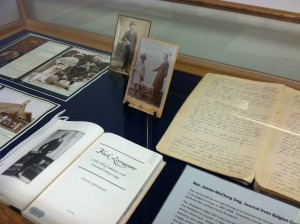

In the 19th century, more and more women became not just occasional novel writers but full time authors. Hoole Special Collections Library houses the papers of Georgia native Augusta Jane Evans Wilson, who published nine sentimental novels, including Beulah, the popular Confederate war novel Macaria, and St. Elmo, a novel so popular it spawned a parody (source: Wikipedia).

The digital collection includes two dozen letters Wilson wrote to her friend Rachel Lyons Heustis, covering personal matters as well as discussion of her writing and of the Civil War, topics which for Wilson were usually heavily entwined.

*

In a letter dated October 17, 1859, Augusta discusses her novel Beulah. Apparently, Rachel had some objections to it, for Augusta writes: “Most especially do I appreciate and prize the affectionate candor which impells you to acquaint me with the various objections urged against my book. Verily, there are numbers to flatter me, but very few sufficiently my friends to tell me honestly of my faults.” Wilson’s response to those questions can be seen below:

In a letter from around the same time, Augusta writes to Rachel upon hearing that she was planning to marry a Jewish doctor. The man was a friend of Augusta’s — she says, “I have no friend whom I should be so glad to see happily married, as Dr. Heustis” — but she follows that up by saying, “I must tell you, that I was very much astonished to find from your letter, that you had no informed your parent of your engagement!” She admonishes Rachel to do so, then she asks:

She later adds, “If you love Dr. Heustis, no one has the right to forbid your marriage.”

In July of 1860, Augusta, unmarried herself, writes to Rachel about women writers and marriage. Apparently, there was a rumor that Rachel had written a novel herself, but Augusta was sure she hadn’t. She says, “I have often wondered why you did not write! Of course you know you could if you would; and my darling you have such a glorious field stretching out before you” — that is, her husband’s Jewish heritage. “Rachel write a Jewish tale; and make it a substratum on which to embroider your views of life, men, women, art, literature.”

Of women writers she has much to say:

(Though she claimed she would never marry, she did so in the years after the war.)

In a letter dated November 13, 1860, Augusta encourages Rachel in her plans to write: “Elaborate the plot, brace clearly to the end your grand leading aim, before you write a line and then you will find no trouble I think, in…the details.” She mentions George Eliot’s novel Adam Bede as a model, calling it “the most popular book of the age.”

She also talks of the impending war:

By the letter of February 2, 1861, the Civil War was just over two months away. Augusta speaks of the ladies of Mobile filling sand bags for nearby Fort Morgan,on Mobile Bay. She says: “My Father and both my Brothers belong to the garrison of Fort Morgan and you can readily imagine, how restless their constant exposure to attack renders me.” She also longs for the secession of other southern states:

On October 3, 1861, she writes of her expectation that the South will win the war:

She goes on to say: “In the thoroughly demoralized and panic=striken condition of the Federal Army subsequent to the battle of Manassas, one bold, vigorous, Napoleonic stroke must have decided the war; and the flames of Washington and Philadelphia, would have furnished light to write the terms of Peace.”

Later, she compares the Civil War to the ancient Second Punic War, picturing the South as Rome and the North as the eventual loser of that war, Carthage. She says, “Rachel, I am haunted by the fear that our leaders lack nerve; that we have No Scipio to carry the war into Africa. For months, the burden of the Southern press has been, delenda est Carthago [Carthage must be destroyed]!” She hopes that they are not, indeed, the Carthage of this conflict, the winner of a major victory but not the war: “I pray Almighty God, that future historians may not record of this our war of Independence, that, Manassas Junction was the Cannae of the Confederate Army.” Unfortunately for the South, it was.

In a letter dated January 22, 1862, Augusta discusses working in a hospital near her home: “Oh! My darling if I could tell you of all I have witnessed, and endured since I became a hosptial nurse!” They treated illnesses like Typhoid Fever and pnuemonia with brandy, ammonia, and quinine.

In September 12, 1863, she updates Rachel on the progress of her newest novel, Macaria, which was eventually a popular work in both the North and South. She also makes many comments on General Beauregard, including the following: “God grant that Beauregard may hold Charleston successfully. If any human being can, he will.”

In a letter dated May 1, 1864, she discusses the reception of Macaria, saying that some have “pronounced it superior to Beulah.” But she seems to still want Rachel to serve as a sounding board for her work: “I trust when you have carefully read it, you will give me your opinion frankly concerning its merits and defects.” The letter also returns to the subject of Rachel’s marriage, Augusta’s hopes that Rachel’s parents have accepted their new Jewish son-in-law:

*

For more on Augusta Jane Evans Wilson, see her entry in Encyclopedia of Alabama.