Have you ever heard of yellow fever? If you haven’t, give some of the credit to Dr. William Crawford Gorgas. In the early 20th century, following up on the work of Drs. Carlos Finlay and Walter Reed and others, he employed numerous sanitation techniques to dramatically cut down on the incidence of yellow fever in first Cuba, then the Panama Canal zone.

Gorgas became especially interested in the disease, which was also known as “yellow jack,” while he was serving in the U.S. Army Medical Corps. As someone who had contracted yellow fever and survived it — enduring the fever, chills, nausea, pain, and jaundice it could bring — his natural immunity meant he was often called on to take care of yellow fever patients during later outbreaks. When the U.S. went to war with the Spanish in Cuba, yellow fever became a major concern and focus of Army medical research, which brought Gorgas front and center.

The massive W. C. Gorgas collection contains a lot of information about Gorgas’s work in the Panama Canal zone, which he’s best known for, but it also details his learning experiences in Cuba, including his interactions with Reed and Finlay. Here are some examples and highlights.

Carlos Finlay

We take for granted that many diseases are caused by bacteria and viruses — that is, germs. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, this was still a new concept. How those germs were transmitted was even less understood.

In 1881, Carlos Finlay, a Cuban doctor, began arguing that yellow fever was transmitted by mosquitoes.

It wasn’t easy believing this hypothesis, even for medical professionals. In a 1902 report to the Philadelphia Medical Journal, Gorgas details various experiments made in Cuba that helped prove the hypothesis true, as well as his evolving attitudes based in part on observations of his own medical practice.

Finlay’s mosquito hypothesis had first come to the attention of the U.S. government at the outset of the Spanish-American War (1898), when thousands of U.S. troops would be traveling to Cuba.

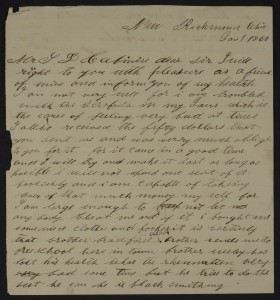

You can read Gorgas’s letters and diary entries from that year here.

Gorgas worked with Finlay in Cuba from 1898 to 1902. After he moved on, he kept well abreast of Finlay’s continued work there, as evidenced in a letter of May 11, 1906. An excerpt:

We plume ourselves upon the way in which our people [the U.S. Army] handled yellow fever in New Orleans last year, and it was very creditably done, but in Havana you limited the disease to much narrower lines and confined it to a much smaller population without any assistance from cold weather or frosts. But what I think is the greatest feather in the cap of the Cuban Sanitary Department is the practical extinction of malarial fever in Havana.

At the time he wrote that letter, Gorgas was already at the Panama Canal site, where both yellow fever and malaria (also transmitted by mosquitoes) had once run rampant. The toll taken by those diseases were part of why the French had had to abandon the project. Gorgas’s work, based in part on Finlay’s hypothesis, brought about a reduction in yellow fever and malaria deaths in Panama, which allowed the canal to finally be completed in 1914.

For more correspondence between Finlay and Gorgas, follow this link.

Walter Reed

Dr. Walter Reed has been sent to Cuba in 1898 to investigate the typhoid fever epidemic among servicemen during the Spanish-American war, but he soon took up the equally distressing problem of yellow fever. At first, they thought the disease was transmitted in much the same way typhoid was, through water contaminated by insects.

Combating yellow fever wasn’t a straightforward thing, even after doctors and scientists concluded that it was transmitted by mosquitoes directly. Many experiments were undertaken in Cuba, including some brave but (to modern sensibilities) ethically questionable trials on human subjects.

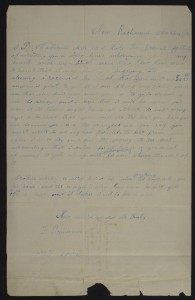

In a letter to Reed in late summer 1901, written when Gorgas was in Havana, he talks about such an experiment. Mosquitoes were allowed to bite an infected man, then those mosquitoes bit seven healthy people. Of the six who came down with yellow fever, half died. Gorgas found the lack of progress frustrating and the loss of life hard to accept:

I am very much disappointed. I had hoped, that through the mosquito, we had a means of giving mild cases which would protect; but these cases show that the severest form of yellow fever can be transmitted by one or two mosquito bites.

I suppose I ought to be thankful for the immense good that the discovery so far has done, and for the great success that our work, this year, has had; but the death of these patients just now, makes all success taste of gall and wormwood, and casts a gloom over the Sanitary Department.

You can read Reed’s reply in Acumen.

Reed and Gorgas spent a lot of time discussing how to rid Cuba of the mosquito menace. In April 1901, Gorgas describes his methods for getting rid of the insects — by draining away the standing water they liked to breed in. In June 1901, Reed urges him not to depend solely on killing mosquitoes but also to work on protecting people from being bitten.

In May 1901, Reed writes to Gorgas to argue that a single bite could give someone yellow fever; it did not take multiple bites, as Finlay and others argued. It wasn’t the only time Reed disagreed with Finlay’s ideas or his seemingly more primitive methods, and in fact there is still some amount of controversy today about where the credit lies for solving the yellow fever problem. However, it is clear that both Gorgas and Reed owed much to Finlay’s early findings and continued work as a sanitary officer.

Reed, despite his forceful personality, seems to have had a good sense of humor, and to have developed professional respect and genuine affection for both Gorgas and Finlay. Right up until his death in November 1902, Reed continued to correspond with Gorgas, inquiring about the state of yellow fever in Havana and working out new and better ways to tackle the epidemic.

For more correspondence between Reed and Gorgas, follow this link.

Great Spirits, Restless Souls

In September 1915, a couple of weeks after Finlay’s passing, Gorgas gave a eulogy for him at a meeting of the American Public Health Association. In summing up his character, Gorgas said:

He was a most genial, kindly, modest man, but strong and determined when he thought any matter of principle was involved.

Gorgas imagines Finlay and Reed, two “great spirits,” meeting in the afterlife, but he says he will not tell them to rest in peace:

I know such souls do not desire to rest in peace but are continuing development along the altruistic lines which they so preeminently adorned in this life.

In 1914, Gorgas was appointed Surgeon General of the U.S. Army. Before he died in 1920, he was even given an honorary knighthood by King George V of the United Kingdom. His methods didn’t just improve the Panama Canal zone; they were a model used by other healthcare workers all over the world. His personal and professional relationships with Carlos Finlay and Walter Reed and their experiences fighting yellow jack in Cuba were instrumental in making these methods a reality.

Interested in more about Gorgas’s connection to the Panama Canal?

- If you’re searching online, you can find more letters and reports in Acumen.

- If you’re here on campus, why not visit the Gorgas House Museum, where there is now an exhibit on his time in the Panama Canal zone. Admission is free for students, faculty, and staff, and just $2 for visitors.