Philology, n. the study of literary texts and of written records; linguistics, especially historical and comparative linguistics; Obsolete: the love of learning and literature.

Long before literature students spent their time looking for symbolism and theme in poems and stories, the study of literature was about appreciating the beauty of the language and sentiment in literary texts. Along with this came a serious study of the linguistic roots of texts, or just linguistics in general — how English came to be the way it is, and how it works.

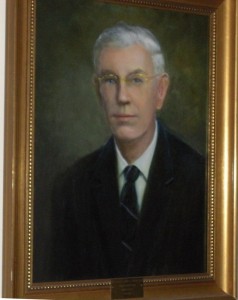

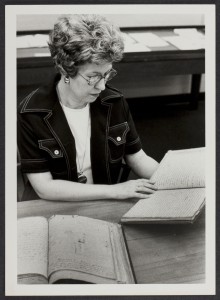

All these definitions of Philology come into play in a lecture notebook from Professor Benjamin Franklin Meek, from the 1872-1873 school year. Meek taught Latin and Greek at UA during the 1860s and literature from the 1870s to his death in 1899.

Linguistics

Meek begins all the way back at the Roman occupation of England and its influence on the “Celtic tongue,” tracing English through the Saxon invasions, the influx of Danish peoples, and finally the Norman conquest, when Old English crashed into Old French.

He goes so far as to show a table of the proportion of Saxon words in the writings of major authors to date:

Translating the Bible into English

After this history lesson, he takes up the topic of the Christian Bible: “for no work in the language, viewed simply as a literary production, has had a more profound historical influence over the world of English speaking people.” He discusses the various ancient translations (such as the Septuagint and Vulgate) that eventually led to English versions of the Bible like the Douay–Rheims and more familiar King James versions.

Major Authors

A further section of the notebook contains commentary on specific parts of the course textbook, referencing works like Piers Plowman and Paradise Lost, and writers like Ben Jonson, Alexander Pope, and Daniel Defoe. Also referenced were physicist Isaac Newton and theologian/hymn writer Isaac Watts, showing that philosophical writings were also important to the study of literature in the 19th c.

American Literature?

As expected, little attention is given to American Literature as a whole, which didn’t gain a foothold in the academy until the 20th c. But he does include specific American writers like Washington Irving, James Fenimore Cooper, and Nathaniel Hawthorne among his major authors. Here are his comments on Edgar Allan Poe, to whom he says “the text[book] does not do justice”:

Shakespeare and Linguistics

The remainder of the book is given over to “Lectures on the English of Shakespeare,” which uses Shakespeare’s works to talk about the differences between Elizabethan and Victorian (then-modern) English.

Exam

On the inside back cover you find an examination given to the senior class in February 1873. I happen to have a PhD in Anglo-American literature, but the study of literature has changed so much that there’s no way I would pass this exam… as you’ll see below with my no-cheating, off-the-cuff answers.

1. They were Celtic peoples?

2. The Romans brought Latin, Saxon exerted a major influence on the native Celtic language which is still seen today (especially in our expletives), I have no idea how the Danes influenced us, and the Normans brought French, which changed the structure of our language a lot (made it less germanic and more latin) and contributed a lot of words.

3. ???

4. ???

5. [I know how we divide periods now, but then?]

6. Edmund Spenser helped popularize the sonnet in English and wrote The Fairie Queen, an allegorical epic poem in iambic pentameter, with just enough hexameter to make it really tedious to read.

7. [If I answered the first part of this I would be cheating, since I read the names as I perused Meek’s notes.] The King James version was commissioned by King James I of England, based on the Latin Vulgate. It is a word-for-word translation, rather than a sense-for-sense translation.

8. He was born in the 18th century and died in the 19th century. He wrote historical novels like Ivanhoe.

9. [Once again, I would be cheating to answer this, although I probably would’ve guessed correctly.]

10. (1) ???, (2) Thomas More, (3) Dryden?, (4) ???, (5) Poe

How did I do? 🙂