Over the course of this semester, Brett and I have been challenging our instruction students to create and refine active learning exercise that they can use in class as part of their instruction training. The University of Alabama highly values active learning, and without it students tend to get lost in the new environment (the library’s instruction lab) with a new face (the instruction librarian). Our design goals for active learning exercises have been to provide students with the opportunity to engage with the content using their critical thinking skills.

Because we’ve asked them to design new exercises every week, and the three of them have amassed quite a library of activities. Over the past two weeks, they have had the opportunity to try their exercises out in the classroom to see what works and what doesn’t and have had the opportunity to refine their exercises accordingly.

I wanted to share a few examples of the activities that have been produced this semester. They are simple, and something that I like about both of them is that they ask students to take responsibility for their own learning.

The first is a Web Evaluation exercise that Karlie has created:

This exercise was created for use in an EN101 class. UA’s EN101 doesn’t have a large outside sources requirement, and for the one paper they do use outside sources for they usually let students use websites. The point of the paper is to teach students to synthesis information. Karlie’s exercise gives students clear guidelines for judging a website for authority and intent, which is the critical thinking component of the exercise, rather than giving them a set of rules based on domain. The exercise is completed in conjunction with a short (15 minute) class discussion about domain, authorship, intent and publication process.

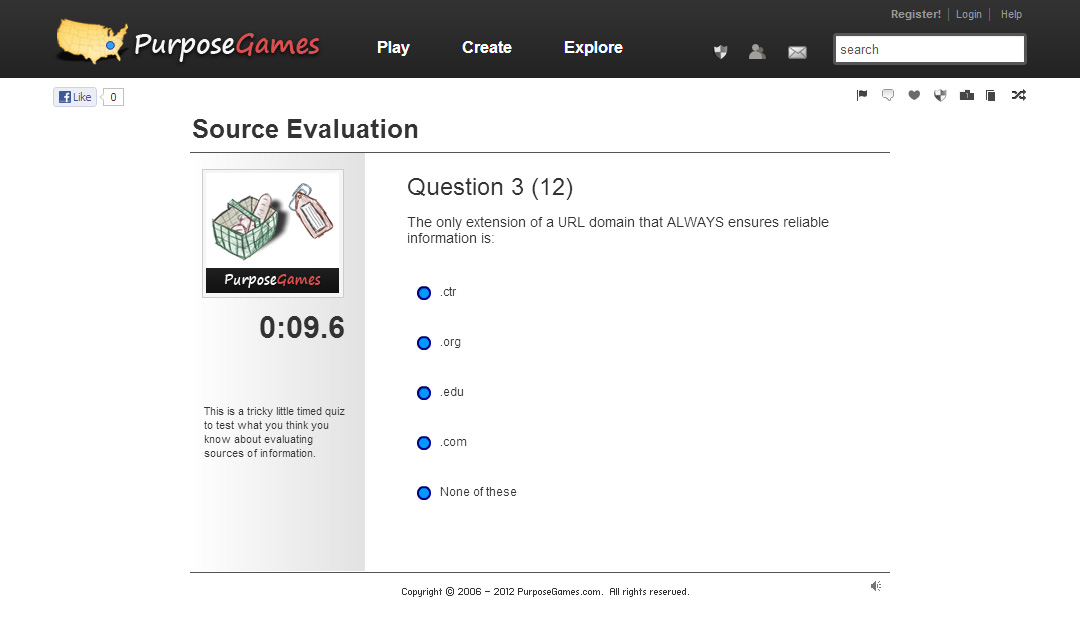

The second exercise I’d like to share with you is Louise’s Source Evaluation game (you will have to follow the link to see the full game).

This game has been a great tool to engage students in a meta-cognitive practice before talking to them about source evaluation during session 2 for EN102 classes. She allows students to play the game as their first activity in class, and then engages them in a 15 minute theoretical talk about scholarly and popular sources. Because they have measured their incoming knowledge, students are aware of what they know and what they need to know before any discussion begins.

The exercises that Karlie, Louise and Alex have designed are being used very successfully in the classroom. When we asked them to begin designing them, it was my intention that we create a pool of activities that can be used by anyone in our department (there are 9 instruction librarians currently in our department). We will maintain this pool and continue to add next semester with our new interns and GTAs. I think it will be great for them, during their job searches, to be able to say that they contributed to a departmental instructional activity repository, and it is going to be quite useful for our department as well, as we seek to serve our 6400 new freshmen by providing them interesting and informative experiences at the library!