By: Lindsay Smith, Melissa Young, and Rachel K. Deale, History PhD students, and Amy Chen, CLIR Postdoctoral Fellow

This post is the second in a five-part series titled “Curating the Confederacy: An Interview with the curators of Making Confederates and When this Cruel War is Over.” Read the first installment here.

In what way did your exhibition’s topic depart from the type of research you usually pursue?

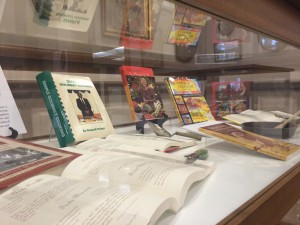

Website for the American Civil War portion of the A.S. Williams III Americana Collection

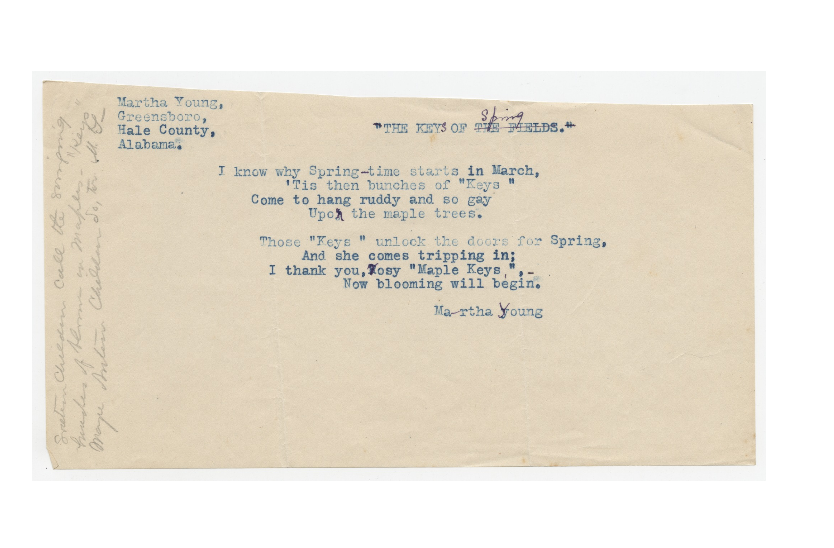

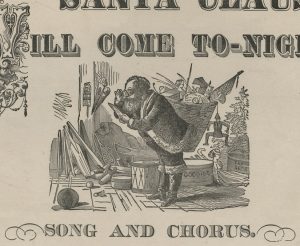

Rachel: Most all of my sources for my dissertation are government documents, governors’ papers, newspapers, diaries, and political correspondence. While most of the sheet music included in my exhibit is very political, examining cultural sources was a pleasant departure. My dissertation also only focuses on the few months preceding the war, so it was a nice change of pace to explore Confederate music that was written throughout the entire war.

Lindsay: Because the Williams Collection houses so many Confederate imprints, the exhibition blends the government and military documents that circulated among politicians and soldiers with the novels, music, and textbooks that women, children, and nonmilitary personnel would might have read. Because I am interested in the medical aspect of the war, I tend to write more about soldiers and the battlefield than civilians the home front, so it was fun to explore the popular literature of the time.

Melissa: I study the language of Union soldiers who were garrisoned in the South, and my research concentrates on concepts of nineteenth-century masculinity and femininity. Because my work is generated from the manuscripts of northern men, I often don’t have the opportunity to directly examine many Confederate materials or items produced by women. As someone who studies the Civil War, I was familiar with the context of what we were examining, the concept of imagined nationality, and Confederate nationalism in general. My knowledge base, however, had been formed on secondary sources that quoted some of the things we found in the archives. It was great to examine the actual words of southern nationalists, to flip a page and see something exciting that reinforced the story we wanted to tell. Some Confederates’ language was brilliant, some highly offensive, but all of it was extremely interesting!

ten Hoor Hall, location of the UA History department

Creating an exhibition for a library can be seen as a project belonging to the field of public history, rather than academic history. Did you feel you had to change your approach to history in order to share your content with a broader audience? Or, if not, why did public history overlap so much with a more academic approach to the discipline?

Rachel: As Carl Becker said in his famous address “History is the memory of things said and done.” History is a universal discipline in that all humans naturally reflect on their past. I believe that good history is clear enough for the general public to understand it. In other words it is possible to have a sophisticated analysis and argument that is also widely accessible to the public. I think that it is important for professional historians to remember that history is only useful if it is in people’s minds. Like Becker wrote, “the historical fact is in someone’s mind, or it is nowhere, because when it is in no one’s mind it lies in the records inert, incapable of making a difference in the world.” It is the professional historians’ job to present the past in a clear, coherent, and meaningful way to the general public. Nevertheless, it did feel wrong not to cite where I found my information for my captions and curatorial essay. Christian McWhirter’s Battle Hymns: The Power and Popularity of Music in the Civil War was the most helpful source for my exhibition. Without McWhirter’s book it would have been near impossible for me to create my exhibition in the time we had.

Lindsay: Oh definitely. I actually got my start with public history working at Vicksburg National Military Park and the way you have to interact with the information is very different. As a curator, my job is to learn everything I can about a topic, in this case the Confederate imprints. However, my ultimate goal is to condense what I know to the most essential (and interesting) parts in order to convey that to whoever visits the exhibition. It’s actually quite a bit like teaching, except I am allowed to tell this story through actual objects.

Melissa: I think we attempted to be aware we were creating an exhibition designed specifically for public consumption, but we did not change our approach to history. Academic and public history often overlap, so I don’t really see them as mutually exclusive. I think they can inform each other. Historians tend to get caught up in writing and speaking to each other. Sometimes we may need to take time to step back and adjust our style of delivery for a wider audience. That is what history is really all about—if you can’t present your ideas well, no matter how academic, they are not truly effective. I also think it is important to allow the public to “hear” the voices of the past, without “candy-coating” or attempting to censor them. We may not agree with what is being said, but it is up to each person that sees the exhibition to form his or her own opinion about the documents that are displayed and the people who are featured.

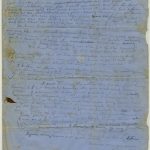

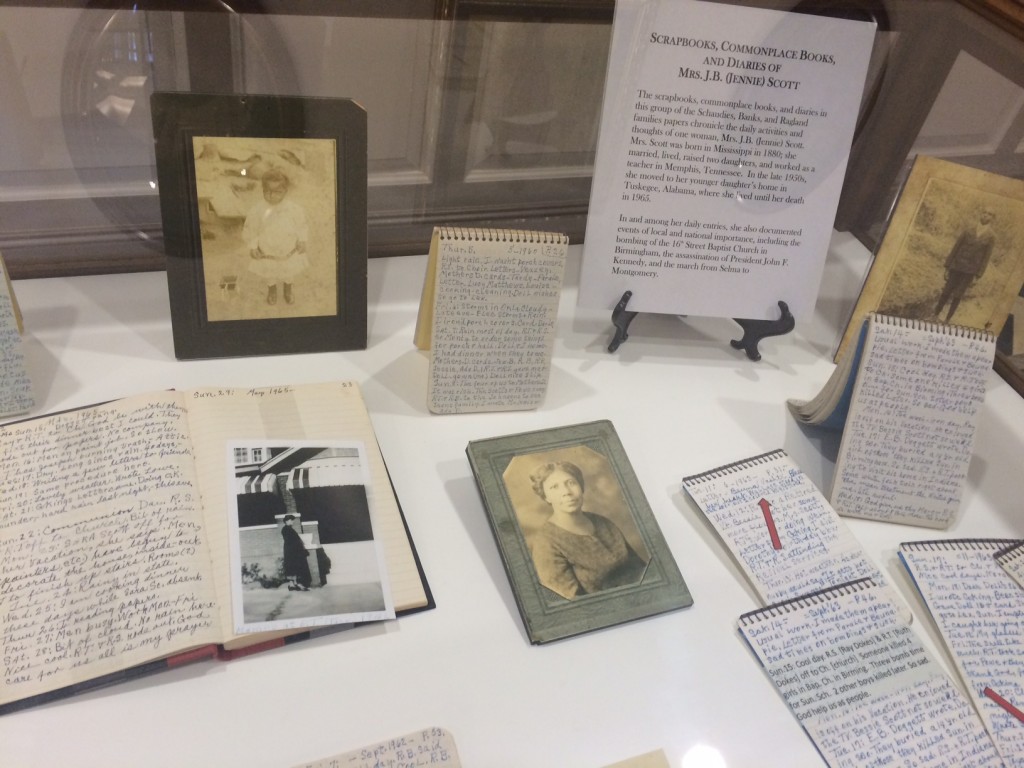

miscellaneous writings (some appear to be school related), newspaper clippings, recipes, and poems. There is also a typed transcription of the book, which was perhaps provided by the donor.

miscellaneous writings (some appear to be school related), newspaper clippings, recipes, and poems. There is also a typed transcription of the book, which was perhaps provided by the donor. Consists of three bound volumes of this Alabama attorney and politician and his wife: John Cochran’s diary; Mary Wellborn Cochran’s journal; and a miscellany of copies of some of John Cochran’s outgoing correspondence, journal entries of his, and copies of some freedman contracts to which he was party. Also includes two unidentified photographs that appear to be from the early twentieth century.

Consists of three bound volumes of this Alabama attorney and politician and his wife: John Cochran’s diary; Mary Wellborn Cochran’s journal; and a miscellany of copies of some of John Cochran’s outgoing correspondence, journal entries of his, and copies of some freedman contracts to which he was party. Also includes two unidentified photographs that appear to be from the early twentieth century. Consists of over one hundred documents relating to the Mississippi and Alabama plantations of brothers William and Crawford L. Brown. The documents include bills of sale for slaves; receipts for clothing, dry goods, and tool repair; tax receipts listing the number of slaves; bills of lading for cotton bales; and business letters.

Consists of over one hundred documents relating to the Mississippi and Alabama plantations of brothers William and Crawford L. Brown. The documents include bills of sale for slaves; receipts for clothing, dry goods, and tool repair; tax receipts listing the number of slaves; bills of lading for cotton bales; and business letters. Contains Civil War letters and miscellaneous documents of James Franklin Holliman and William Stewart, to and from their families between 1862-1911, and relating to Fayette County, Alabama, history. The majority of the letters are from the Civil War era.

Contains Civil War letters and miscellaneous documents of James Franklin Holliman and William Stewart, to and from their families between 1862-1911, and relating to Fayette County, Alabama, history. The majority of the letters are from the Civil War era. Contains the personal letters and war-related correspondence of Brigadier General George Doherty Johnston of the Twenty-fifth Alabama Infantry, C.S.A. The majority of the letters are from his first wife, Euphradia, and his mother.

Contains the personal letters and war-related correspondence of Brigadier General George Doherty Johnston of the Twenty-fifth Alabama Infantry, C.S.A. The majority of the letters are from his first wife, Euphradia, and his mother. Contains Friedman’s personal and official correspondence, photographs of a camp in the Alps, his lieutenant’s commission, his Croce al Merito di Guerra and other military pins and ribbons, and various items issued to him by the military. Incoming correspondence is arranged alphabetically by author’s surname, and outgoing correspondence is arranged chronologically.

Contains Friedman’s personal and official correspondence, photographs of a camp in the Alps, his lieutenant’s commission, his Croce al Merito di Guerra and other military pins and ribbons, and various items issued to him by the military. Incoming correspondence is arranged alphabetically by author’s surname, and outgoing correspondence is arranged chronologically. he collection contains letters and postcards of Hans Höchersteiger, a technical sergeant of the Luftwaffe during World War II. Höchersteiger was captured in May 1941 and was held first in England and then in Ottawa, Canada. All the letters and postcards from Höchersteiger are to his family in Stuttgart, Germany, and are written in German. There is no translation for them at this time.

he collection contains letters and postcards of Hans Höchersteiger, a technical sergeant of the Luftwaffe during World War II. Höchersteiger was captured in May 1941 and was held first in England and then in Ottawa, Canada. All the letters and postcards from Höchersteiger are to his family in Stuttgart, Germany, and are written in German. There is no translation for them at this time.