By guest blogger Alex Olkovsky, a graduate student in American Studies

While many collections in our archives contain business and legal documents, there are also numerous focused on people’s daily and domestic lives. Unsurprisingly, these collections are where we can oftentimes most clearly hear women’s voices. Women’s daily lives, beliefs, and values come through in commonplace books, which are essentially a mixture of diary and scrapbook, often containing journal entries, newspaper clippings, copied poetry and hymns, and recipes.

Looking at these recipes, in particular, can give us more information about the woman, her socioeconomic class, and her location. They can also help us date the book, as the use of certain foods and technologies denotes a particular time period. Plus, we can see which recipes have stood the test of time and which have, fortunately for us, been replaced with cheaper and/or yummier ones.

Two commonplace books in the collection tell a story of how American cookery evolved over the latter half of the 19th century. Martha Jane Coleman Banks’ commonplace book, which she created from around 1848 to around 1865, shows the relative poverty of her time as well as the real concern of how to preserve food in the time before mass refrigeration. Annie Perkins’ book, dated to the early 1910s to the 1920s, shows very different patterns in cooking and food. Her recipes include many more dessert recipes, as well as newer and more expensive ingredients such as coconut, salmon, and oysters, and refrigeration seems less difficult, as her book even includes a recipe for homemade ice cream.

Martha Jane Coleman Banks, born in 1833, was expected to make and preserve most of her family’s food. The recipes in her commonplace book, including those cut and pasted from newspapers, show a much more rural, self-reliant way of cooking. There are instructions for a quick method of churning butter, canning tomatoes, and drying peaches.

We also get a sense of the domestic appliances at Banks’ disposal in these recipes, especially since the butter article notes the ‘new’ way of boiling milk in a kettle. The book also illustrates the initial growth of mass production, as the author of one newspaper article recommends that women keep canned food in Northern-produced tin cans, which “cost only 12 ½ cents each” and will keep for decades if washed properly.

A large issue for a housewife of Banks’ time was the problem of refrigeration. While artificial refrigeration had been invented in the 18th century, refrigerators for the home were not invented and mass produced until 1913. The recipes in Banks’ commonplace book offer a keen reminder of this fact, as one advises that a can of vegetables not contain “more than can be consumed at two meals in warm weather, as the tomatoes soon spoil after the cans are opened.”

However, Banks’ time period was also rife with new produce, as America saw the mingling of English, Native American, and continental European peoples and crops. One regular feature in a newspaper Banks read was the “Horticultural Department,” which offered expert advice on how to plant and prepare produce. An article from 1854 taught women how to cook asparagus, which the author noted was “not yet appreciated in the up-country of the South.” Other vegetable recipes in this article included ones for beets, cabbage, carrots, cucumbers (apparently fried cucumber is delicious), “Indian corn,” “spinage,” and salsify (a root vegetable similar to parsnips). The instructions for cooking these vegetables were almost always to boil them and then smother them in butter.

By the time that Annie Perkins was compiling her commonplace book in the first two decades of the 20th century, the landscape of American cooking had changed dramatically. Perkins’ book features a majority of dessert recipes, including ones for basic pound and sponge cakes as well as more exotic ingredients such as cantaloupe, coconut, and chocolate. Compared to Banks’ time, Perkins would have been expected to purchase many more of her goods, perhaps freeing up time to create more lavish and complicated desserts. However, most of the recipes were more basic ones that a young housewife would have been expected to master.

Perkins’ commonplace book also has a greater variety of ingredients than does Banks’, especially in regards to meat and fish. Banks’ book offers few meat and fish recipes, and those that exist tend to be of animals a rural Southern woman would have access to, such as chickens and pigs. By contrast, Perkins’ recipes include ones for anchovies, clams, canned salmon, and oysters. Not knowing exactly where these two women lived, it is possible that Perkins had more access to fish because she may have lived on a coast. However, the existence of canned fish in her recipes also suggests that by her time mass production allowed for more variety in the diet.

Lastly, we can also get a sense of what appliances Perkins’ kitchen had from her commonplace book recipes. One recipe for cheese puffs requires the use of a grater, a saucepan, paper cases (similar to muffin cups), and an oven, which is a lot of work and appliances for a so-called first course at a dinner party. An article elucidating the best way to make toast scoffs at the idea of using an older toast rack, saying that it “allow[s] the heat to escape, and [is not] recommended.” Perhaps most in contrast to Banks’ difficulties with refrigeration, Perkins’ commonplace book includes handwritten recipe for homemade ice cream, calling attention to the fact that refrigeration and packaged ice were available by the early 20th century.

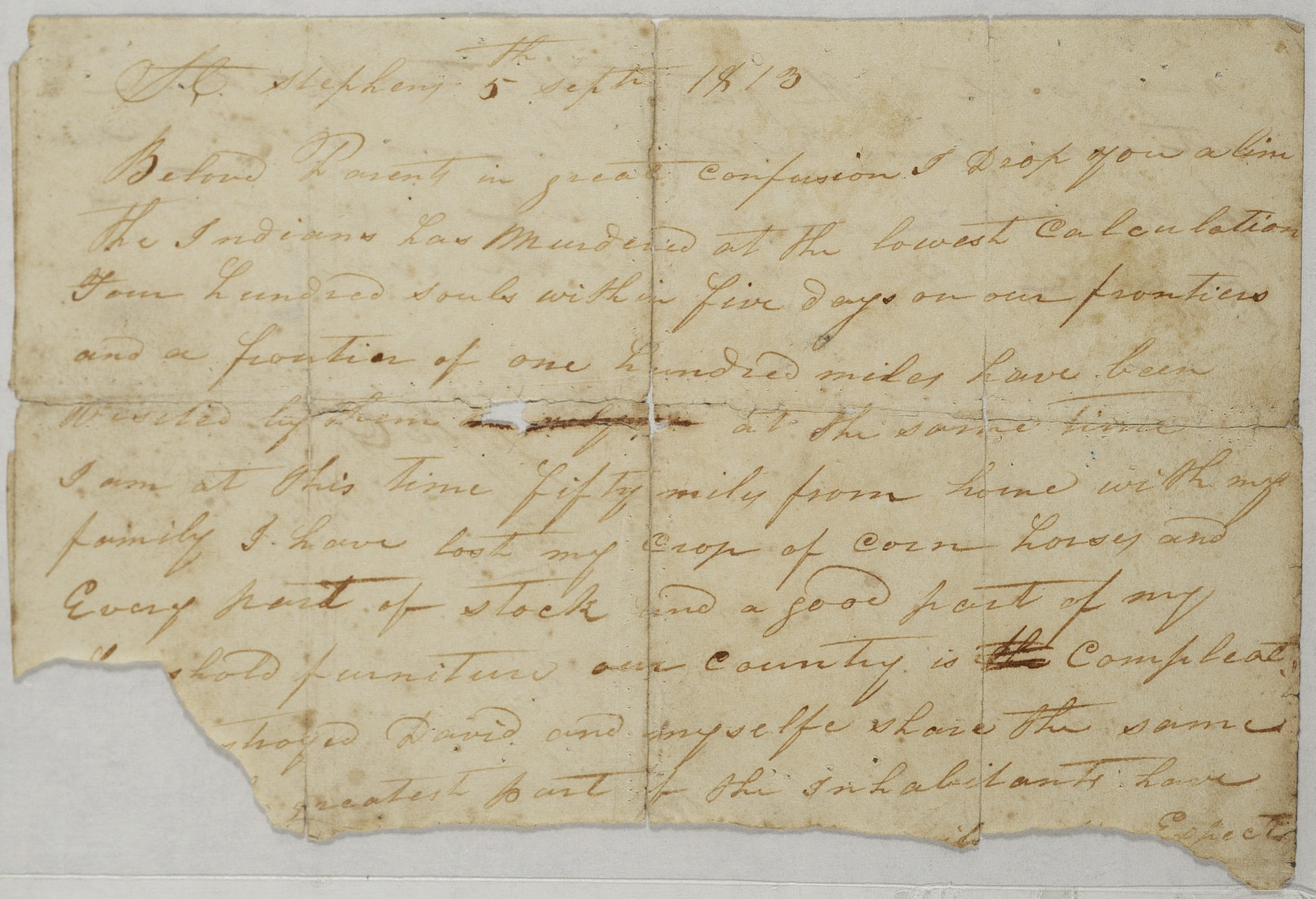

According to the

According to the  an early 20th century

an early 20th century