor: John H. Chase, 2nd Lt. Engr.]

P. S. Pass on the Christmas Greetings to all of my friends and relatives. I may not have time to write them personally.

Po.

P. S. I am enclosing a Christmas Card for Ruth. Mother will know what to do with it. I didn’t seal it because I tho’t the base censor might want to look at it.

Po.

Other Armistice Accounts

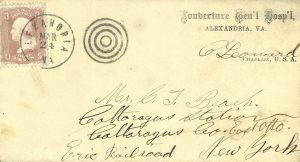

Weir (first name unknown) served in a field hospital in France, as part of the 3rd Infantry Division, a Regular Army unit, in the Sanitary Train. It is a bit unclear who he is writing to. Based on the content of the three letters we have, “Mother” may be (1) his own mother, making little Genie his sister; (2) a wife who is mother to Genie, their child; or (3) an adult sister with a child named Genie, his niece.

- In a letter to his family of November 6, he notes the November 4 armistice with Austria-Hungary and his hopes of a cessation of war with Germany as well, though he doubts it will be very soon. The handwritten addition to the typed message dates from Armistice Day itself. Weir is not a particularly careful typist; typos and missing words are from the original.

- Read Weir’s letter in our digital repository

From the Valentine J. Oldshue papers, circa 1916

Alston Fitts (1867-1950) of Alabama, a doctor, served in the Army Medical Corps, at Camp Hospital 14, in Issoudun, France. He was 51 at the time of armistice; he had been in France since January of that year and would remain overseas until March 1919.

- In a letter to his wife, Marie, of November 13, 1918, he shares mixed feelings, as during the celebrations he has heard about the death of someone back home. He also mentions logistical issues to be worked out in order to get him home when the time comes.

- Read Dr. Fitts’s letter in our digital repository

Andrew Lewis Dawson (1895-1968) of Alabama served in the Army Medical Corps at Base Hospital 40, in Sarisbury Green, England, at a manor house called Sarisbury Court (also known as Holly Hill House). He was 23 at the time of armistice; he had been in England since the previous month and would remain overseas until April 1919.

- In a letter to his mother, Margaret, of November 17, 1918, he discusses life at their hospital, away from the front. The brother he mentions is probably Eugene, who was around a decade younger and still at home. The quotation he gives at the outset is a paraphrase of lines from the poem “The Pessimist” by Benjamin Franklin King, circa 1894.

- Read Cpl. Dawson’s letter in our digital repository

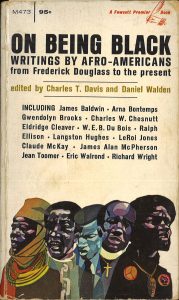

Richard A. Long was an academic and public intellectual who founded the department of African American studies at Atlanta University. He also taught at Emory University. (source:

Richard A. Long was an academic and public intellectual who founded the department of African American studies at Atlanta University. He also taught at Emory University. (source:  While there were undoubtedly more posters made for World War II, due to our longer and deeper involvement in that conflict, posters from the first “Great War” provide just as interesting a glimpse of the politics of the day, not to mention the art styles! According to the Library of Congress, “During World War I, the impact of the poster as a means of communication was greater than at any other time during history. The ability of posters to inspire, inform, and persuade combined with vibrant design trends in many of the participating countries to produce thousands of interesting visual works” (

While there were undoubtedly more posters made for World War II, due to our longer and deeper involvement in that conflict, posters from the first “Great War” provide just as interesting a glimpse of the politics of the day, not to mention the art styles! According to the Library of Congress, “During World War I, the impact of the poster as a means of communication was greater than at any other time during history. The ability of posters to inspire, inform, and persuade combined with vibrant design trends in many of the participating countries to produce thousands of interesting visual works” ( Processing our posters was time-consuming. Most had long sides from 30-40 inches, some up to 60 inches, so they required two people to safely manipulate or move. We had to temporarily colonize a couple of large tables to use as work surfaces and order several custom boxes for archival storage. The posters then had to be arranged into series.

Processing our posters was time-consuming. Most had long sides from 30-40 inches, some up to 60 inches, so they required two people to safely manipulate or move. We had to temporarily colonize a couple of large tables to use as work surfaces and order several custom boxes for archival storage. The posters then had to be arranged into series.