By: Ellie Campbell, JD and University of Alabama MLIS graduate student

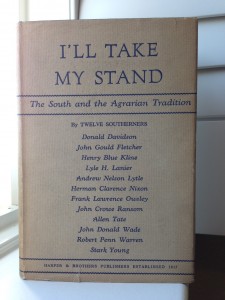

In 1930, a group of self-designated “Twelve Southerners” published I’ll Take My Stand: the South and the Agrarian Tradition, a book of twelve essays defending what they perceived as Southern virtue against the forces of Northern industrialization. The roots of this manifesto began with a series of small, informal gatherings of a handful of Vanderbilt University students, professors, and community members in 1915 in Nashville Tennessee. They met on campus and at various members’ homes to discuss philosophy. Several participated in World War I, and after some of them returned to campus to finish their education, the discussions turned to poetry. Influenced by some of the European modernists like T.S. Eliot, they founded a literary journal, The Fugitive, in 1922. The journal lasted three years, and only produced four volumes, before ending due to financial difficulties and the lack of an editor.

Over the course of the 1920s, some of the veteran Fugitives turned their attentions to Southern culture and history, spurred by the critical writings of Baltimore journalist and editor H.L. Mencken, as well as Chapel Hill sociologist Howard Odum. In particular, Mencken’s scathing coverage of the 1925 Scopes “monkey trial,” in which high school science teacher John T. Scopes was prosecuted for teaching evolution in Dayton, Tennessee, ridiculed the people of the state and the region as “gaping primates,” “yokels of the hills,” and “fundamentalist bigots.” Though Odum’s work was less abrasive than Mencken’s, they shared both a friendship and a highly critical view of the South. Mencken and Odum both contributed to developing a body of scholars and critics to fight what Mencken deemed “the Sahara of the Bozart,” his phrase for the emptiness of the Southern cultural landscape. Mencken influenced a wide variety of writers, both black and white, including James Branch Cabell, Ellen Glasgow, Thomas Wolfe, Langston Hughes, James Weldon Johnson, and Richard Wright. Meanwhile, Odum founded the department of sociology at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, and contributed to the field both through his own scholarship and by recruiting talented professors and students who work also critiqued the South and its culture.

Mencken and Odum’s criticism was keenly felt by John Crowe Ransom, Donald Davidson, and Allen Tate in particular. They recruited the rest of the Twelve Southerners in an effort to defend what they saw as Southern virtue, in reaction to the demon industrialism. However, none of the contributors were farmers by trade or birth, and only one of the essays, Andrew Lytle’s “The Hind Tit,” specifically addressed agriculture. Only one essay, “The Briar Patch,” by Robert Penn Warren, mentioned race as an aspect of Southern life; Warren praised Booker T. Washington’s plan for agricultural and vocational training for African-Americans and called for fairness within the then-current system of segregation. Davidson found the piece to be offensively progressive, but Tate managed to convince him to keep it in the book. Other essays lauded a white culture of privilege built on vague notions of an agricultural system, without any understanding of the reality of that system, including the evils of slavery, tenant farming, sharecropping, or peonage. Practical solutions to the South’s poverty were nowhere to be found.

I’ll Take My Stand was published in 1930, and was widely reviewed in the South. However, the book only sold a little over two thousand copies before going out of print in 1941. It was finally reissued more than twenty years later, after several of the contributors had gained a measure of success. The best known by far was Robert Penn Warren, who went on to win the 1947 Pulitzer Prize for the Novel for All the King’s Men and the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1958 and 1979. Warren, alongside Fugitive and Agrarian admirer Cleanth Brooks, also founded the literary journal, The Southern Review, at Louisiana State University in 1935. Warren and Brooks co-authored several influential poetry and literature textbooks, including Understanding Poetry and Understanding Fiction, which highlighted Southern authors. Several others of the twelve also went on to distinguished careers in academia. Andrew Lytle published several novels, founded the Sewanee Review, and taught English at the University of the South for many years. H.C. Nixon taught history and political science at Vanderbilt, Tulane, and the University of Missouri. Allen Tate and Stark Young became well-known for their novels, poetry, and literary criticism.

Though philosophically muddled and lacking an understanding of the larger economic and social problems confronting the South in the 1920s and 1930s, I’ll Take My Stand remains a key part of Southern intellectual history for its insight into the academic and social criticism debates of its time, and its role in the early lives of some of the South’s major writers and critics.

Editor’s Note: If you would like to do more research on this topic, check the Southern Literature catalog in the Williams Collection.