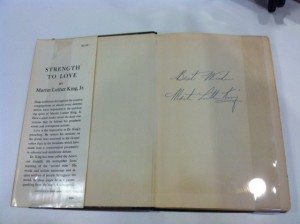

The Alabama Gang by Clyde Bolton

By: Allyson Holliday, W.S. Hoole Library Complex Copy-Cataloger

In honor of the NASCAR Hall of Fame’s 2014 induction ceremony this week, the blog spotlight belongs to Alabama’s own Bobby Allison – a 2011 inductee.

So what is the “Alabama Gang”? The original “Alabama Gang” consisted of auto racers Red Farmer and the Allison brothers, Bobby and Donnie. The trio traveled to short tracks all over the southeastern United States together and frequently claimed the top three positions in their races. One evening in the 1960s, as they arrived at a race track in the Carolinas, a local moaned, “Oh, no, there comes that Alabama gang,” and their nickname was born (Bolton, 4). The term “Alabama Gang” would later be expanded to include all race car drivers from Alabama.

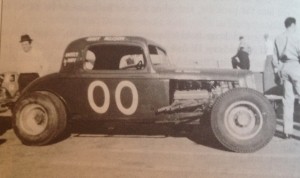

Robert Arthur “Bobby” Allison was born in Miami, Florida, in 1937. His racing career brought him to Alabama permanently in 1961 to race in NASCAR’S Modified-Special Division. First living in Bessemer, Bobby and his family later settled in neighboring Hueytown. From his base in Hueytown, he found immediate success winning the Modified-Specials Division titles in 1962 and 1963, which mostly raced in Alabama and Tennessee. Even a switch to the standard Modified cars did not stop his winning streak. Bobby won the 1964 and 1965 national championship in that division (Bolton, 30).

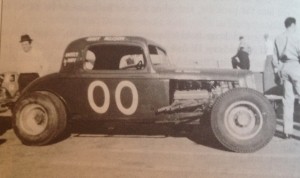

One of Bobby Allison’s early modified special racers, photo from Clyde Bolton’s The Alabama Gang

Bobby graduated to the big leagues when he began, in 1966, his NASCAR Grand National/Winston Cup career (Golenbock, dust jacket). He had made it to stock car racing’s biggest stage. And he took full advantage. He would go on to win 84 races and capture 58 poles before he retired in 1988 after an accident at Pocono Raceway that nearly took his life. He finished his career tied for third on the all-time victory list with Darrell Waltrip. Despite his prolific winning record, Bobby only won a Winston Cup championship once – in 1983.

As a member of the “Alabama Gang” and to celebrate his racing career, Bobby was inducted into the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame in 1984. Fittingly, Bobby was also named one of NASCAR’s “50 Greatest Drivers” in 1998.

Bobby Allison holds up his belt buckle for winning the NASCAR championship in 1983, from Peter Golenbock’s Miracle: Bobby Allison and the Saga of the Alabama Gang

After his last race and accident at Pocono Raceway, he battled a significant brain injury that led to memory loss and difficulty completing everyday tasks. While recovering from his extensive injuries, his focus turned to the racing careers of his sons, Clifford and Davey. Bobby also returned to NASCAR as a race team owner in 1990 forming Bobby Allison Motorsports (Golenbock, 270). Responding to a reporter about his new role, Allison said, “Owning a car is not as good as driving, but it’s way better than lying in a hospital bed” (271). Bobby was very lucky to survive the injuries he sustained in his last race and NASCAR narrowly avoided a tragedy.

However, tragedy struck the Allison family all too soon. On August 13, 1992, Clifford Allison was driving for his dad’s Busch Grand National team at the Michigan International Speedway when his car spun and hit the wall in a practice session. He was killed instantly. Then, in July, 1993, the unthinkable happened.

Davey was flying his helicopter to Talladega Superspeedway to watch Neil Bonnett (a fellow Alabama Gang member) test, when the chopper crashed. Red Farmer, a member of the original Alabama Gang, survived the crash with broken bones but Davey suffered massive head injuries. Recalling the miracle survival of Bobby just five years earlier, many thought Davey would come through this and maybe one day return to racing and join his father as one of NASCAR’s greatest drivers. It was not to be. On the morning of July 13, 1993, exactly eleven months to the day of Clifford’s death, Davey Allison passed away at the age of 32.

It is hard to imagine how Bobby Allison endured that stretch in his life. He closed Bobby Allison Motorsports in 1996 but has remained a beloved figure in the NASCAR world. Asked how he survived it all, Bobby replied, “My life has been a series of ups and downs, hills and valleys, top of the mountain, bottom of the valley…I had really, really good times, and I had disasters, where other people might have quit racing, but every time I hit a valley, I figured there had to be another hill out there and I’d climb that hill. I’ve been blessed in so many ways. And I’m grateful” (Golenbock, 386).

The Allisons are racing family royalty and Bobby is still seen around the NASCAR circuit at different races and events. My family and I had the pleasure of meeting him before a race at Talladega Superspeedway in 2011. A quintessential, southern gentleman with an enduring passion for life and the sport he loves – through triumph and tragedy.

Works Cited:

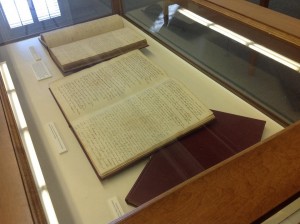

Clyde Bolton. The Alabama Gang. Birmingham, AL: Birmingham News, 1994. Hoole Alabama Library Collection GV1032.A1 B65 1994x.

Peter Golenbach. Miracle: Bobby Allison and the Saga of the Alabama Gang. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2006. Hoole Alabama Library Collection GV1032.A3 G65 2006.