By: Amy Chen, CLIR Postdoctoral Fellow

During the month of December, “Covering Christmas: Publishers’ Bindings at The University of Alabama” will be on display in the lobby of the Mary Harmon Bryant Building and in a case in front of the Capstone Drive entrance of the Amelia Gayle Gorgas Library.

All items from this exhibition belong to the Division of Special Collections at The University of Alabama. Additionally, each of these items is represented in the database Publishers’ Bindings Online (PBO). PBO foregrounds how decorative bindings provide a look into culture and history of the era of 1815-1930, a time of social, political, and industrial change within the United States, by giving users the ability to view around 5,000 different bindings from the holdings of the W.S. Hoole Library at The University of Alabama and Special Collections at The University of Wisconsin. Each of the books shown here come from either the Wade Hall Collection for Southern History and Culture or the Alabama Collection at Hoole.

Ranging from 1898 to 1921, these publishers’ bindings celebrate Christmas in a variety of ways depending on the years they were produced, the artists that created the designs, the content of the books, and the style of the times.

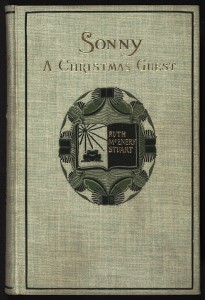

For example, ragtime music, yellow journalism, mass circulation magazines, and national advertising campaigns defined the prosperous 1890s. Publishers’ bindings from the 1890s usually were multicolored and flat-stamped. Artists became essential to publishing houses at this time. A select few, such as Frank Hazenplug, became well-known. A later example of Hazenplug’s work can be seen on Sonny: A Christmas Guest (1905).

At the turn of the century, the social problems of modernity increasingly began to be identified and debated, but light-hearted entertainment also had a place in the lives of Americans. As women’s skirts grew shorter, The Ford Model T car and Victrola phonograph became all the rage. In the book world, paper dust jackets began to be produced to match the ever-more elaborate publishers’ bindings.

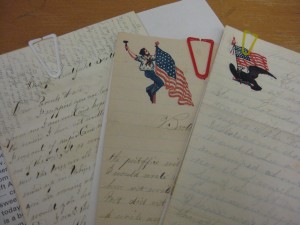

From 1910-1919, World War I dominated headlines. In 1917, the United States joined the fight. Due to the United States’ ability to mobilize and mass produce supplies for the battleground, this decade shaped America into the international superpower it is today. The diversity of publishers’ bindings of this era reflects the spread of inexpensive dust jackets and more efficient publishing methods. Whether at war or at home, American culture began to reflect an increasing emphasis on satisfying the growing number of mass market consumers.

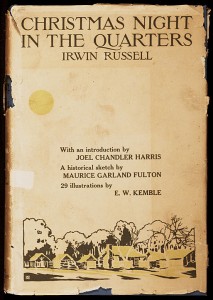

The firm Decorative Designers took the idea of standardization from Henry Ford. Instead of employing one artist to make an entire cover, the firm chose to hire a number of designers who each made one portion of a binding. Decorative Designers created Christmas-night in the quarters (1917), which can be seen here.

The freewheeling 1920s, which began with the ratification of women’s right to vote and Prohibition, ended the time of the publishers’ binding as dust jackets became ubiquitous.

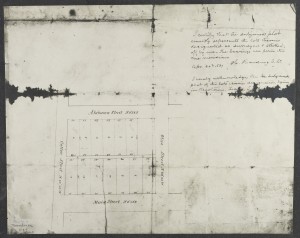

Items on display include:

William Aspenwall Bradley. Old Christmas and Other Kentucky Tales in Verse. Boston, MA: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1917. Wade Hall Collection PS3503.R226 O4 1917x

John Fox. Christmas Eve on Lonesome. New York, NY: Grosset and Dunlap, 1904. Wade Hall Collection PS3511.O95 C5 1904x

Maud Lindsay. The Joyous Guests. Chicago, IL: E. M. Hale, 1921. Alabama Collection PZ7.L66 Ja

Thomas Nelson Page. A Captured Santa Claus. New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1905. Wade Hall Collection PS2514 .C3 1905x

Irwin Russell. Christmas-night in the quarters, and other poems. New York, NY: The Century Company, 1917. Wade Hall Collection PS2740 .A2 1917 c.2

Francis Hopkinson Smith. Colonel Carter’s Christmas. New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1903. Wade Hall Collection PS2864 .C642 1903bx

Ruth McEnery Stuart. Sonny: A Christmas Guest. New York, NY: The Century Company, 1905. Wade Hall Collection PS2960 .S62 1905x