By: Lindsay Smith, Melissa Young, and Rachel K. Deale, History PhD students, and Amy Chen, CLIR Postdoctoral Fellow

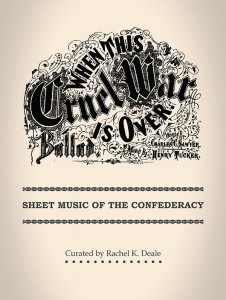

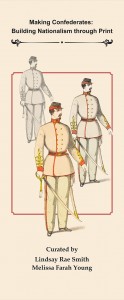

This post is the final entry in a five-part series titled “Curating the Confederacy: An Interview with the curators of Making Confederates and When this Cruel War is Over.” If you haven’t yet, please read the first, second, third, and fourth installments of this series.

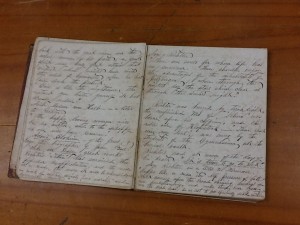

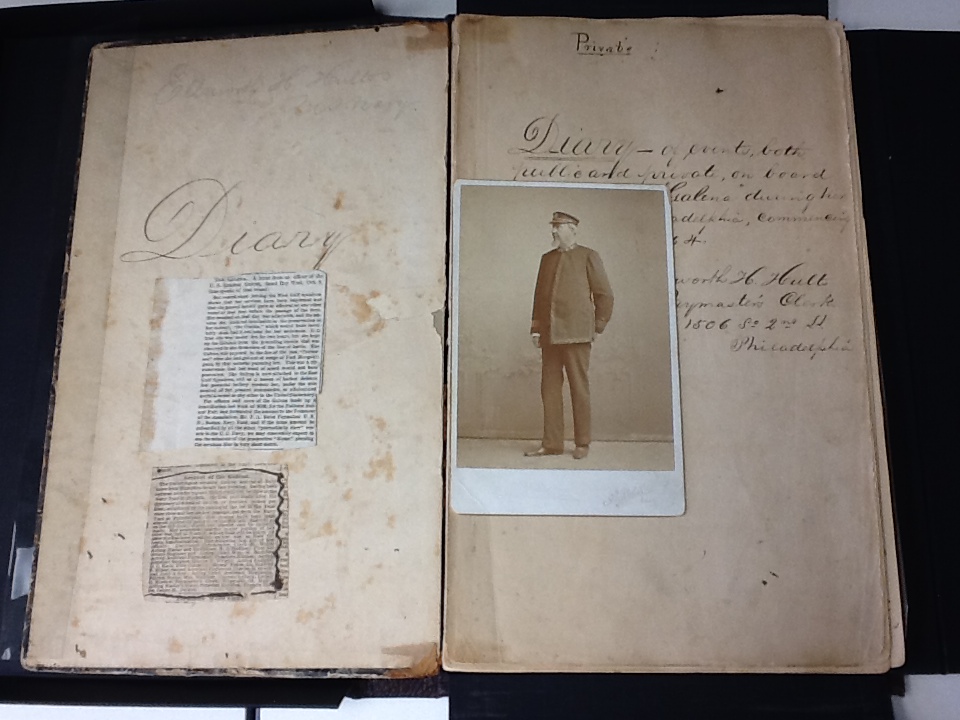

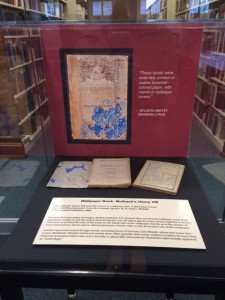

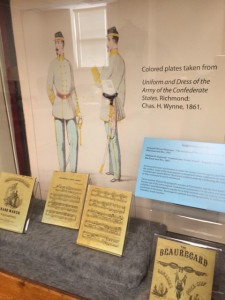

Display case from Making Confederates, currently on display in the A.S. Williams III Americana Collection

What would you say to future students who might have the opportunity to create exhibitions within the library with special collections holdings? Do you have any advice to share?

Rachel: I would definitely recommend that they take advantage of the opportunity. When you are getting started I think that it is important to make sure you choose a topic that is not too narrow or too broad. Try to focus your exhibit on a simple, but well focused topic or theme. I also think that it is very important to always keep your display cases and space in mind as you are researching the collection. Imagining how you plan to display the items as you go along is makes it easier to decide how you will organize and present your argument.

Lindsay: First, I would highly encourage them to take the opportunity. It’s a lot of fun and a nice change of pace from academia history. The process of putting together an exhibit is very hands on and inherently creative, I think. I would, however, recommend that you are interested in the exhibit’s topic because you will know a lot about it when you are done.

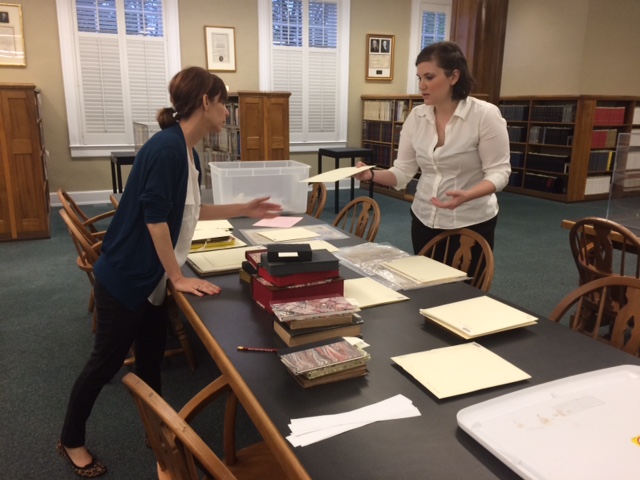

Melissa: The only advice I might share is to manage your time wisely and utilize the fabulous librarians because they are huge sources of knowledge. Lindsay and I started working on the project early, in December, so that we could become familiar with the holdings before we had additional responsibilities. This allowed us to generated an argument and narrow our focus quite early. We worked around one another’s schedules and personal deadlines and kept communication lines open—one of us would dedicate more time to the exhibition if the other had to study or work on a paper. We also spoke to Jennifer Cabanero and Nancy DuPree at length many times. They pointed out some really great items and offered new perspectives on some of the ones we had already chosen, especially after they knew the direction we wanted to follow. Jennifer and Nancy were also incredibly supportive and shared in some of the excitement of our own finds. To prevent being overwhelmed, students should stick to a schedule and look to each other and the librarians for assistance and guidance. That way it will be much easier to relax and enjoy the project as much as we did.

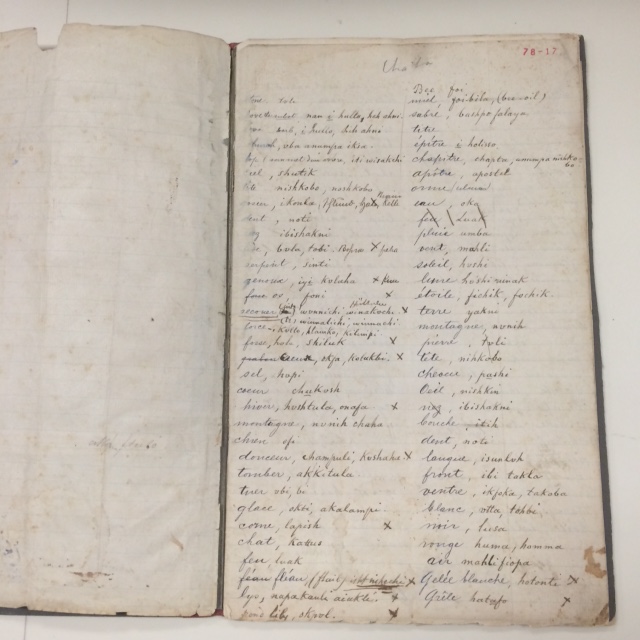

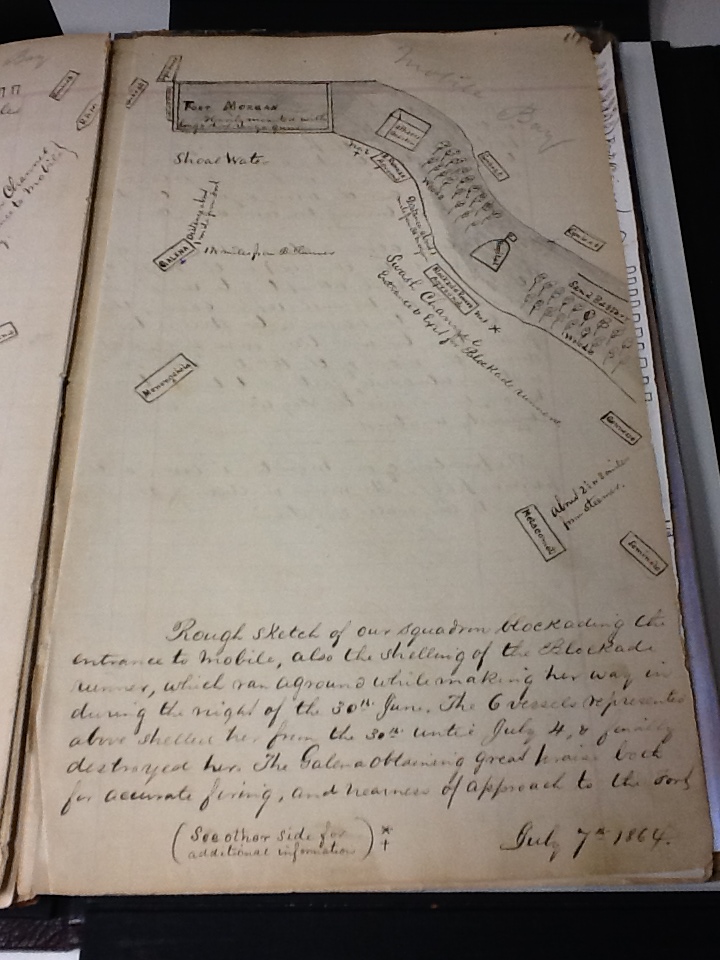

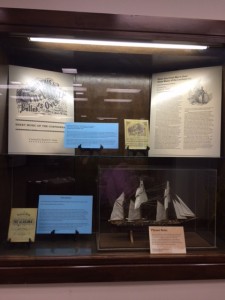

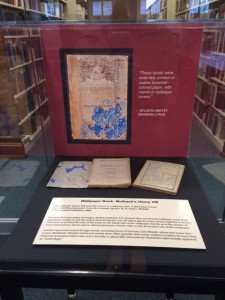

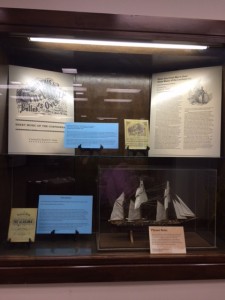

Case from When this Cruel War is Over, currently on display in the W.S. Hoole Library

What sort of role would you like to see yourself in following your graduation from the University of Alabama?

Rachel: I hope to teach at a liberal arts college or university. I would also enjoy working as an editor for an academic journal or press.

Lindsay: I am still very much interested in pursuing a career in academic history. However, I see myself working at a smaller liberal arts college that allows me the flexibility to teach a lot of different courses, pursue my research interests, and also to work closely with the libraries and local historical museums. I enjoy public history too much to give it up completely.

Melissa: Although I would love to teach at the post-secondary level, I would also like to pursue a career in a history museum or in an organization that promotes historical awareness. I have interned at small rural house museums and large urban institutions like the Birmingham Museum of Art. Both experiences were wonderful in very different ways, so I could see myself working in either type of institution. My own research is also very important to me. Hopefully I can continue to incorporate Civil War history, gender studies, and language in some of what I do, but if I go in another direction, I am okay with that. I love learning new things and gaining additional knowledge, so I am open to other historical genres, especially local ones. I may have the opportunity to work with the Birmingham Holocaust Education Center this summer, for example, which is really exciting. I have also recently started studying Latin American history and am going to Brazil in August. I hope to eventually be able to share some of my knowledge and experience with future students or museum guests.

Amy: Thank you for sharing your knowledge, experience, and insights with us today on Cool@Hoole. We encourage our readers to come see Making Confederates in Williams and When this Cruel War is Over in Hoole between April and September 2015.

Please don’t hesitate to tweet us about #makingconfederates and #thiscruelwar @coolathoole! Follow @coolathoole on Facebook and Twitter to get sneak peeks of items on display for the two weeks following the opening of these exhibitions (April 13-May 1).

Additionally, to continue our promotion of these shows, next week on Cool@Hoole we will share the curatorial essays from each exhibition. That way, if you are not able to come to campus, you can still get a taste of the content Rachel, Lindsay, and Melissa developed.