By: Ellie Campbell, JD and University of Alabama MLIS graduate student

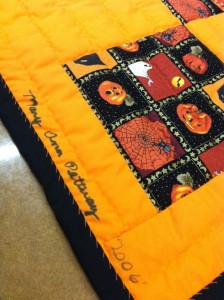

The Wade Hall and Gregg Swem American Quilts Collection contains quilts from the mid-nineteenth century up to the present day that demonstrate the breadth and depth of this American art form. The collection includes the quilt pictured here, a Halloween-themed quilt made by Mary Ann Pettway of Gee’s Bend, Alabama. [Editor’s Note: This quilt’s identifying number is NN-JEES | J5]

The quilters of Gee’s Bend have a unique place not only in Alabama history, but in modern American art as well. Dated November 2, 2006, our quilt shows how the Gee’s Bend legacy lives on in the 21st Century. Though it is not as abstract as some of the more famous examples, Mary Ann Pettway’s Halloween quilt still displays some of the asymmetric qualities that make Gee’s Bend quilts so unique in American textiles.

Gee’s Bend is located in Wilcox County in the Black Belt of Alabama. Enclosed on three sides by the Alabama River, the area was first settled around 1816, when Joseph Gee founded a plantation on the river. Several thousand acres passed from the Gee family to Mark Pettway of North Carolina in 1845. Pettway forced his slaves to march across four states to join the more than 100 slaves that already belonged to the Gee plantation. Many of the citizens of Gee’s Bend retain the Pettway name to this day, including Mary Ann Pettway, who made this quilt.

After the Civil War, many of the former slaves remained in the area and became tenant farmers. The local population suffered yet again when the value of cotton dropped nearly ninety percent in the 1920s, and then became a social experiment in the New Deal during the 1930s. Several of the Farm Security Administration photographers visited Gee’s Bend, including Arthur Rothstein and Marion Post Wolcott. Their photos helped bring government attention to Gee’s Bend. Several federal and state agencies bought property, built houses, and sold homesteads to the former tenant farmers. Owning property allowed several generations of Gee’s Bend residents to remain in the area, long after the local economy ceased to support small farmers. This continuity contributed to the residents developing their unique quilting styles.

The 1960s brought more changes to Gee’s Bend; Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. visited in 1965 and inspired many residents to march with him from Selma to Montgomery in support of voting rights. In retribution, many of the residents were jailed, fired by their white employers, had bank loans unexpectedly called in, or had the few remaining tenant farms bulldozed. The river ferry service – the only way to get from Gee’s Bend to the county seat to vote, minus an unpaved dirt road – was abruptly cancelled, and would not be restored for thirty years.

That decade also brought the birth of the Freedom Quilting Bee, which formed to raise money for the families in the area. Sears hired the Bee to make standard bedcovers and pillow shams for department stores, which provided steady work for seamstresses and plenty of scraps. However, by the early 1980s, the Bee was mostly inoperative, and Gee’s Bend might have passed into history as a footnote except for the efforts of Atlanta art dealer William Arnett.

Arnett began his career collecting Asian and Mediterranean art, and shifted into African art in the 1970s. In the 1980s, he became interested in art by African-Americans in the Deep South, in particular that of Thornton Dial and Lonnie Holley. Arnett was familiar with quilting traditions in other African-American communities in the South, and was stunned by the quilts he discovered in Gee’s Bend in the late 1990s. Arnett began buying quilts in the area. He was already in the process of editing a massive book, Souls Grown Deep: African American Vernacular Art of the South. Arnett helped put together an exhibit of Gee’s Bend quilts, which were shown in museums across the country in 2002-2005. The art world began to take notice after a glowing review in the New York Times called the quilts “eye-poppingly gorgeous” and compared them to Matisse and Klee. Gee’s Bend experienced a quilting renaissance. The cooperative was reformed, and many women in the area work there today.

The renaissance has not been without its controversies; several of the quilters have sued Arnett over profit disputes. Arnett has often been criticized for his interactions with the artists he promotes, most famously by a 1993 episode of “60 Minutes,” which depicted Arnett as exploitative, buying art from poor, uneducated Southern blacks and selling to other rich, white art collectors. The truth, as always, is considerably more complex; Arnett has profited from his tireless promotion of African-American vernacular art, but so have his artists. Without his support, the quilts and quilters of Gee’s Bend would not have experienced the respect and acclaim they do today. Many of the more recent quilts, including our Halloween quilt, might not have been made at all, were it not for this renewed interest in Gee’s Bend and its people. Their quilts hang on the walls of some of America’s most prestigious museums, and are included in collections like ours at Hoole, but many of the families of Gee’s Bend still live in the kind of poverty that characterizes rural, Black Belt Alabama.

Perhaps the best reading of the quilts of Gee’s Bend, and their inclusion in our archive, prompt us to think not only of how far we have come in valuing the history and artistic contribution of these women, but also of how far we have yet to go.

For further reading, see:

Dewan, Shaila. “Handmade Alabama Quilts Find Fame and Controversy.” The New York Times. 29 July 2007.

Kimmelman, Michael. “Jazzy Geometry, Cool Quilters.” The New York Times. 29 November 2002.

Moerringer, J.R. “Crossing Over.” L.A. Times. 22 August 1999.

Wallach, Amei. “Fabric of Their Lives.” Smithsonian Magazine. October 2006.