By: Dr. Stacy Morgan, Associate Professor in American Studies

Our pedagogy series is a way to highlight innovative teaching using primary sources housed in the Division of Special Collections. Interested in reviewing our earlier features? If so, check out Brooke Champagne’s Honors First Year Writing classes from Fall 2013 and Amy Chen and Kate Matheny’s collaboration to bring the theme of “In the Archives” to the majority of Honors First Year Writing classes during Fall 2014.

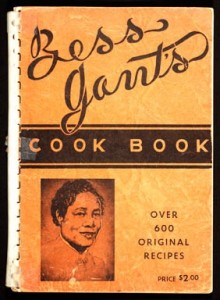

This semester I’m teaching a graduate seminar for the Department of American Studies entitled “American Folklore.” The course is divided into four units that examine various folk traditions pertaining to stories, foodways, music, and art. In addition to in-depth discussion of course content on these topics, we spend time virtually every week considering the advantages and limitations of wide-ranging research methods, such as ethnography, oral history & interviews, and the examination of archival materials. Within this framework, setting up one week in the foodways unit for my students to spend time with material from the David Walker Lupton African American Cookbook Collection at Hoole Special Collection Library was a no-brainer, since it offered students the opportunity to work with diverse archival documents that ranged from the early 20th century to the relatively recent past.

As I suggested to my students by way of introduction to this session, cookbooks offer potential windows onto several different types of historical information. At the most basic level, cookbooks provide information about what kinds of foods and beverages people consumed in particular time periods, as well as insight into how such dishes were prepared, what ingredients were used, and, often, at least some suggestion of why such dishes were popular. Thus, cross-referencing cookbooks from different time periods can be a means of charting change over time with respect to the content, technology, and preferences of U.S. foodways traditions.

Because many of the cookbooks in the Lupton Collection were self-published by individuals or local community institutions, a number of them contain not only recipes, but also statements of specific regional, ethnic, and/or religious identities. In this way, cookbooks frequently speak to historical contexts beyond just foodways per se. Especially for 19th or early 20th century time frames, where interviews are no longer a viable means of gathering information, cookbooks of the sort housed in the Lupton Collection provide an invaluable resource for scholars of folklore. After all, one of the central projects of folklore is to train attention on the traditions, everyday lives, and cultural values of so-called ordinary Americans—those whose experiences might not otherwise find their way into the arena of academic study or wider consideration.

Bearing these objectives in mind, students spent the bulk of our afternoon at Hoole carefully analyzing the cookbooks themselves. In preparation for the assignment, Hoole Special Collections CLIR Postdoctoral Fellow Amy Chen pulled a set of cookbooks that I selected from the Lupton catalog in advance.

Once at Hoole, I asked students to select one cookbook from this assortment of options and spend about 45 minutes gleaning as much information as they could from its pages and writing down some reflections on what they discovered. For the remainder of the class period, seminar participants then traded turns presenting their findings to the group and receiving feedback from myself, Amy, and their classmates.

The forthcoming Cool@Hoole blog posts on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday will detail the findings of three of my seminar students: Samm Banks, Emily Tarvin, and Laci Thompson.